In my concept of running efficiency, the stride has two halves:

In my concept of running efficiency, the stride has two halves:

- Hip flexion – upward, forward lifting of the leg; and

- Hip extension – rearward, downward pushing off of the leg.

Over the years, I seem to have placed more value on hip extension than hip flexion. The reasons for this have varied and have included focusing on the importance of “strong glutes” and flexibility into hip extension, as well as the simple notion that running is a gravity-dependent activity and pushing off the ground is arguably the key propellant of forward running.

As such, by greatly emphasizing hip-extension strength, range of motion, and efficiency, hip flexion dropped to my professional wayside. Not anymore! In fact, I have come to the realization that hip flexion is not only an equal half of the yin and yang of the running stride, but–when executed with strength and efficiency–it accentuates everything and is a key to super efficient, fast, and strong running.

In the rest of this article, I outline three key benefits of maximizing hip flexion, what happens when the running stride lacks efficient hip flexion, and a four-exercise progression to improving hip-flexion strength and efficiency.

Three Benefits of Efficient Hip Flexion

These are the three key benefits of efficient hip flexion.

1. Efficient Landing

In treating injured runners, what is most obvious to me is the optimization of landing efficiency, namely by avoiding over-striding. As we’ve previously discussed, an over-stride landing–which occurs when any part of the foot lands significantly in front of the body’s center of mass–leads to increase energy absorbed by the leg and trunk. It also creates both compressive and shear forces at the foot and is a leading issue for trail running and ultrarunning foot problems.

A major factor in over-striding is insufficient hip flexion. After pushing off, hip flexors will lift the trailing leg forward and upward. This upward-forward motion then results in a straight-downward landing of the foot. This compact up-down action results in a foot strike more beneath our body, with less braking forces applied. And while a pawback focus can help prevent an overreaching foot, strong, efficient hip flexion is required for a true up-and-down leg action and under-body foot strike.

2. Reciprocal Strength

Newton’s Third Law of Motion states that “for every action there is an equal and opposite reaction.” Stronger hip flexion invariably adds both range of motion and strength to hip extension. Thus, the stronger we use our hip flexors, the stronger our glutes get, too! This phenomenon is on full display amongst our greatest and most efficient stars in trail running and ultrarunning.

3. Joint Efficiency: Lock and Load the Glutes!

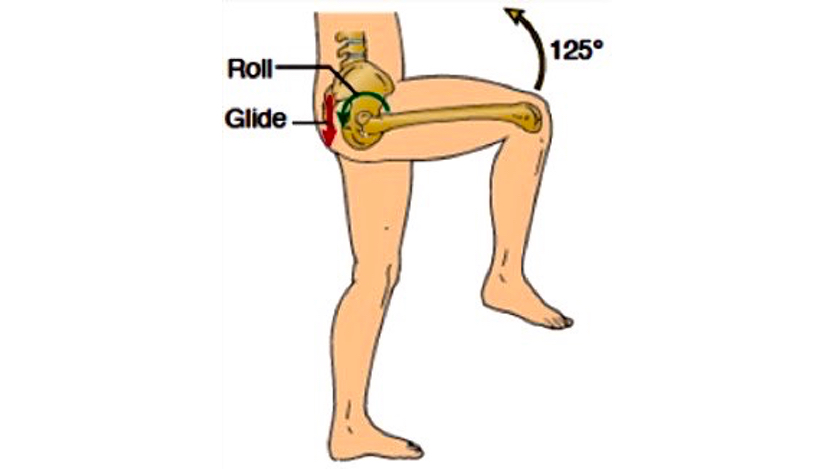

This third concept is more elusive, but gets to the heart of peak efficient hip-joint function. The hip joint is a “ball-in-socket” joint. The femur has a ball-shaped end that fits within the saucer-shaped socket of the pelvis. When we efficiently flex and extend the hip while running, that ball makes slight movements–slides, glides, and spins–to stay centered in the socket. These small movements are called arthrokinematics. With a running hip, the ball of the femur moves on a mostly stable pelvis. In this instance, the arthrokinematics are opposite: when the femur bone flexes (lifts upward), the ball must slide and spin downward to stay efficiently centered in the socket.

This movement is vitally important for two reasons. First, efficient position and motion of the ball-in-socket joint is key for injury prevention. Inefficient position and motion can cause impingement, or a pinching-like stress on the ball in the socket or the muscles that act on the hip. This can potentially damage aspects of the hip joint, including the hip labrum, which is a connective tissue o-ring that helps keep the ball centered in the socket.

Second, and more importantly, this ball-in-socket position affects efficient muscle firing. For muscles to properly act on the hip joint, the ball of femur bone needs to be maintained in a neutral position in the socket throughout all of its motions, including in flexion and extension while running.

The yellow, 125-degree arrow indicates the upward flexion of the hip. The green “Roll” and Red “Glide” represent the athrokinematic motions that counterbalance the movement and keep the ball centered in the socket. Image: O.quizlet.com/4tCgcJ7WMJJq6sbPDm58HQ.png

What Happens When the Running Stride Lacks Efficient Hip Flexion

But what if the running stride lacks efficient hip flexion? Such a deficit may cause a muscle imbalance or inefficiency of ball control in the socket. Without an equal forward and rearward pull, the hip ball may not slide or glide efficiently and instead migrate outside the midline position.

A ball that isn’t balanced in the center of the joint represents a mal-aligned joint. Impaired alignment can make the joint seem or truly become stiff, taking more strength and energy to move. Worse, a mal-aligned joint can impair the nervous system’s ability to “activate” muscles to move it.

This is a critical factor in glute-muscle activation, the ability for an athlete’s brain to find and turn on the glutes to efficiently move the hip. This is a huge clinical challenge for many sports-medicine professionals who struggle to successfully achieve glute firing for ailing runners. But effective glute firing isn’t simply about strength. It’s also about efficiency. It begins with the hip joint properly positioned, in order for those muscles to properly pull.

Hip-Flexion Exercise Progression

Now we understand that hip flexion isn’t just about a big, powerful stride that only the elite runners need for running fast. Hip flexion is a key component for healthy, balanced, and efficient running. And it just may be your missing link to your best running. Here’s how we improve it.

Prerequisite Mobility

In order to work on hip-flexion strength, we need a baseline level of hip-flexion mobility. The first step is self-assessment. If you cannot get your thigh to your ribcage (or close to it) with the opposite leg straight, then hip-flexion mobility work needs to be done. If your restriction is stubborn, consider trying the side doors of rotation and abduction. Once you have the flexibility, it’s time to strengthen.

The two keys for efficient, running-specific hip-flexor strengthening are:

- Maintaining neutral (slightly arched) spine by not flexing the trunk; and

- Maintaining pelvic level by flexing the thigh upward without hiking the pelvis.

Here is an exercise progression that works on the hip flexors from the floor to standing. Each exercise can be done with or without a resistance band.

Bent-Knee Abdominal March

This basic exercise works on full hip flexion, counterbalanced by a hip-extension push-off with the opposite leg.

Target – Flex and hold the upward position for one full second, then slowly scissor the legs without motion in the spine. Perform 10 to 20 (or more) repetitions per side, or until fatigue.

Running Bike Pedal

This progression works the hip flexors with more range of motion, this time countered by a straight leg.

Target – Flex the thigh upward against a straight opposite leg. Slow alternating motions can be done, or the repetitive pulsing of hip flexion in the end range. Perform 10 to 20 total repetitions per side, or until fatigue.

Plank Hip Flexion

This is the most difficult but most important strengthening position for the hip flexors.

Target – Find and lock into a neutral spine before assuming the plank position. Flex the knee upward without flexing the spine and maintain neutral. Perform 5 to 10 repetitions per side with a 5- to 10-second hold, or until fatigue. Namely, that fatigue will be your inability to keep your spine in a neutral position.

Standing Hip March

This is more running specific, but arguably easier without the core challenge of a plank from the previous exercise.

Target – Achieve full hip flexion on a neutral, stable trunk and neutral pelvis where the pelvis doesn’t hike up on the flexed side. Perform 5 to 10 repetitions per side with or without a hold, or until fatigue.

Final Thoughts

Strong and efficient hip flexion isn’t just for fast runners! It can help us all run faster, farther, and with less potential for aches, pains, and injury.

Call for Comments

- How’s your hip flexion? Did you pass the mobility test or do you need to gain some mobility?

- How do these exercises feel? Which of them are more difficult and which feel easier?

- Is there any challenge in maintaining a neutral spine and in keeping the pelvis level while doing these exercises?