From the sidewalks to the trails, runner and wellness changemaker Alison Mariella Désir, 35, has spearheaded multiple organizations and political campaigns to uplift thousands of runners and their health security. Throughout her career, she’s advocated for mental healthcare and organized social-political movements to support womxn, Black Americans, and diversity in running nationwide. She’s been recognized for her work with several accolades including in The Root 100 as one of the most influential African Americans between the ages of 25 and 45. Women’s Running also celebrated her as one of 20 women who are evolving the sport.

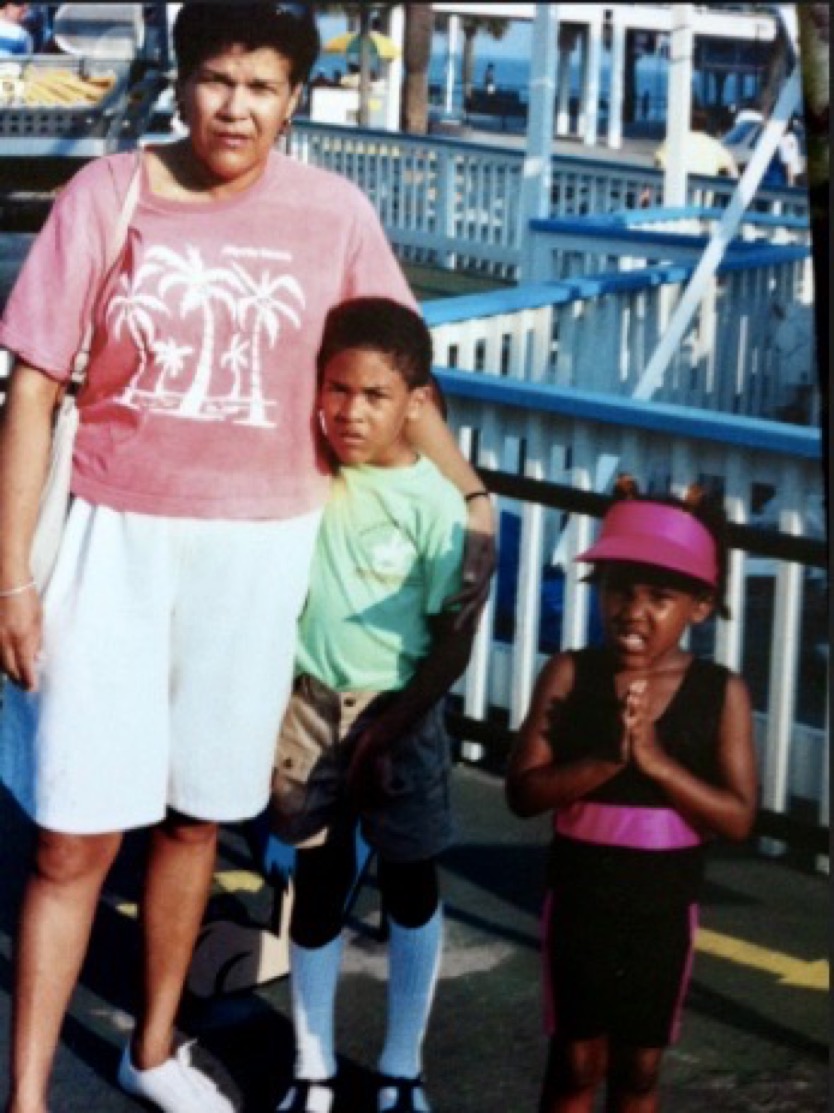

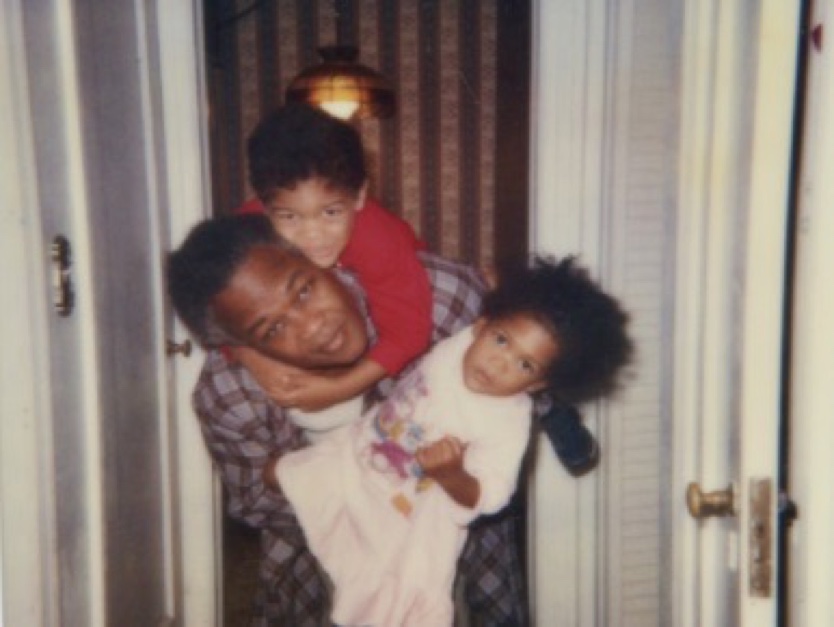

Désir was born in Harlem, a district of New York City in northern Manhattan, in 1985. Her mother emigrated from Colombia at 14 years old. Her father grew up in Haiti and moved to Harlem at age 27. She was raised with her brother in a New Jersey suburb, where she attended grade school. Her earliest running memory involved racing boys on the playground at recess: she was a natural sprinter.

In the sixth grade, she was enrolled in private school and formally introduced to running as a sport. She joined the track-and-field team, where she competed in the 100-meter dash and 80-meter hurdles. With early talent and drive, she qualified for the Junior Olympic Games in the 80-meter hurdles. In high school, she focused on the 400-meter dash and 400-meter hurdles. “Growing up, I was nicknamed ‘powdered feet’ by my father, because of all the different activities I took on and enjoyed. It’s a Haitian Creole saying that describes someone so active that you never see them—just the footprints of where they’ve been in powder. My father also wondered if this might manifest as an inability to focus or to have self-destructive tendencies, because I could never sit still,” says Désir. Beyond running, she was academically successful and involved in soccer, music, and the arts. Her parents encouraged her goals and pursuits. She says, “My parents, who were immigrants, wanted to make sure that my brother and I had everything that they didn’t.”

Désir’s diligent work led her on an early track to graduate from high school and she was accepted into Columbia University, in New York City. In 2007, she finished her bachelor’s degree in history. Three years later, she returned to Columbia University to pursue her first master’s degree in Latin American and Caribbean studies, which she finished in 2011. After graduation, the 27-year-old hit a deep depression as her whole family struggled. Her father was diagnosed with Lewy body dementia. She and her mother became part-time caregivers and watched his decline. She couldn’t find a job. She experienced a mental-health emergency in that she was suicidal and overdosing on pills.

But on social media, she noticed a friend of hers training for a marathon. He finished the race, which proved to be an amazing experience for him—and that stuck out to her. Her Black, average-sized friend was not the popularized marathoner archetype. “Still today, the mainstream image of marathon runners is skinny white guys. The year after my friend ran, I signed up for Team In Training, the fundraising arm of the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society, to raise money for the organization in exchange for a spot in the 2012 San Diego Rock ’n’ Roll Marathon,” she says. Prior to that debut marathon, Désir had worked for multiple nonprofit organizations but hadn’t been specifically involved with fundraising. The combination of a running experience—including the personal and communal health benefits—and leveraging the sport to support a larger cause would become a theme within Désir’s lifework moving forward.

Her marathon experience catalyzed her creation of Harlem Run, a Harlem-based running group, in 2013. In the bustling city, Harlem Run organizes inclusive weekly meetups for urban runners of all backgrounds, abilities, sizes, ages, and styles including runners and walkers. In essence, Harlem Run fosters a welcoming space for runners to connect. “My experience of running the marathon, in 2012, and finding community after being isolated for so long transformed my life. Initially I thought I’d run this marathon and be done with running. But of course I got hooked. After crossing the finish line, it dawned on me that there were not many people of color with whom I was training and running. This was such a great gift that I’d discovered that I wanted to share with my own community,” she says.

At the beginning, Harlem Run was a labor of love. She showed up every Monday and usually ran alone. “Back then, there wasn’t as much interest or excitement, or as many clubs and crews, around running,” she says. Slowly, more runners poured into the fold. She identified and connected with other run leaders in the community. One-and-a-half years later, groups of 100 to 150 runners filed into each weekly gathering. “Whether you’re a walker or a six-minute-mile-pace runner, you can show up and find someone you stick with,” she says. Today, close to 300 runners show up at the summer gatherings and around 75 runners meet during wintertime conditions. “It’s a way to stay in touch in a city that is really isolating. For many people, their schedule is: you go to work, get a drink, and go home, so this is one of the few social places,” she explains.

A year after founding Harlem Run, Désir returned to Columbia University, in 2014. She completed her second master’s degree in counseling psychology, in 2016, followed by a third master’s in 2018, in education. Her personal transformation from running inspired her schooling. “When I started running, I felt better about myself and I pushed myself. I wanted to know the connection between running and mental health. I wanted to know what I was experiencing. I found a counseling-psychology program at Teachers College, Columbia University, which is a graduate school for education, health, and psychology. I liked that the program is grounded in a social-justice approach, and it introduced me to theoretical frameworks that are not discussed in traditional counseling programs including feminist and multiculural frameworks which look at how identity—race, gender, sexuality, etceteras—and social factors impact your mental health,” she says.

In the middle of those two master’s degrees, she founded a second huge initiative: Run 4 All Women, an organization that combines grassroots activism and fitness empowerment to make a positive impact on women and communities. In January of 2017, the organization kicked off with Désir and three other women running a 240-mile relay from Harlem to the Women’s March in Washington, D.C. Their effort drew attention and fundraised $101,525—more than double their goal of $45,000—in 20 days for women’s health rights and Planned Parenthood. More than 1,000 other runners showed up in support and solidarity along the way.

“After the 2016 presidential election, I thought about how big my platform was becoming, and how many people I could reach, and felt that despite the platform and community, I hadn’t done enough around the election. If more people my age and in Generation Z had done more, the outcome would have been different. We assumed that [Donald] Trump could never be President,” she says. She decided it wasn’t too late to organize a meaningful movement. “The idea was to run in support of the Women’s March and fundraise for Planned Parenthood. At that point, President Trump was already targeting women’s bodies and reproductive health. This run was such a good way to show the power of our bodies and the power of movement while fundraising,” she says. But the initial idea she had to run with a few friends during the day, crash on couches at night, and fundraise $45,000 took a whole new energy.

With her parents when graduating from Columbia University with her first master’s degree in Latin American and Caribbean studies.

“My mom gave $400—I thought it was the biggest donation we were going to get. But over the course of few days, it went viral. Women across the country reached out to ask how they could get involved, whether they were showing up for the run or contributing in some way. We converted it to an overnight relay. Over the course of 60 hours, more than 1,000 runners showed up. Anyone could sign up in four-mile increments to run with us. There’d be cheer stations. One group of women had oranges. Kids had signs. People met us at 3 a.m. with coffee. It was incredible the amount of support. What stood out to me was how important it is to have alternative ways to engage in the political process. Not everyone is going to run for office or protest, but running can be a form of political engagement. After completing that relay with the energy of using running for social change, people wanted to know more, and we thought there was an opportunity to share our knowledge and build community around this idea of moving your body and doing it for a powerful reason,” she explains.

Post-launch, Run 4 All Women created a brand-ambassador team, organized a national summit, and hosted state chapter events. They fundraised another $50,000 for Planned Parenthood. In 2018, they organized a grassroots campaign called the Midterm Run, to support progressive candidates in certain states. The goal was to educate and inspire communities to engage in voter-registration drives, participate in community runs, and talk about voting. That September, they hosted a week-long series of events to motivate people to vote. Their efforts have continued.

Also in 2016, Désir experienced trail running for the first time. “Trail running was so foreign to me. The first time I was introduced to trail running was through Under Armour,” says Désir, a former sponsored athlete for the brand. “They took a bunch of run-community leaders from cities including New York City to Colorado for a retreat and race at Red Rocks,” which she ran with a gleaming smile on her face despite the quick foray into higher altitude. “From then on, I realized that I loved trail running—it was so different from running on roads, and I’ve run several trail events since,” she says.

Among those trail events, The North Face Endurance Challenge Series – New York at Bear Mountain State Park was especially memorable. She ran the marathon relay, and she couldn’t believe how close the rugged mountains were to Manhattan, just a one-hour drive north. “I spent all my life right there and never knew how close access was to those trails. So many people in New York don’t leave their block. People can grow up here in one borough and never visit another. They’re constrained to what’s around them, due to lack of resources and exposure. Bear Mountain is so close to New York City and, in theory, accessible. It’s beautiful and the trails are difficult,” she says.

Today, Désir is a Global Athlete Ambassador for Hoka One One and an Athlete Advisor for Oiselle. She’s also a USA Track & Field Level 1 certified coach and Road Runners Club of America certified coach. She’s a writer and author. She recently published an essay, “Ahmaud Arbery and Whiteness in the Running World,” on Outside, and she wrote the forward for Running is My Therapy: Relieve Stress and Anxiety, Fight Depression, Ditch Bad Habits, and Live Happier, by New York Times best-selling author Scott Douglas. She’s taken a step back from her direct role as a counselor to spend time on broader community-wellness initiatives. And, in the past year, her running evolved as she became a mother.

Désir’s firstborn, Kouri Henri Figueroa, is now a year old. Désir has been transparent about how giving birth and early motherhood have been hard on her mental health. At 36 weeks pregnant, she went to the doctor who found that she was five centimeters dilated, had preeclampsia, and needed an emergency c-section. “The whole experience of giving birth was traumatic mentally and physically. I’d heard so much about the mortality rates among Black women, and I was convinced that I wasn’t going to make it out after giving birth—thankfully I did. Then, I didn’t have a clear understanding of what the recovery and postpartum period would look like. I thought I’d be back to running in three months. I was cleared to run after six weeks, but I didn’t have motivation or interest to run until six months later. Then, I was navigating being tired and what the baby needs. I had postpartum depression and anxiety. It’s been a really tough year,” she says.

To help others, she shared her personal experience in a Shape video, recorded last October. “When you share your struggle, it allows others to be vulnerable also. Most of us feel we are the only one with these struggles. I find that the more I’m open about my struggles, the more I realize other people are dealing with similar things. There’s so much healing with sharing and talking. It was helpful for me to share my story, and in turn helpful for women who could put a name on what they were going through,” she says. Recently, she’s felt progress. In the past three months, she’s consistently been able to get out the door. Three to four times a week she runs or walks with Kouri in the jogging stroller.

For the 2020 campaign run, Run 4 All Women partnered with Oiselle to create a virtual relay called Womxn Run the Vote: To Benefit Black Voters Matter. The event is from Atlanta, Georgia to Washington, D.C., on September 21 to 27. Teams of 15 to 20 will virtually run the 680-mile journey while learning about civil-rights historic sites and individuals. The effort will raise funds for Black Voters Matter, an organization dedicated to increasing power in marginalized, predominantly Black communities. To date, Womxn Run the Vote has raised $200,000. The virtual event will use an interactive app called Racery that allows runners to log miles, move across the map, and read educational pinpoints as they make their way.

Désir entrepreneurism hasn’t slowed. The day Kouri was born, on July 23, 2019, she had an idea for her newest venture. Enter the Global Womxn Run Collective, an organization that connects and empowers womxn leaders in the running community. The concept was inspired after “being in industry for seven years and recognizing the disparity in terms of who had the most power.”

“The male-led running groups were getting the most access to resources. They were always organizing events and leaving women out of the conversation. They seem to have more direct contact with brands. And when you look at the running industry in general, whether it’s the Running Event trade show or running-industry conferences, it’s largely white men in attendance, despite that fact that women make up the highest participation rates at endurance events. Despite that, I knew a lot of women leaders, so why not organize on our own? Why not create resources for each other and at the very least let each other know we exist, so that we can share best practices and have conversations outside of this male system. It’s a space that’s not about brands. Whoever you are, come to the table.”

The organization is developing a directory of worldwide running crews and groups with womxn founders. They are also planning virtual workshops for New York City Marathon week in November. Offline, they organize conversations among womxn crew and club leaders around expectations of brands, how to organize during COVID-19, and other topics. “We hope to allow for a space of new womxn leaders,” says Désir.

This May, she also launched the 2020 Meaning Thru Movement Tour, which is a culmination of her training in mental-health counseling, years in the running industry, and wanting to bridge the two. Pre-COVID-19, it was supposed to be a six-city in-person tour. Instead, it evolved into a nine-event virtual tour. “It’s been more impactful, because more people could be involved,” she says. The tour, which concludes on September 26, has featured conversations with mental-health professionals on topics like intergenerational trauma, allyship, and self-compassion; conversations with community organizers and activists; and a movement component like a 5k or yoga. “The goal is to bring to the table the difficult conversations that we don’t often talk about, because we tend to think of running as this space that’s completely separate from the real world. When you run you’re free and unencumbered when in reality many people run because of these mental-health issues. Or, they run and are still obviously impacted by things that are going on in the world. The hope was to bridge those connections,” Désir says.

More than 600 people registered for one of the tour’s events, a discussion with Dr. Robin DiAngelo, the author of White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk About Racism. “That conversation came out of the op-ed piece I did for Outside, where I called out the industry, and talked about how racism and white supremacy are embedded in the industry. After writing the piece, I asked Dr. Robin DiAngelo to be a part of the series, so that she could contextualize how racism and white supremacy exist in all places,” she says. Désir also contributed to an NPR film, “How Running’s White Origin Led to the Dangers of ‘Running While Black.’” As the film explains, running became inextricably coded as white in the United States during the 1970s and ‘80s, despite the fact that Black Americans were involved with the activity. She shared more of her perspective about the running industry and racism:

“What is happening in the running industry and in this country and globally is a parallel process. In the United States, there’s finally a reckoning with racism and the ways all of our institutions and ways of knowing are rooted in whiteness. That means there are disparities in terms of health and education. At the same time, in the running and outdoor industries, we’re being forced to look at the ways in which racism is embedded in the industry. All the retail owners and industry conferences are or are led by white men; magazine covers and stories feature white people; board members and brand CEOs are white male. These are things that I and people of color knew, and that’s part of the reason for me creating spaces for people who look like me—but the industry is having an awakening. Black, indigenous, and people of color are demanding more from folks and saying enough is enough. The outdoor industry is a few years ahead of the running industry in terms of the CEO pledge and the work of Teresa Baker, but we’re finally reckoning with white supremacy.”

The Outdoor CEO Diversity Pledge, founded by Teresa Baker in January of 2018, is the first pledge to address diversity, equity, and inclusion in the outdoor industry. When brands join the commitment, they’re connected with inclusion advocates with the goal to advance representation of people of color company wide. To date, close to 180 companies, clubs, and nonprofit organizations have joined. A handful of the signed brands dually represent the outdoor and trail running markets—however, not many. Désir raises an important question: Why are more road running and trail running brands not involved with the CEO Diversity Pledge? Does an additional pledge, inspired by and complementary to Baker’s inaugural initiative, need to be launched specifically for running-related brands?

In the trail running and ultrarunning industry, organizations can start with a formal anti-racism training with a focus on anti-blackness and erasure of indigenous and native people from the lands, Désir says. “Everything we do takes place on native land. But in particular, think about how these events and races take place on sacred lands that have been named by the white men who were responsible for the genocide of millions of people.” Secondly, organizations can “hire diverse folks in a way that’s not tokenized. And ensure that they’re entering an organization that’s ready to welcome them, that is committed to diversity and equity,” she adds.

Among race events, it’s important to consider accessibility regarding entry fees, which could be a barrier of entry for marginalized runners. And, if it’s a 24-hour ultramarathon, especially in “Trump country,” how is safety provided for people of color? “Some trail and ultra races are so expensive, or in places that are so exclusive and hard to get to, or frankly, they’re in Trump country. For instance, I won’t go to race in the middle of [a rural U.S. location] if I feel I might be the only Black person there and I’m not going to have any kind of safety,” she explains.

“There are quick fixes—like hiring and trainings—and then there is a long-term strategy that requires an anti-racist perspective to be embedded into the trail running community, which is essentially shifting the current culture,” explains Désir. In order for trail running and ultrarunning events to establish a safe, comfortable environment for Black runners, and inclusivity for people of color, Désir offers the following guidelines:

Leadership: Is everyone involved in organizing the race white? Hire and retain a diverse staff, so that from the very beginning of an event’s conceptualization, diverse perspectives are a part of the conversation and empowered to voice their opinions.

Training: All staff and volunteers must take anti-racist training to help uncover unconscious bias that could negatively impact participant experiences.

Recruiting: How are you recruiting for your races? Is the information only available to certain populations?

Costs: What are the costs associated with the race? Are they cost prohibitive? [For example, multiday ultrarunning events can cost $1,000 to $2,000 for registration alone.] How are you closing the gap?

Location: Where is your race located? If you are hosting races in locations that are known to be racist or have a history of being sundown towns, what effect does that have on your participants? [Editor’s Note: Sundown towns were all-white neighborhoods and municipalities in the U.S. that historically practiced strict racial exclusion against non-whites through violence, force, discrimination, and local laws. Thousands of these communities have existed, and some still persist across the nation.] How can you ensure participant safety? If you can’t, don’t host your race there. Also, staffing police officers for safety at a race event would be terrifying [for Black runners]—particularly in isolated areas!

Land Acknowledgements: Every race should begin with one.

Sponsors, Timing Companies, Vendors, Partners: Recruit from Black-owned and minority-owned businesses; and/or require that anyone you partner with shares your same commitment to anti-racism and has diverse staff. Do not partner with all-white companies.

Representation: Marketing materials and communications should be diverse. Authenticity is key here—not tokenism.

Brand: Make your commitment to anti-racism known in a public declaration. Make those values visible on your website, social media, and communications materials, so that race participants can get a sense of the culture you promote.

On an individual level, a key piece to help in the current civil-rights movement is to cultivate awareness and self-education. Désir says, “If you have lived a segregated experience, think about why that is. Think about who has access to the space you’re in. Think about who is not there and why they’re not there. Then, you can start making demands of the industry. You can call out running magazines about the lack of representation and marketing, and appeal to brands about diversifying boards. It’s important for white people to do that as allies. Black people can’t do this on their own.”