As far back as Navajo (Diné) community leader, coach, and competitive runner Shaun Martin can remember, he and his brothers were woken by his dad at 5 a.m. to run eastward in celebration of the birth of a new day with father the sky, mother the earth, and the holy sun–a traditional Navajo ritual. His dad worked at a coal mine 90 miles away, so he’d drive off 30 minutes later, wave, and signal for the kids to turn around and finish their four-mile run.

“I grew up with the old teachings and actions of our ancestors. A significant part of the Navajo way of life is running. It’s a sacred act. Running is done in various coming-of-age and rite-of-passage ceremonies. Running is built into our creation story: how all people came to be in this world,” says Martin, 38, who also founded the first sanctioned ultramarathon in the Navajo Nation, the 34-mile Canyon de Chelly Ultra, in canyons that have been occupied by indigenous peoples for nearly 5,000 years.

Running is in Martin’s DNA, blood, and ancestry. He was raised as a daily runner in a Navajo home “with a father who didn’t just embrace Navajo culture—it was our way of life,” he says. Martin grew up in LeChee, Arizona, in the northwest shoulder of the Navajo Nation and next to the city of Page, with two exemplary parents, Allen and Lisa Martin, and three older brothers, Donovan and twins Tim and Theo. The Navajo Nation is an indigenous territory located in Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah that spans more than 27,000 square miles. The LeChee community is triangulated by three well-known geographic locations: Antelope Canyon, Lake Powell, and Horseshoe Bend, the latter of which Martin recalls as having no existing trail when he herded livestock there as a kid.

Running embodies four distinct lessons, according to Navajo tradition: to celebrate, pray, learn, and heal. Martin explains, “We run to celebrate all of the positive blessings and hardships we’ve been presented. The act of running in the morning is a prayer, so we yell out loud to pray. Running is a mentor: When we push on and overcome physical obstacles, that translates to other areas of our life to help us become more successful, grounded, and better people. Lastly, running is medicine. It helps us heal and better ourselves in a ceremonial way.”

Shaun Martin racing the Shiprock Marathon, the only road marathon in the Navajo Nation. Martin has won the race five times. All photos courtesy of Shaun Martin unless otherwise noted.

Tradition Meets Competition

Aside from running as a Navajo tradition, at age four, Martin also learned about its competitive side, which forever influenced his life. It was the U.S.’s Memorial Day, and the neighboring town of Page was hosting a five-kilometer race. Instead of waking the boys at sunrise, Martin’s dad thought it’d be fun for them to participate in the event.

Martin recalls, “My dad is 6’3” and he said, ‘Don’t walk and don’t be last.’ My brothers and I took off. My bib took up my whole torso. Toward the end, my mom said, ‘You haven’t stopped running and you’re doing great. But you better pick it up, because that old lady behind you is catching up.’ I raced the old lady to the end, and I beat her.” Martin received the youngest-runner award that day. “I was hooked. I wanted to run every morning for all of the traditional reasons but also wanted to race to win things,” he says.

To his joy, Martin’s dad entered he and his brothers into more local 5k and 10k races. Next, his parents organized a team via USA Amateur Athletic Union Track and Field, called the Northern Arizona Rez Runners, that was comprised of Navajo kids with running talent in northern Arizona. Many of the team members were childhood friends who were emotionally and physically supported by his family.

“Growing up on the reservation, my brothers and I had a lot of friends who were from broken homes or who lived with their auntie or grandma. We were the exception with both parents at home. They didn’t abuse substances and they both worked. Our friends often stayed with us. My parents raised my friends the same way they raised me. If I had trash to pick up, livestock to herd, or wood to chop, our friends were expected to help. And they were expected to run with me,” Martin says.

The kids would all pile into his parents’ Chevy van and road trip to races. Over the years, a number of individuals and one of the age-group teams qualified for the USATF Junior Olympic National Championships, and the latter won a national title in Reno, Nevada. Beyond that team, Martin ran track and cross country, and won many state titles as a middle and high schooler. Later, his brothers Tim and Theo became Division I All-Americans in cross country at Northern Arizona University (NAU) in Flagstaff, where he, too, was recruited to run from 1999 to 2004. In addition to his running career, Martin had always wanted to be a teacher and coach. He’d known since the sixth grade that he would pursue a collegiate career at NAU, due to the school’s outstanding teacher-education program.

Running Leads to Love

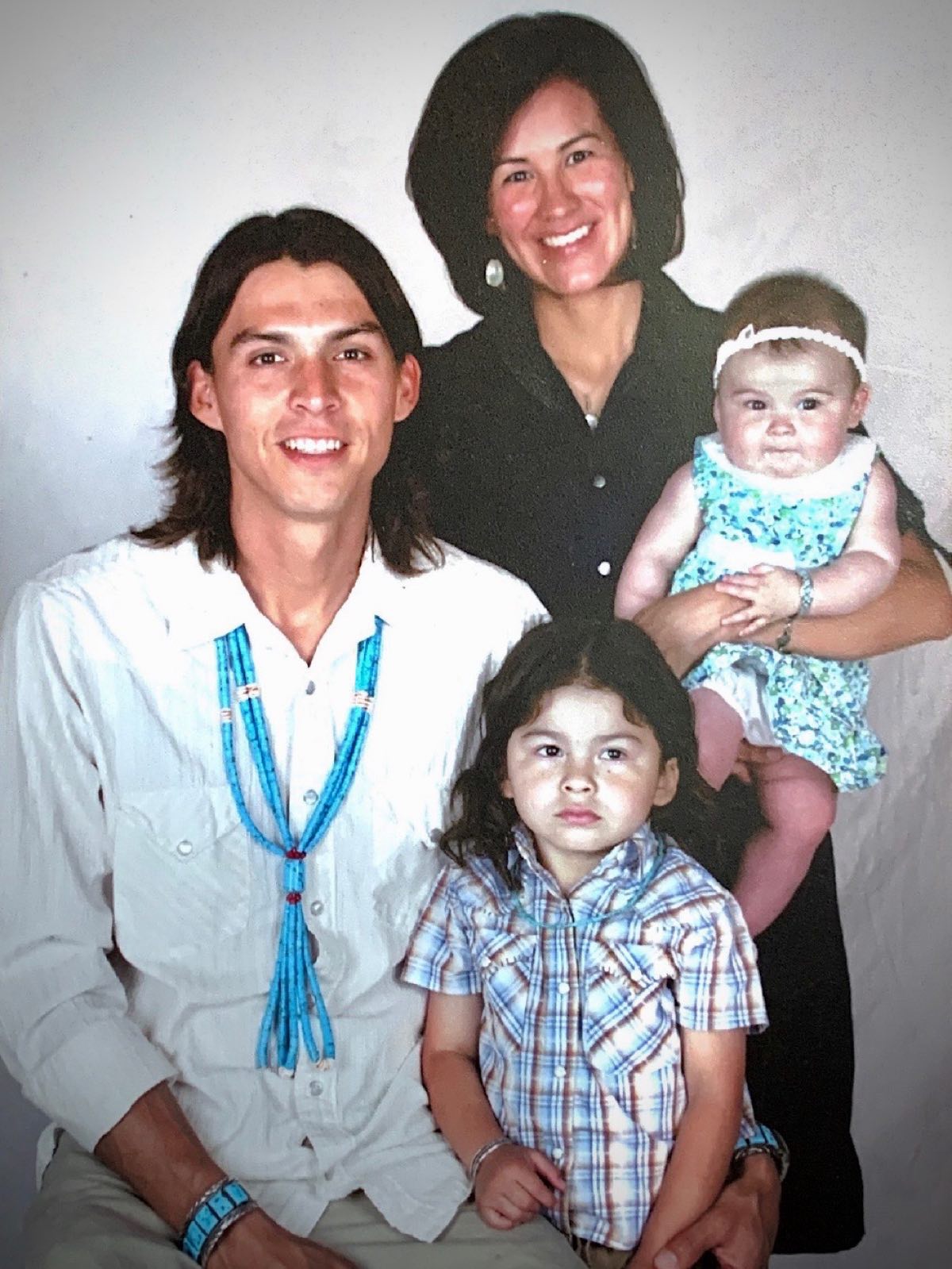

Halfway through college, Martin was riding his bike through campus when a woman stepped into the bike lane. He almost ran her over, skidded to a stop, and exclaimed, “Hey, I know you!” The woman was Melissa Yazzie, a Navajo (Diné) girl he’d grown up with who was also a standout runner. As kids, he ran for Page Middle School and she ran for Chinle Junior High School. They’d see each other at weekend race events, say hi, and chat. They became friends but a special chemistry also existed between them throughout their teen years. After high school, Melissa studied at a junior college and then earned her associate degree at Diné College on the Navajo Nation before enrolling at NAU for a bachelor degree in education. Ergo, Martin was surprised to stumble into her—and was smitten. “It was over. That was it. I asked her out on a date, and we’ve been inseparable ever since,” he says, regarding his now-wife, partner, and mother of their two kids, Maverick, 11, and Isabell, 9.

Though he was falling in love, crisis struck during Martin’s senior year at NAU. He was sidelined with iliotibial band syndrome, an overuse injury. He could hardly walk and couldn’t compete. He couldn’t run for the last three months of his final semester and hobbled across the stage during the graduation ceremony. His identity was shaken. “I struggled. I couldn’t run every morning and race on the weekends. I didn’t know how to define myself if I couldn’t run or race,” he says.

Upon college graduation, Melissa scored a teaching position at an elementary school in her hometown of Chinle, in the center of Navajo Nation. Martin applied for three jobs at Chinle High School. He was selected for each one: a teaching position, head cross-country coach, and head track-and-field coach. This opportunity changed his life. He was reintroduced to his life’s focal points.

“As a Division I athlete, it’s all about training every day to beat people in competition. Those five years at NAU I valued. However, I was losing the traditional Navajo reasons to run. Meeting the kids on the team at Chinle and doing short, easy runs with them healed me. Most of our kids here are Navajo. I embraced the two worlds of traditional and competitive running. As I built myself, the team was built, and vice versa,” says Martin, who was an official mentor, in addition to coaching and teaching physical education, strength and conditioning, and health classes.

Ultrarunning: A Foreigner and First-Placer

Martin started to race half marathons followed by the Arizona Rock ’n’ Roll Marathon in downtown Phoenix—which he detested. “At end of that race, I hated running down a concrete road through skyscrapers with a huge band every mile. It was the complete opposite of what I did at home as a child and what I was teaching my students: to connect to the earth and sky and all of the sacred things in-between,” he says.

At the time, his brother Theo was training to run an Olympic Marathon Trials qualifier, and he suggested Martin register with him for the 2008 Red Mountain 50k in Utah, since Martin was already training at that level. At the time, Martin had no idea about the trail and ultra world, didn’t have a GPS running watch, and still doesn’t like using one. The night before the race, Theo bailed, due to a knee twinge. Martin lined up solo.

“I got to the race and felt out of place not knowing anything about ultras or trail racing. I ran in Asics Kayano shoes, running shorts, a singlet, and nothing else. Everyone had hydration packs, handhelds, shorts, fanny packs, gels, and watches. The last race I’d run was a half marathon on a highway. I took off at 5:13 minute-mile pace, and after a bit came back to the first group. These guys were all talking about the training they’re doing. About three miles in, the sun was starting to rise. We started this big climb, and I took off. I could hear the guys behind me on the switchbacks saying, ‘He doesn’t have a handheld or a watch or a headlamp. He’ll come back after 20 miles.’ It made me want to go faster,” says Martin, who ran so fast that he passed the first and second aid stations before volunteers arrived to set up.

“At mile 25, a guy was there with a water cooler hanging off the back of a pick-up truck. I hung my head underneath it and drank as much water as I could. There were no other supplements. I took off for the last six miles and finished in 3:20,” says Martin, who was 25 years old at the time. Melissa met him at the finish line, where the race director was surprised to see him so early. After that, they left to cheer on Martin’s track team at a meet. He got home at 1:30 a.m. the following day.

“When I woke up the next morning, I could barely stand. But a week later, when the soreness wore off, I thought it was the most awesome experience of my running career. I immediately went online to look for another race,” he says.

Martin continued with more podium finishes at the Goblin Valley 50k (three times), Desert Rats Trail Running Festival 50 Mile, XTERRA Estrella Mountain 20k, Red Mountain 50k (again), and Mt. Taylor 50k. He was curious to run even further, so he completed the 150-mile, six-day Desert RATS Kokopelli Trail Stage Race.

All the while and for nine years, he continued to teach and coach in Chinle. During that time in his career, the cross-country and track teams won 14 high-school state titles. “We had 49 kids go to college on scholarships. That’s a big deal for us on the reservation with all of the hardships our kids endure every day, and them using their academic and athletic abilities to go to the next level,” Martin says.

Then, 2012 was a catalyst year. In a career highlight, Martin finished in the top 10 at the stacked The North Face Endurance Challenge 50-Mile Championships. “They said it was the greatest collection of trail guys in the world at that moment for the 50-mile distance. It was humbling to run with them,” says Martin.

That same year, he left Chinle High School for an opportunity at Diné College, where he served as the athletic director and head cross-country coach for two years. He oversaw 45 kids and ensured that they were influenced by athletics and pursued a college degree. By the end of Martin’s second year, in 2014, the women won the United States Collegiate Athletic Association national cross-country title and the men took second place. A total of 16 students earned the association’s All-American status. “It was a phenomenal growth rate and success level,” Martin recalls.

Canyon de Chelly Ultra

Also in 2012, he founded the Canyon de Chelly Ultra, which takes place in canyons considered holy by Navajos for their thousands of years of indigenous history. The canyons are co-managed as Canyon de Chelly National Monument by the Navajo Nation and the U.S. National Park Service and close to 40 Navajo families still reside in them. Because of all this, Martin needed to secure permits with both the Navajo Parks and Recreation Department and the National Park Service for the event’s 150 racers.

Martin also set up a business account for all of the race’s profits, in order to manage and share that fund with those in need throughout Chinle and surrounding communities. For instance, those funds have supported high-school athletes’ attendance of the Down Under Sports competition in Australia. They’ve purchased running shoes for kids at local races and bought uniforms for local club teams. And an older gentleman needed financial support to run the Boston Marathon.

“It’s the fun part to have that race and an ability to put its profits in one account and help individuals as needed. It’s a super-rewarding experience,” says Martin. The race has also hosted book drives, which have amounted to nearly 700 donated books to date for local schools. Each year, Martin’s family, close friends, and neighboring coaches all volunteer to help put on the race. Ultimately, “I started the Canyon de Chelly Ultra to share our culturally significant reasons to run with the world, and it sells out immediately. Our people see how I embrace running in our sacred canyon. To host this successful event is an inspiration for young people here,” he says.

Martin’s idea and inspiration to create a race followed a solo and euphoric run in the canyon. It was mid-July during the monsoon season, which delivers masculine thunderstorms, as well as lighter, feminine rainfall. A soft female rain was falling when Martin spooked a group of wild horses and ran beside the herd and their colt for two miles.

“I lost track of space and time and it was a connectedness with all the holy people. As I ran back to my house, I felt selfish. I only live 1.5 miles from the mouth of the canyon, and I have these experiences as a Navajo runner in this sacred land all the time. My family and high-school kids seldom get to experience them with me. I thought, I should bring a race here to share this experience with runners from all over the world. Then I can use the race’s profits to support the runners here,” he says.

Tremendous Impact on Navajo Youth

In 2014, Martin returned to Chinle High School as its athletic director where he is able to reach and help 1,000 students. He’s now had that administration job for six years. He oversees the athletic education, teachers, and facilities. On a day-to-day basis, he runs each morning, goes to work at 8 a.m., and gets home around 5:30 p.m.—unless there’s a game. Then he’ll get home closer to 11:30 p.m. During the day, he manages the athletic department’s daily operations.

“We’ve had the largest graduating class of Native American students for the last six years—in the nation,” says Martin. His wife is now an academic coach at Chinle Elementary School. On a personal level, he set aside his own races for a bit to focus on completing his master’s degree in education leadership with a goal to become a principal. He finished his degree in December of 2019, and plans to run a 50-mile race in the summer of 2020. His ultimate running goal then will be the 2021 Leadville Trail 100 Mile.

The resounding impact that Martin has had on the rising generation of Navajo youth in his local and surrounding communities cannot be underestimated.

“Living on the reservation, there are few positive role models. Everything I have on this earth is a direct influence of being committed to my goals and dreams, which is something our kids here admire. Being a Navajo man who is passionate about something—for me, that’s education, running, athletics, and family—and pursing excellence in those things has inspired our young men and women at a level that hasn’t happened in our recent history,” says Martin.

The greatest challenges faced today by Navajo youth—and reservations nationwide in the U.S.—are broken homes and economic struggles. While the Navajo Nation is extremely rich in anthropological history and geological formations, its remoteness, aridity, and lack of infrastructure together create significant economic-development challenge.

“A lack of economic opportunities leads to a lack of families staying together, because a parent needs to go on the road to find job. Life on the road isn’t good. Alcohol and drug use goes up. The Navajo Nation is actually dry. Alcohol is prohibited, but it still finds its way. The kids aren’t struggling with alcohol and drugs, but they see it and have to deal with the after effects of the adults. And the likelihood of them repeating it is probably higher than if not seeing it. There are infrastructure issues like lack of water and electricity across the entire tribal nation. There’s a lack of roads. We’ve got one main road through Chinle that’s paved, and one paved road that branches off of it. Everything else is dirt. Besides all of those issues, our people are still dealing with the historical trauma of how the U.S. government hurt Navajo people with the Long Walk,” explains Martin.

The Long Walk was when thousands of Navajos in the U.S. Southwest were forced by the U.S. military to leave their homes. For two years starting in 1864, people were sent for internment at Bosque Redondo, New Mexico. Thousands of deaths resulted from this genocide and ethnic cleansing. Then, despite the U.S. Treaty of 1868 which established the Navajo Nation and some rights for Navajos, the U.S. government forced Navajo children to attend off-reservation boarding schools, a practice that continued for many decades. In the boarding schools, Navajo children were malnourished, poorly educated, and physically abused. They were also stripped of their language, cultural practices, and traditional appearance as the U.S. government sought to control and assimilate Navajo children into the culture of white settlers.

“My dad was taken from his home near the east rim of the Grand Canyon and forced into boarding school. He was beaten for speaking Navajo even though he didn’t yet know English. You can imagine how someone like his father was hesitant to send his child to school. As an educator today and a Navajo person, we still have a hard time developing relationships with the community and parents. But we’re changing that. We’re facing it head on, and we have more Navajo and culture support in our school systems than ever before,” says Martin.

Today, there is a positive resurgence among Navajo to run, which has been reinvigorated by health and wellness needs. Martin explains, “When I was a kid, running was massive—races were all over Navajo land. It died off for 20 years.”

He continues, “The older people who normally hosted these events just stopped hosting them, and I’m not totally sure why. Participation numbers may have dropped as those who are my age and younger didn’t race as much. Was it everyone wanting to ‘be like Mike’ [Michael Jordan]? Maybe younger parents weren’t taking their kids or families to races as much. It may have been an economic issue that kept people from road trips and race-entry fees. It was probably a combination of everything,” says Martin.

“Now, with help of social networking and the internet, races are immediately known and supported, which has only helped ideas of health and wellness on the reservation. And there is also a greater need for running today. I’m a firm believer that change happens when there’s an urgent and compelling reason. Our people’s health has deteriorated in recent years. Hypertension, obesity, alcoholism, and suicide have all grown enormously over the last two decades. With people rediscovering their prayer, traditional reasons to run, and ceremony, it’s helping them do that fourth reason to run: to heal.”

Call for Comments (from Meghan)

- Have you run or raced with Shaun Martin over the years? Can you share a story of doing so?

- Have you raced the Canyon de Chelly Ultra? What was the experience like for you?

- Are you an indigenous runner? Can you share a little about your relationship with running?