I couldn’t decide. Should I try to cobble together a support team to carry my coat and sandwiches, like proper fell runners (and Kilian Jornet) do, and go all-in on my attempt to set a record on the Paddy Buckley Round? Or should I just go solo, self-supported, hassle- and pressure-free, and have a merry, old bimble and see what came of it–besides squashed sandwiches? In the end, it was a bit of both.

Britain has many fell running challenges, but the three that rule them all are the classic 24-hour ’rounds’ (established circular mountain-running challenges); England’s Bob Graham Round (42 peaks, 27,000 feet of ascent, and approximately 66 miles–the mileage is only a rough guide because as long as you tag the summits, the route between them is up to you), Scotland’s Charlie Ramsay Round (24 peaks, 28,000 feet of ascent, 60 miles) and Wales’s Paddy Buckley Round (47 peaks, 28,000 feet of ascent, 61 miles).

With well over 2,000 completions, including that Catalan chap in 2018, and a wonderful eulogy in the popular book Feet in the Clouds: A Story of Fell Running and Obsession by Richard Askwith, the Bob Graham has all the clamor. The Ramsay meanwhile has the glamour. Only around 140 people have completed it, it’s seen as the most spectacular round and the connoisseur’s choice. The Paddy? Well, people don’t seem quite as excited about the Paddy.

While England’s Lake District is the historic heartland of fell running, races in Wales date to the 1970s. Though if you have sympathy with the idea that for centuries the most convenient method of transport from one place to another in this gloriously lumpy land was to go over a hill, fell, or mountain (which are approximately the same thing) using your own two feet, fell running/walking dates to circa forever. Wales has its own fell-running championships. I was almost born Welsh. But I’ve done just a handful of fell races.

Having gotten intimate (if intimate is the right word for repeatedly getting half your body stuck in a bog) with the Paddy Buckley over the last year, I’d say the round in north Wales’s Snowdonia National Park is the least celebrated of the big three. It’s the trickiest, quirkiest, and most idiosyncratic. Partly because it seemed the least loved, I fell in love with it.

The Paddy is defiantly different. Unlike the other two, there’s no official start point (which adds to the challenge–where should you start from?), technically it doesn’t have a 24-hour deadline (though most try to observe it), there’s no website or club for it, and its namesake has never completed it. It even has two mountains with the same name (so be careful where you arrange to meet people).

I’ve spoken to several 24-hour round record-breakers and opinions are divided as to which of the three is the hardest, but the Ramsay and Paddy are broadly judged to be around an hour slower than the Bob Graham. And the Paddy is probably the one most likely to catch people out.

If you miss the trail (if there even is one), the terrain can be mockingly unfriendly; heather, bracken, scratchy gorse, long wet grass, rock (oh, there’s plenty of shin-whacking rock), and bog (it’s definitely the boggiest). Navigation is tricky in sections and the weather seems more fickle in coastal Wales, having scuppered several record attempts. Misleadingly, a few of the summits are out-and-backs to grassy knolls or insignificant-seeming bumps, rather than clearly defined mountain summits–though it certainly has those too.

The previous Paddy record of 17:42 was set in 2009 by Welsh mountain runner and local Tim Higginbottom. Ostensibly there seems some slack in that time. (Jornet’s Bob Graham record, for example, is 12:52.) But that viewpoint underestimates the Paddy’s idiosyncrasies.

Though I’d completed the three rounds as microadventures with a friend, our times weren’t noteworthy. The Paddy was the only one we failed to complete in under 24 hours. It was unfinished business.

I’ve never considered myself a fell runner. I’m from the Cotswolds, a southern England sheep-farming area of rolling hills (highest point 330 meters/1,080 feet altitude), near south Wales. But I do like lumps and I’ve done UTMB a few times. But that’s on good trails. It’s very different to fell running, which can often feel more like rock hopping, bushwacking, and bog-trotting.

I supported a friend’s Paddy attempt in August of 2018 (supporters are expected to carry kit, food, drink, and help with navigation), my first taste of it. After my own (slow) Paddy in March of 2019, I supported Nicky Spinks on three of the five legs as she completed an unprecedented double Paddy Buckley in May. I also supported my new neighbor, American John Kelly, on three legs as part of his failed ‘grand round’ attempt, where he was trying to complete all of the big three rounds in under 24 hours whilst biking in between them.

Somewhere in amongst all that, it suddenly occurred to me that both my legs and head had accidentally gotten to know the Paddy rather well. I had also run 60 miles three times this year, so my fitness shouldn’t be too far off, either. As a self-employed coach and journalist, I can be a bit flexible with my work hours and could wait for a good weather window. In June, there’s a chance you could get around without a headtorch. My nav is bobbins, so that was key for me.

It seemed unlikely that all these circumstances would fall into place for me again. I had run out of excuses not to have a bash. I stuck a map of the Paddy on the wall by my desk.

I visited Snowdonia one more time and ran a leg and a half at record pace, which felt encouraging. All I needed was good weather. It rained. And rained some more. It may sound a bit, er, wet, but a fast Paddy needs a spell of fair weather. There’s a lot of rock, which needs to be dry. And the bogs on the longest leg, from Capel Curig to Aberglaslyn, can be waist deep. Finally the forecast turned.

As I drove up through Wales, it rained the whole way. Thankfully, unusually, Snowdonia seemed the only dry place in the country. I deposited three food and drink drops and tried to get some sleep.

Other than my wife, I had told two people. One was able to help–probably, he said. The other not. It felt like an exciting secret.

After a banana and a stale pan au raison, I set off from Llanberis at 4 a.m., Wednesday the 19th of June, solo, under a big moon, on a 17:40 schedule. The weather was perfect. Clear skies and t-shirt temperatures.

I didn’t want to overcook that first long climb, but it also occurred to me that the time I reached summit number one could set the tone for the entire day. Would I be chasing the 17:40 schedule, already? Or ahead, feeling happy and relaxed? I missed the optimal line, but hit the summit cairn two minutes up. Smiles. Just 46 more to tag now.

That first leg was glorious. The sky was clear. Brilliant light. I felt lucky and happy. This was just a cracking day out in the hills. Whatever will be will be.

I was alarmed to be 20 minutes ahead of record pace at the summit of treacherous Tryfan, one of the greatest but also most daunting mountain views in Britain, 18 miles and nearly five hours in. It was all going too well. I really wasn’t pushing hard.

I got caught up in daydreams and missed the best line of descent off the bouldery summit. And the second-best line too. Getting caught in a no man’s land in between–huge boulders, heather, and hidden potholes. I wasted some time, but I did’t get grumpy. It was a beautiful morning and I was doing what I love.

It was a long slog up Pen Y Ole Wen (pen is Welsh for head/top), but then there was glorious plateau and ridgeline running, rocky in places. I tried not to look at my schedule. I knew I’d do better if I was just enjoying it. But after dodging the optimal line again descending Pen Llithrig y Wrach, I was around 15 minutes ahead still at Capel Curig, where I eagerly grabbed my stash of supplies, including brioche rolls crammed with nutter butter, banana, and chocolate spread.

This leg is the longest, the boggiest, often the one that sinks runners’ spirits. The day was warming up. I felt I was moving well enough, so I was a little miffed to be only 10 minutes up overall at the rocky summit of Carnedd Moel Siabod. I ran the descent quite hard, but gained back no time by the next peak. Nor the next. In fact, minutes were slowly seeping away.

Then it got boggy. Not waist deep, but not far off, which slowed me more. As did identifying the exact summits of the byzantine string of bumps over the next couple of hours. The schedule seemed much tighter for this leg. Somehow I was now behind it. I was about halfway around the round and I was mysteriously hemorrhaging time against a tight schedule. I went into preservation mode. It was important to stop the leak, stay focused, and be efficient.

I heard a cuckoo, as I had done when here with Nicky, a rare sound in Britain now, as I climbed the leg’s last peak, the brutish Cnicht–hands strangling grass it’s so steep. I ran hard off it hard and on the stony trails and road section that followed, not thinking of gaining back time, just trying not to lose more.

Scooping up another drop bag, I left Nantmor 12 minutes behind record pace. I tried not to let myself feel frustrated. This was all just an experiment really. It’s just a fun day out, right?

I’ve never found a good line up through the boggy bracken to Bryn Banog. Gnah! It was warm. I got dehydrated. Snails started overtaking me. The higher Moel Hebog, too, seemed monstrous. I was losing more precious time. My motivation dimmed. Sub-17:42 no longer felt possible, but the second-best time was 18:10. I could maybe still beat that, which would be pretty cool. And I was having a cracking day out anyway. I sent a silly-face selfie to my wife and kids.

By the end of leg 4 (Pont Cae’r Gors), I was about 25 minutes behind the record. But I had a secret weapon: local speedster Michael Corrales (Dark Peak) and his dog Dusty. I had only met Michael once before, on John Kelly’s grand round attempt. We’d got on great and he knew parts of the Paddy really well. He nearly hadn’t turned up. His car window was broken, replaced by a sellotaped plastic bag for now. “I really, truly think we can still break the record,” he said.

I didn’t believe him. And I didn’t really feel like pushing any more. But I felt so grateful he’d made the effort to join me (I didn’t know about his car yet) that I felt I owed him at least some puffing and panting. He’d gradually see I wasn’t really up to it, I figured, and we could just relax and enjoy it.

But Michael had different ideas. He encouraged, cajoled, and politely bullied me on the long slog up Snowdon (1,085 meters/3,560 feet), the highest point in Wales, in the gloaming. For the first time ever, I could see all of Snowdonia, bathed in golden light. We made up a few minutes at the first peak. A few more at the second. “We really can do this,” he insisted. I just grunted. My climbing was pitiful despite the jelly babies I was eating.

“If we could get to the top of Snowdon for 20:01, it would make me very happy,” he said. I did that at least. Known as the busiest mountain in Britain, there was no one else on the summit but one a solitary fell runner, wearing inov-8 Mudclaws like me. He wished us luck and really seemed to mean it.

After Garnedd Ugain we flew. We hammered the descent like it was a one-summit fell race (which is what Michael specializes in). My legs protested loudly. I ignored them. I hoped Michael would stop pestering me, but we kept on making up time.

We had an hour left. “Just four summits to go,” said Michael, who had given me all his water though was clearly thirsty himself. They were grassy summits, with good running. But they looked like tidal waves to me. I kept working, only to shut him up. The arms of my top were caked in sweat.

“If you have anything left at all, now is the moment to use it,” said Michael on the penultimate climb, auditioning excellently for the role of super-coach in the next “Rocky” film. I did what I could.

“From the final summit, the schedule has 30 minutes to get to Llanberis!” said Michael, excitedly. We agreed that seemed generous. We had a chance. Oh pants, I had to keep running hard.

The final descent was the perfect gradient. Firm grass, runnable, the promised land below in the fading light. We hit tarmac. Thankfully the main road was quiet, as I had no plans to stop for traffic. My Suunto says the last mile was 6:23 pace.

I grabbed the post of Llanberis Lake Railway where I had started, breathless, at 21:31. My total time was 17:31:39, 11 minutes under the previous record.

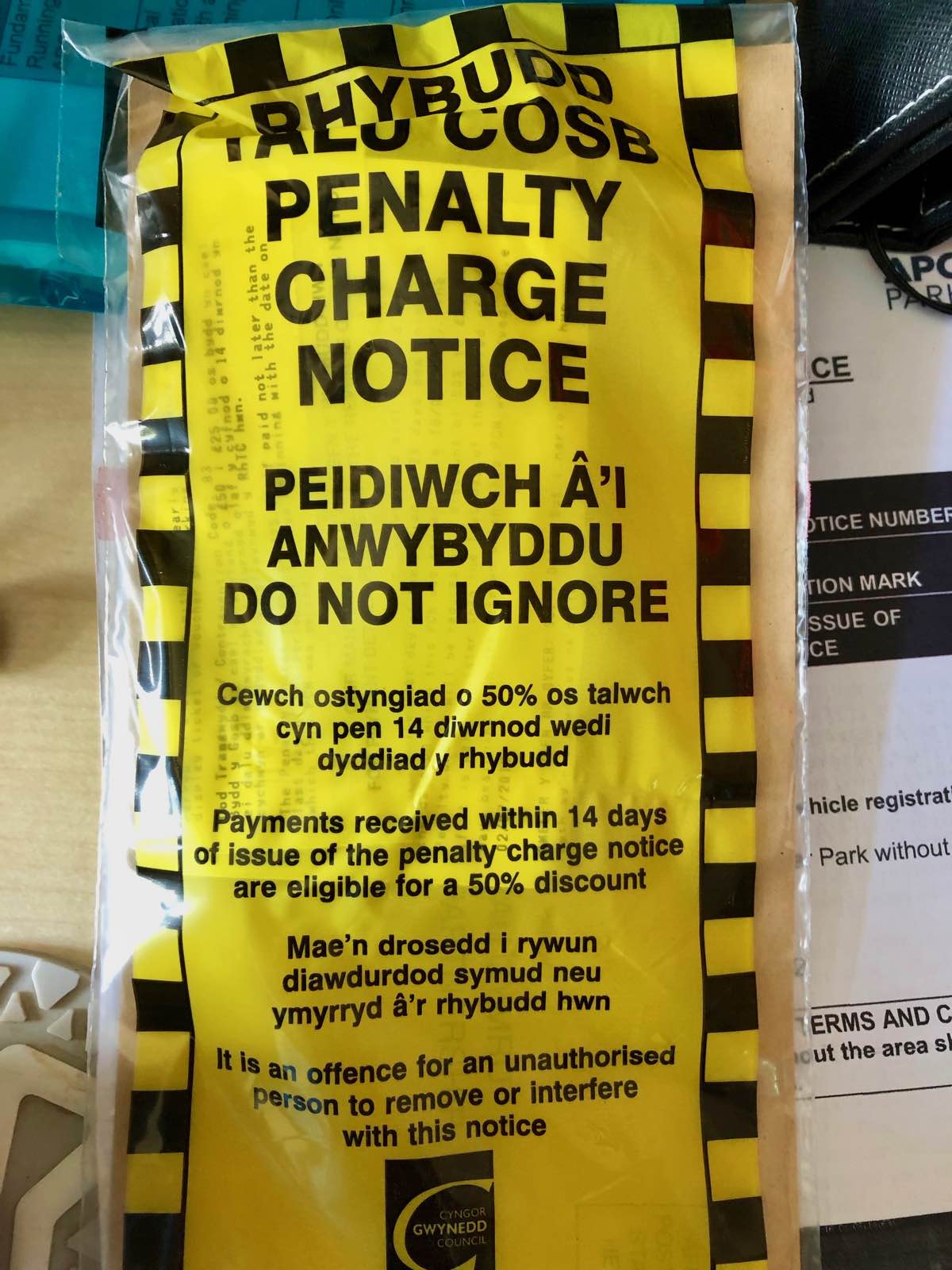

It’s not a record I expect to have for long. It was just an experiment that went right. And I still wouldn’t call myself a fell runner. But it sure took the edge off the parking ticket I found afterward on my car windscreen.

Damian Hall’s Paddy Buckley Round Kit

- inov-8 MUDCLAW G 260 – Lake District-based inov-8 specializes in grip and adding revolutionary graphene to their outsoles makes their sticky rubber really last. These shoes are phenomenal for British fells; they grip on almost everything and gave me no foot issues.

- inov-8 Race Ultra Pro 5 Vest – Reams of pocket choices, adjustability for great comfort, versatile options for softflasks (and poles). You don’t notice a great pack or race vest and I forgot I was wearing this.

- Suunto 9 Baro – As I had no one to verify that I reached most of the key summits, a GPS running watch trace of my run was critical for record verification, so I was grateful for a reliable watch that could potentially be a great help with nav, too.

- Mountain Fuel Feel Good Bars and Sports Jellies – I’m not a huge gel fan, but these jellies go down really well. They’re fast-acting and pleasant flavors I actually want. The flapjacks magically stay moist and are, again, great flavors I actually want to eat, especially Ginger.

- Harvey Maps – Harvey Maps make excellent maps for all three of the main 24-hour rounds.