I spend a lot of time listening when I am at races, packet pick-ups, trailheads, and group runs. The conversations are always interesting, and I swear I’m not a stalker. Certain tidbits make me perk up, listen in, and take home an idea to read up on later. Some of it turns out to be fact while other is fiction, myth, folklore, and legend. In this month’s ‘Running on Science’ column, we step away from our normal format to bring you a slightly different approach. We dissect four of these tidbits–common things you hear in trail running talk–and decide, are they fact or fiction?

Fact or Fiction? “I’ll lose all my fitness if I take a couple of days off.”

Even if you haven’t heard this one whispered at a group run, you may have thought it. I sure have. I’m good with a rest day because I know that in order to improve the formula is adequate stress plus adequate rest equals adaptation. I’ve written about this general equation before on iRunFar. But what happens when we get injured, our kid is sick, we have a deadline at work, we take a vacation, or the basement floods and we have to take extra time off, such as a few days, a week, or a month?

Resting will not ruin you. Image: Fizzylemonphysiotherapy.co.uk/rest-days-arent-just-about-muscle-recovery/

Adapting to training, or gaining fitness, is similar to any sort of adaptation, such as heat or altitude acclimation. These adaptations are not permanent or unchanging, and detraining is what we call the rate at which we lose our fitness adaptations. So just how quickly does an endurance athlete experience detraining?

I have good news for you: insignificant change is seen in VO2max, a measure of your aerobic capacity and therefore a commonly used performance metric, after 10 days of no exercise (1). Starting then, there seems to be relatively steady loss, although not exactly linear, in aerobic capacity. The most decay seems to come after three to four weeks off, likely due to a decrease in blood plasma volume (which increases with training) leading to decreased cardiac output. After two weeks of no running, the literature indicates we will experience an approximately 6% VO2max decrease, after nine weeks a 19% decrease, and after 11 weeks without training our VO2max can drop by about 25% (1, 2).

Starting at around 14 days of inactivity, we also begin seeing mitochondrial-density and enzyme-activity decline, both of which affect how well our muscles utilize oxygen and metabolize other energy for muscular activity. This is what would cause a decline in our lactate threshold, or the intensity at which we can no longer utilize lactate aerobically and it begins to accumulate.

So at two weeks completely off, a 6% decrease in VO2max and other decreases in aerobic and anaerobic metabolism, including lactate threshold and cardiac drift (or your ability to maintain a specific heart rate at a given speed), is pretty minor from a performance standpoint.

And, I have more good news for you! The literature suggests that after a more significant amount of time off, say three to four weeks, it only takes four to eight weeks of steady training to bounce back to previous fitness levels.

What happens if we scale back our training rather than rest altogether, such as if we run fewer days per week due to a new baby at home or we substitute cross training while nursing an injury? When we do some aerobic activity, detraining slows down. The literature indicates that you can reduce your weekly training frequency by about 30% (without increasing volume) and see no significant decrease in fitness. This means if you run six days a week, you can step back to four days a week with little ill effect during a discrete down period.

Now, a few notes to clear the air. The type of rest we address here does not cover more severe rest, such as medical bed rest or if you have an injury that really minimizes the amount you can move around. This severe rest leads to a much more rapid fitness decline. The literature has shown that for each day an injured endurance cyclist is on bed rest, they lose approximately 1% of their maximum power output (17).

It’s also important to note that a number of the reasons you might take time off can also lead you to feeling poorly… but only temporarily. Travel, altered eating and drinking routines, less sleep, and illness will impact how you feel physically and mentally and may lead you to think you are losing fitness. But the feelings elicited by these scenarios are short-term and should clear up when you return to your normal activity.

Conclusion

Fiction! Be it for your off-season or because of injury, taking time off can be scary. But the science tells us that we will not lose much fitness with a discrete period of time off. With substantial declines in fitness not settling in until after the three-to-four-week mark, you are definitely going to not only survive that vacation but you may come back from your rest even stronger.

Fact or Fiction? “I only need six hours of sleep a night.”

Although many athletes are more likely to brag about how much sleep we get, we also live in an era of busy-ness. Juggling our family, friends, job, and training can cause us to feel like we don’t have enough hours in the day. Often the place that we pull hours from is our precious sleep bank.

I’ve written in detail on sleep before for iRunFar. The health recommendation for normal adults is seven or more hours of sleep in order to maintain your cognitive, physical, and metabolic health (14). This sleep count bumps up for athletes to eight-plus hours of sleep a night in order to avoid injury and give your body extra time for things like tissue repair.

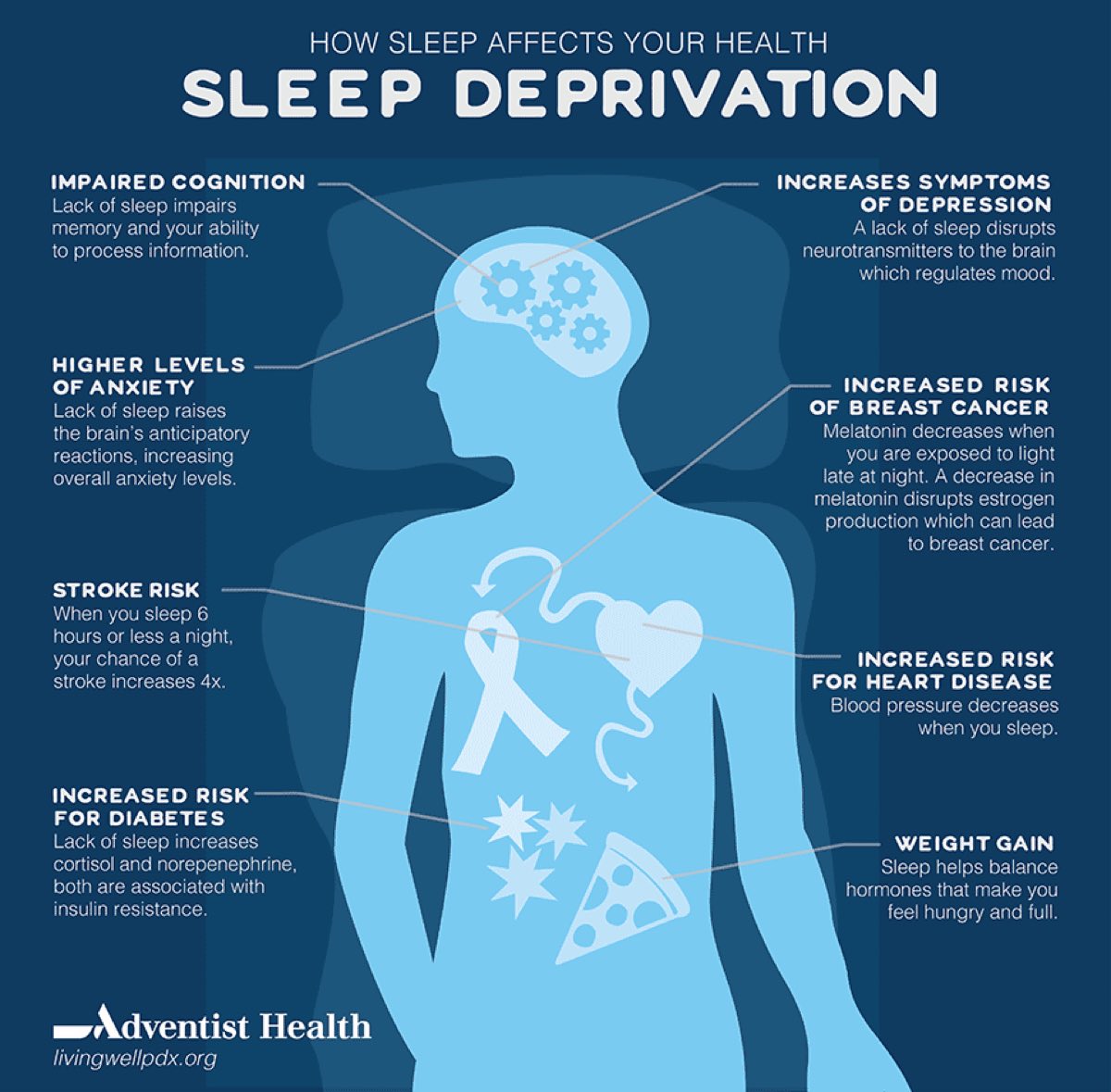

From a health standpoint, we know that even one night of altered sleep, or 2.5 hours less than normal, can cause significant deficits including a decrease in natural killer cell activity (a type of white blood cell responsible for fighting viral infections) and the production of interleukin-6 (IL-6, which is produced by our immune system to help fight inflammation and other infections). Additionally, studies have shown that getting less than eight hours of sleep per night is one of the strongest injury predictors, increasing your odds by 1.7 times (15). Metabolically, sleep deprivation also changes the levels and functionality of the hormones insulin (critical in glucose metabolism), ghrelin (stimulates hunger), and leptin (regulates body weight by inhibiting hunger), which can lead to weight gain or in more extreme cases type 2 diabetes (19).

Finally and perhaps most importantly, sleep deprivation is linked to decreases in cognitive function (hello, slow reaction times) and has even been indicated in an increased risk of developing dementia later in life. Scientists believe that sleep helps prevent degenerative nervous-system and brain diseases by allowing the glymphatic system to do its job. The glymphatic system is the interface between your nervous and lymphatic (responsible for draining lymph from your tissues) systems. Your glymphatic system is most active while you sleep as it picks up metabolic waste and flushes it away from your brain (18).

Now, a couple notes. First, to confirm, we’re referring to chronic sleep loss here, and not the occasional lost night or two of sleep due to a race, travel, or deadline. We all lose sleep sometimes, and that’s okay. The goal is to limit sleep loss as much as possible. And, when you know sleep loss is coming or you’ve had a bad night of sleep, there are scientifically proven tools that can help such as sleep banking (getting successive nights of extra sleep) and napping to help you bridge closer to eight total hours of sleep per day.

Conclusion

Fiction. Can you sleep for only six hours a night? Sure. Should you? Probably not, at least not chronically in order to maintain your performance as an athlete and your health as a human being.

Chronic sleep deprivation leads to poor health. Image: Adventisthealth.org/blog/2015/october/sleep-deprivation-8211-how-sleep-affects-your-he/

Fact or Fiction? “The best cadence to run at is 180 steps per minute.”

I’ve heard it. I’ve been told it. I’ve definitely both worried about it and thought it could be a miracle fix. The idea that there is one ideal cadence for all runners might have been made to stick by the famous running coach Jack Daniels. During the 1984 Los Angeles Olympic Games, he noticed that that from the 800 meters up through the marathon, runners were taking about 180 steps or more per minute. He also noted that when he studied beginner runners throughout his coaching career, they generally ran at only 160 to 170 steps per minute.

Back then, it was believed that a higher cadence was better for two reasons. First, the longer time your foot was on the ground the less ‘free energy’ you would receive from the stretch reflex in your lower-leg tendons, and second, that a slower cadence made for more vertical oscillation (you’re off the ground for longer) and therefore you impacted the ground harder with each stride. Essentially, having a higher cadence should increase your efficiency and reduce your injury risk (6). So what gives? If the best are running at 180 steps per minute, shouldn’t we all be following suit?

It turns out there is a lot of individual and intra-individual variability in cadence. In fact, those same runners Jack Daniels watched at the Los Angeles Olympics ran at lower cadences when they were running slower.

Outside of perhaps height (7), it actually appears that the largest factor impacting cadence is the speed at which you are running. What this means is that as we accelerate, our stride rate (the number of steps we take each minute) increases, more so than the length of each individual stride. This means that I likely have a higher rate of steps per minute at six-minutes-per-mile pace, than I do at eight-minute pace, than I do at 10-minute pace.

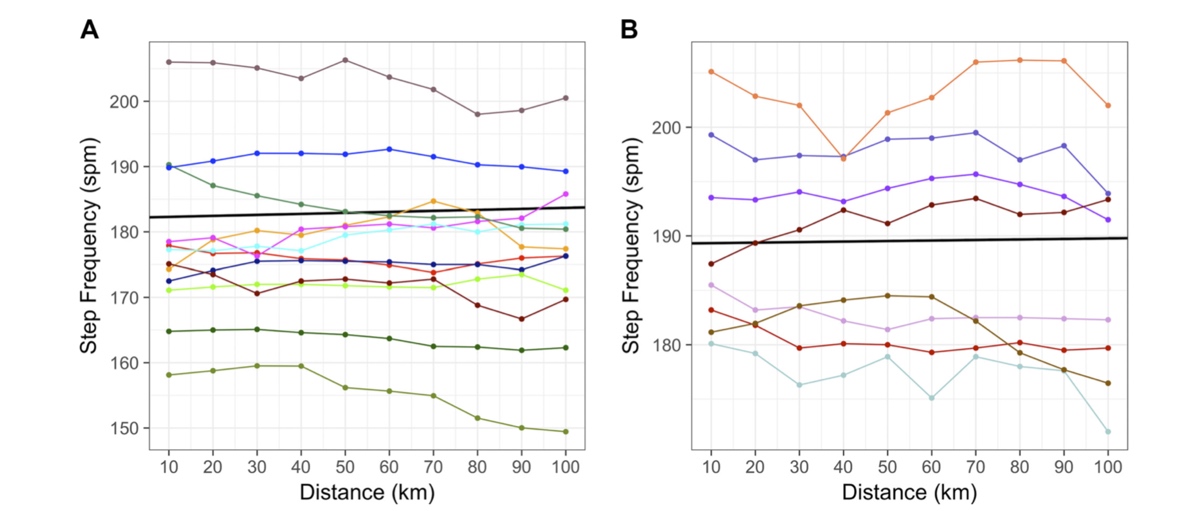

To dig into ultrarunners’ stride rates more specifically, we look at a study conducted during the 2016 IAU 100k World Championships by talented ultrarunner and PhD student in biomechanics Geoff Burns and others which evaluated the cadence of 20 men and women over the course of the event. What Burns and his colleagues found was that although the average cadence of all the participants studied was 182 steps per minute, the variation between runners was quite wide. There were runners who averaged 155 steps per minute and who averaged 203 steps per minute, and still finished within minutes of each other over the 100-kilometer distance (7). So is one runner doing it right?

Running cadence varies significantly among similarly performing athletes at the 100-kilometer distance. The left/A graph shows the average steps per minute at the 2016 IAU 100 World Championships for 11 men, and the right/B graph shows the same for nine women. All athletes finished within the top-25 positions in the race. The runner at the very top of this chart (average 203 steps/minute) and the runner at the bottom of this chart (average 155 steps/minute) finished within minutes of one another. Image: Burns, G. T., Zendler, J. M., & Zernicke, R. F. (2019). Step frequency patterns of elite ultramarathon runners during a 100-km road race. Journal of Applied Physiology, 126(2), 462–468. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00374.2018 (7)

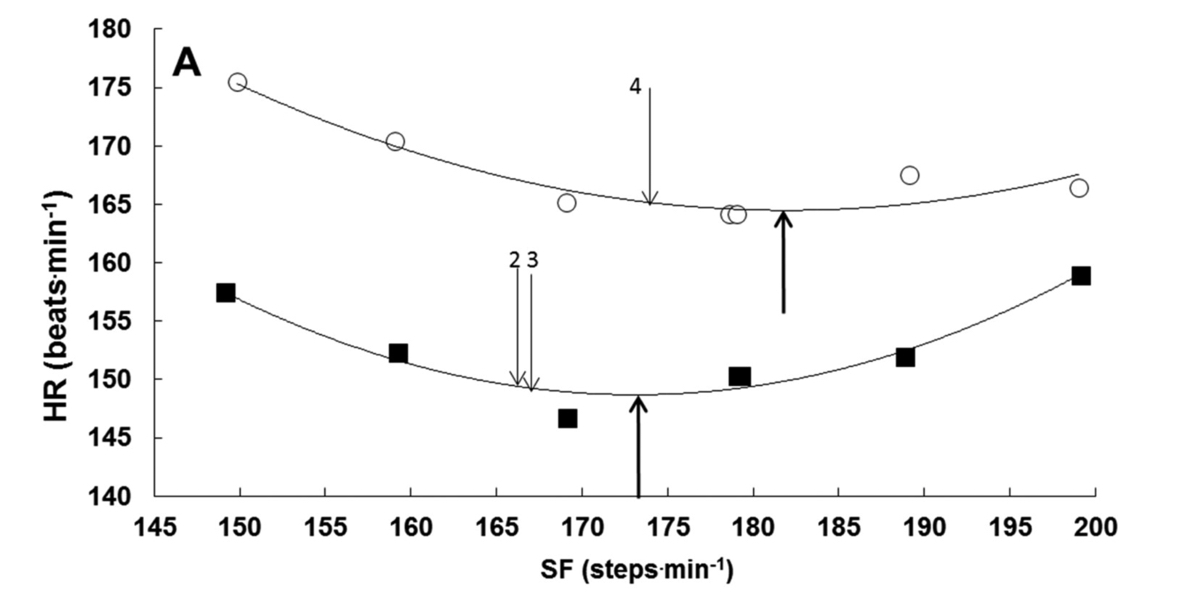

We now additionally know why it is that two humans can run at two very different cadences but perform equally well. Research has shown that we more or less naturally fall into our most efficient cadence, or the cadence that requires the lowest effort, for any given pace. That is, humans self-optimize their cadence!

Humans self-select a running cadence that is near to their optimal cadence. This graph shows the data of one runner where the bottom line and solid squares represent the athlete running at about 13 kilometers/hour and the upper line and open circles represent about 16 kilometers/hour. The runner was instructed to run at various cadences from 150 steps/minute to 200 steps/minute while their heart rate was recorded. The runner was asked what step frequency felt the best (their preferred cadence), and this is signified with the downward arrows. Upward-pointing arrows indicate the cadence deemed most optimal for that speed, or the point of the athlete’s lowest maintained heart rate. Image: Ruiter, C. J. D., Daal, S. V., & Dieën, J. H. V. (2019). Individual optimal step frequency during outdoor running. European Journal of Sport Science, 1–9. doi: 10.1080/17461391.2019.1626911 (8)

What all this means is that the runners with 155 and 203 cadences who finished within minutes of each other at the 2016 IAU 100k World Championships were both likely ‘right,’ or doing what was best for them.

Conclusion

Fiction. Don’t sweat 180 steps per minute. The likelihood is that the cadence you run at any given speed is just about right for you, particularly if you’ve been running for a while and are generally uninjured. How cool is it that we self-optimize our own best stride rates? However, if you keep getting injured, have a physical therapist evaluate your gait to make sure your cadence isn’t contributing to your injuries.

Fact or Fiction? “It’s normal to lose your period; you run a lot.”

I hear it said, sometimes even as a badge of pride, “I lost my period because I run a lot.” It is true that menstrual disturbances occur at much higher rates in active females than our sedentary counterparts. In fact, amenorrhea (the absence of the menstrual cycle for 90 days or more) and oligomenorrhea (cycles greater than 35 days) are reported at rates of up to 60% of women participating in sports (12).

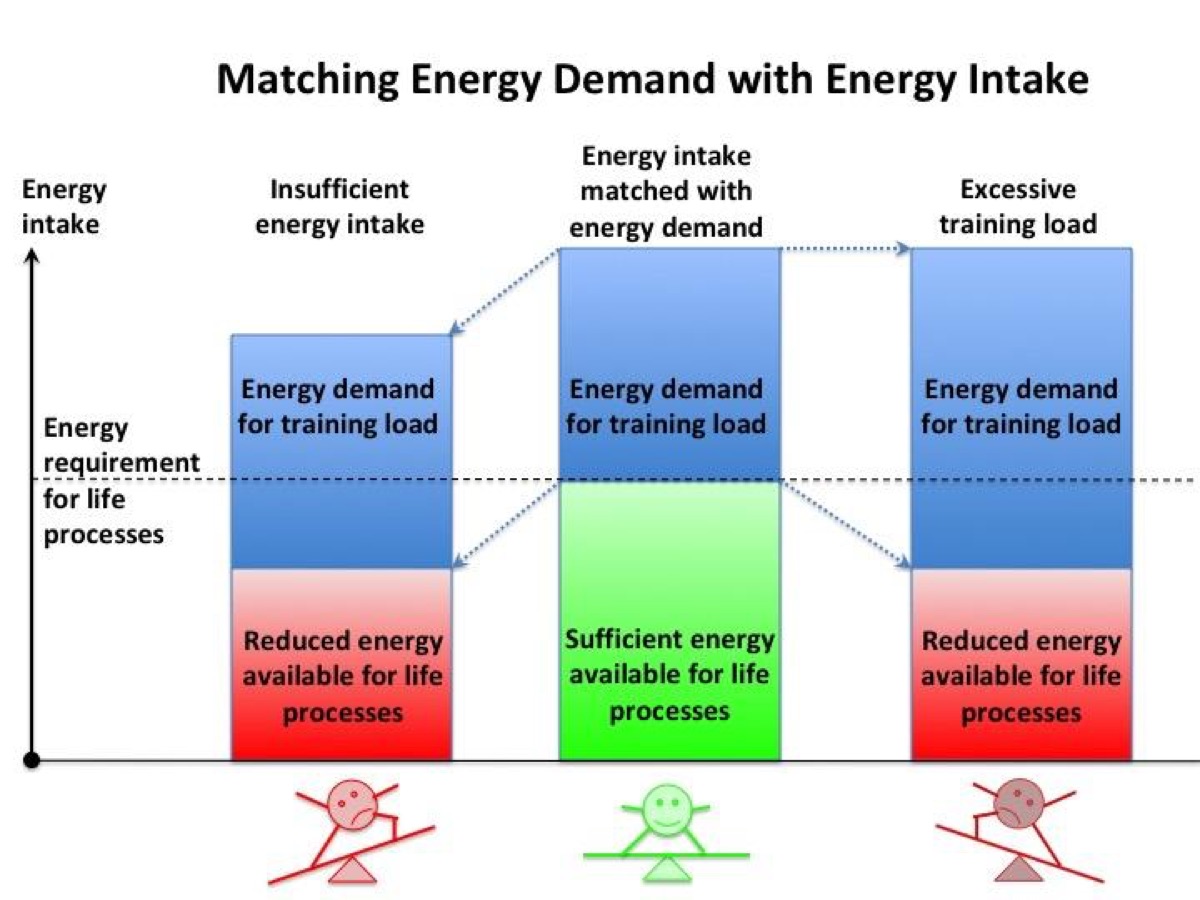

That said, menstrual disturbance is abnormal. Menstrual dysfunction is most commonly seen in female athletes with low energy availability, or where exercise is coupled with inadequate dietary intake. Essentially, the body needs energy to maintain our basic physiologic functions from cellular maintenance, growth, thermoregulation, and reproduction plus the requisites of our training. When your body doesn’t have the energy it needs to do all that, it directs energy away from things like metabolism and reproduction in order to survive. Beyond a decrease in athletic performance over time, if states of low energy availability continue, we see marked changes in bone-mineral density, an increased risk for fractures and musculoskeletal injuries, cardiovascular risk, and neuroendocrine abnormalities such as thyroid dysfunction (9, 10, 11, 12).

Our health and athletic performance are dependent on us matching our energy demand with nutrition. When energy intake is insufficient to meet the demands of normal function plus training load, performance and life processes (metabolism, immune function, and reproductive function) all suffer. Image: Trainingpeaks.com/blog/the-risks-of-relative-energy-deficiency-in-sports/

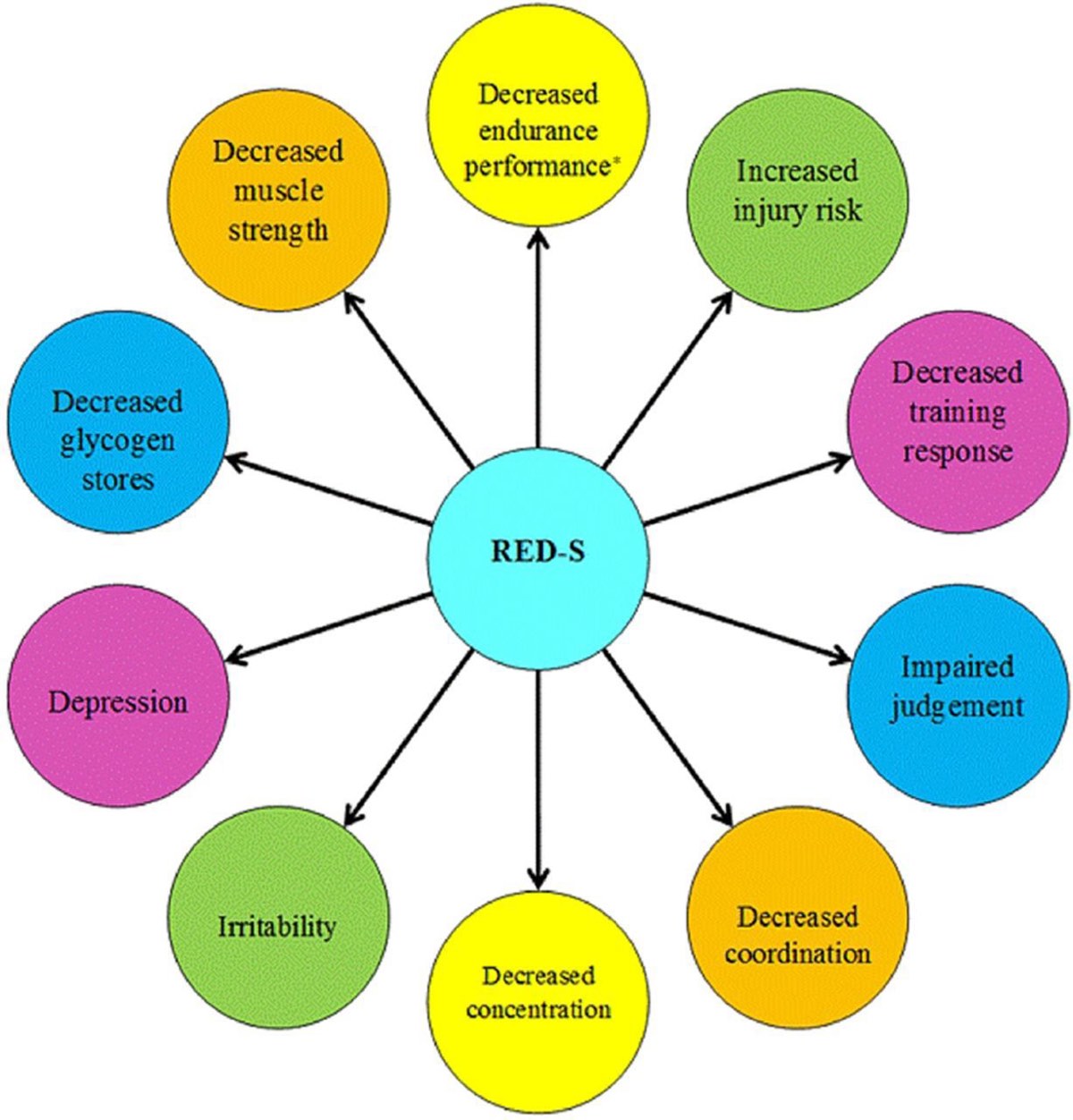

The combination of low energy availability, menstrual dysfunction, and decreased bone density has been referred to as the female athlete triad for a long time. Recently the International Olympic Committee and other research groups have developed a new term called Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S) (9). RED-S still covers the interrelationship between energy availability, reproductive function, and bone health, but it also expands to acknowledge that men also fall prey to low energy availability and its associated symptoms. We have previously written in depth on iRunFar about menstrual dysfunction, low-energy availability, and RED-S.

It should be noted that you can have low energy availability and menstrual dysfunction without struggling with restrictive or disordered eating. As endurance athletes, particularly ultra-endurance athletes, it’s easy to fall behind the demands of a high training load.

Conclusion

Fiction! Training is hard and eating enough for your training might be harder, but that doesn’t make menstrual dysfunction normal. Amenorrhea should not be taken lightly and experiencing amenorrhea for an extended period of time (I swear that is not a menstruation pun) puts you at increased risk for low-bone-density-associated injuries and osteoporosis, fertility problems, and even increase your risk for dementia in the long-term.

The fallout from RED-S affects more than training and race performance and can put you at risk for developing a host of physical and psychological conditions. Image: Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S). (2015). British Journal of Sports Medicine, 49(7), 421–423. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2014-094559 (16)

Call for Comments (from Meghan)

- Which myth have you previously bought into and why? And why is it sometimes easy to believe what we want to believe rather than fact?

- What do you think about this article’s format? What other facts and fictions would you like to learn about? Share some feedback with us for the future!

References

- Coyle, E.F., Martin, W.H., Bloom6eld, S.A., Lowry, O.H. & Holloszy, J.O. (1985). Effects of detraining on responses to submaximal exercise. Journal of Applied Physiology, 59, 853-859.

- HeUerstain H.K., et. al., Principles of Exercise prescription in exercise testing and Exercise Training in Coronary Heart disease, (New York: Academic Press, 1973), P.35.

- Jafer, A. A., Mondal, S., Abdulkedir, M., & Mativananan, D. (2019). Effect of two tapering strategies on endurance-related physiological markers in athletes from selected training centres of Ethiopia. BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine, 5(1). doi: 10.1136/bmjsem-2019-000509

- Grivas, G. V. (2018). The Effects of Tapering on Performance in Elite Endurance Runners: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Sports Science, 8(1), 8–13. doi: 10.5923/j.sports.20180801.02

- Mujika, I., Padilla, S. (2000) “Detraining: Loss of training-‐induced physiological and performance adaptations”.Sports Med.30 (2): 79-‐

- Heiderscheit, B. C., Chumanov, E. S., Michalski, M. P., Wille, C. M., & Ryan, M. B. (2011). Effects of Step Rate Manipulation on Joint Mechanics during Running. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 43(2), 296–302. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e3181ebedf4

- Burns, G. T., Zendler, J. M., & Zernicke, R. F. (2019). Step frequency patterns of elite ultramarathon runners during a 100-km road race. Journal of Applied Physiology, 126(2), 462–468. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00374.2018

- Ruiter, C. J. D., Daal, S. V., & Dieën, J. H. V. (2019). Individual optimal step frequency during outdoor running. European Journal of Sport Science, 1–9. doi: 10.1080/17461391.2019.1626911

- Melin, A., Tornberg, Å. B., Skouby, S., Møller, S. S., Sundgot-Borgen, J., Faber, J., … Sjödin, A. (2014). Energy availability and the female athlete triad in elite endurance athletes.Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 25(5), 610–622. doi: 10.1111/sms.12261

- Hawkey, M., Volberding, J. L., Tapps, T., & Tapps, C. (2017). The Effectiveness of the Female Athlete Triad in Identifying Athletes’ Potential Risk of Long Term Health Consequences.Journal of Sports Science, 5(3). doi: 10.17265/2332-7839/2017.03.001

- Fahrenholtz, I. L., Sjödin, A., Benardot, D., Tornberg, Å. B., Skouby, S., Faber, J., … Melin, A. K. (2018). Within-day energy deficiency and reproductive function in female endurance athletes.Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 28(3), 1139–1146. doi: 10.1111/sms.13030

- Clark, L. R., Dellongono, M. J., Mangano, K. M., & Wilson, T. A. (2018). Clinical Menstrual Dysfunction Is Associated with Low Energy Availability but Not Dyslipidemia in Division I Female Endurance Runners.Journal of Exercise Physiology Online, 21(2), 265–276.

- Prokai, D., & Berga, S. (2016). Neuroprotection via Reduction in Stress: Altered Menstrual Patterns as a Marker for Stress and Implications for Long-Term Neurologic Health in Women.International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 17(12), 2147. doi: 10.3390/ijms17122147

- Kirschen G, Hale L. The Impact of Sleep Duration on Performance Among Competitive Atheltes: A Systematic Literature Review. Clinical Journal of Sports Medicine. 2018. DOI: 10.1097/JSM.0000000000000622

- O’Donnell S, Driller MW, Beaven C. From Pillow to Podium: A review on understanding sleep for elite athletes. Nature and Science of Sleep. 2018: 10: 243-253.

- Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S). (2015).British Journal of Sports Medicine, 49(7), 421–423. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2014-094559

- Nichols, J. F., Robinson, D., Douglass, D., & Anthony, J. (2000). Retraining of a competitive master athlete following traumatic injury: a case study.Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 32(6), 1037–1042. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200006000-00001

- Beil, L. (2018, July 21). The brain may clean out Alzheimer’s plaques during sleep. Science News, 194(2), 22.

- Samuels C. Sleep, Recovery, and Performance: The New Frontier in High-Performance Athletics. Neurol Clin 26 (2008) 169–180