The majority of us have probably said, “I want to feel better/faster/stronger when I run.” Often when people start running, an emphasis is put on running fast. I’d argue that in trail running, ‘fast’ takes all the credit while ‘efficiency’ quietly and humbly does most of the work.

I think of efficiency in running as moving smoothly and quickly with little to no wasted energy. Often, efficiency translates to fast over the course of an entire run, but not the fastest you can run at every moment of that run. Efficient movement will almost always take you farther while feeling better than speed alone. Let’s discuss efficiency and powerhiking.

Efficiency in Trail Running

When we trail run, whether it’s a regular run or a race, our basic goal is to get from point A to point Z–from the beginning to the end of the run. Some runners additionally seek solitude, others prioritize taking photos or enjoying the beauty along the way, and some look forward to the aid-station buffets. But usually, regardless of your level or competitive nature, getting to the finish sooner rather than later and feeling as good as possible are also pretty high on the priority list.

In a race scenario, let’s frame in our minds the idea that getting from the start line (point A) to the first aid station (point B) as efficiently as possible will usually get us from the start line (point A) to the finish line (point Z) faster than we could have imagined. What does the travel between points A and B look like in this scenario? It is not necessarily the fastest you can run, but it’s the fastest you can move while still exerting an effort you can sustain through the end of the run. On a steep uphill or a flat section filled with slippery rocks, that might mean powerhiking and not running. Why? Because running in that moment might require more energy than is sustainable for you and that run.

Are you wondering what powerhiking is? Powerhiking is moving quickly, strongly, and smoothly while not actually running. But powerhiking isn’t taking a walking break! It’s hiking with intent and purpose. Some people who have practiced a lot can powerhike at what others would call a running pace.

Instead, consider powerhiking is a tool to pace yourself, conserve energy, and move effectively in hilly terrain. If you simply run as much as you can, you may use up all of your energy before your run is done, which might rob you of minutes or hours at the end when you become tired, the fun and feel-good factors, and perhaps even a finish of a race. Our goal is to maintain a consistent effort during the course of our trail run, rather than a consistent pace. This means that, when the terrain gets steep, you’ll want to powerhike rather than run so that you don’t tire yourself out early.

In powerhiking, it’s crucial to know when to powerhike and how to do it well. In the rest of this article, we’ll explore these concepts.

When Should I Powerhike?

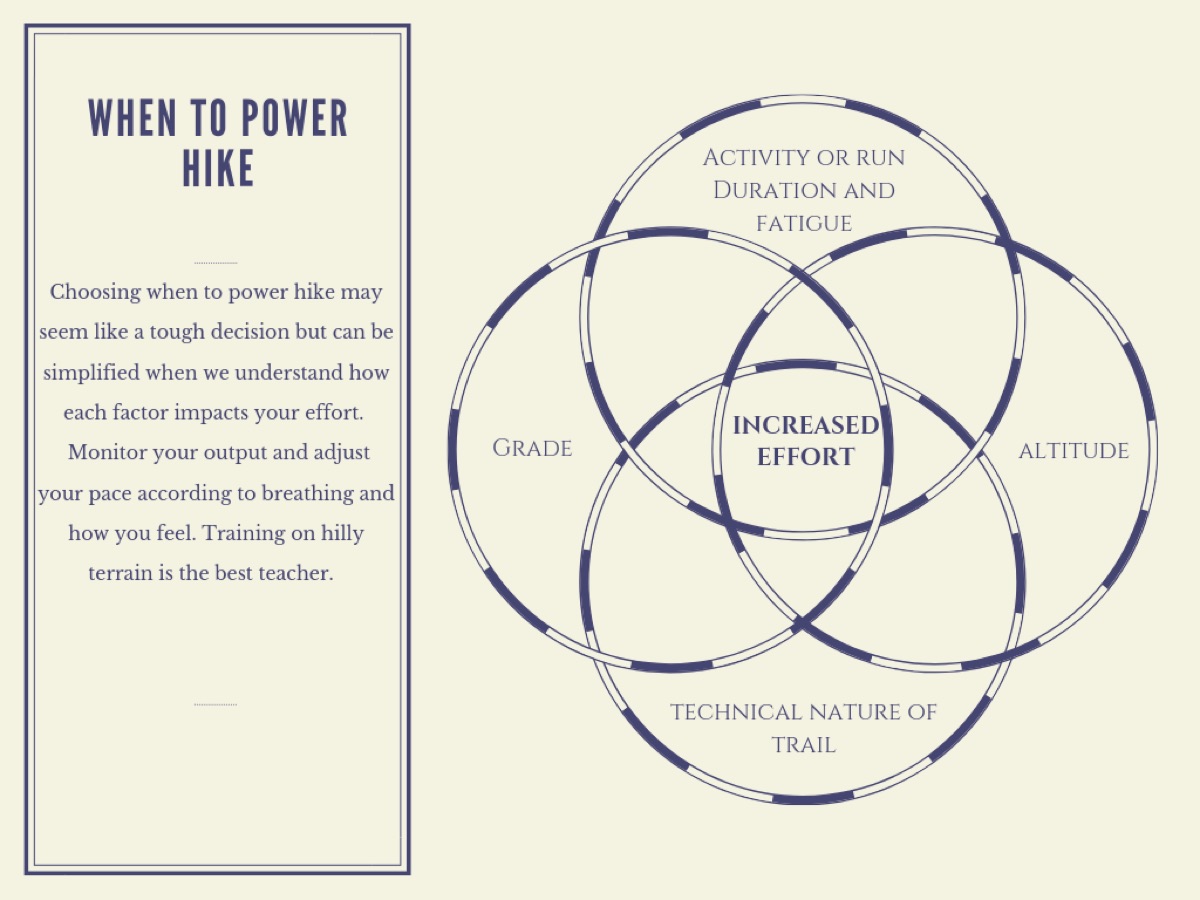

Deciding when to powerhike depends on a variety of factors including a trail’s steepness, technicality, and altitude; your run’s distance and amount of climbing; as well as your experience on hilly terrain, fitness, and fatigue. In reality, these factors are interdependent, which at the outset might make you think that the decision of when to powerhike is complex. In actuality, it’s fairly simple and we’ll get there shortly. First, let’s better understand how these factors influence our decision to powerhike.

Trail Steepness

There is no magical grade, or steepness, on which you should always powerhike rather than run. This depends on a number of things, especially the run’s distance and your fitness. For example, if you’re on a short run, you might only need to powerhike one climb, but on a run that lasts several hours you might be better off powerhiking them all. And, after a summer of training on steep terrain, you might find you can run a lot more of the climbs than you did in the spring while still feeling like doing so is easy.

A study by American trail runner Keely Henninger and others states, “We found that there is a range of angles for which energy expenditure is minimized. At the vertical velocity tested, on inclines steeper than 15.8 degrees, athletes can reduce their energy expenditure by walking rather than running” (1). So, their research essentially showed that, when you’re on a treadmill and traveling at the speed they tested, you will use less energy to walk rather than run when the terrain is steeper than 15.8 degrees. Like we said before, there are many other factors that might influence the inflection point between you running and powerhiking, but consider this a good starting point.

Activity Duration

Is your event short enough where a high output of energy can be sustained for its duration? Or is the event longer? Just because you are fit enough to run an entire climb doesn’t mean you should. Always think about the climb that’s in front of you in the context of your whole run and ask yourself, “Will running this climb positively or negatively impact the rest of my run?” With this longer-term thinking, we see that a decision to powerhike also depends on the length of your run.

Trail Technicality

Sometimes a trail is simply so rocky or rooty that powerhiking allows for better foot placement and therefore more efficient movement even if it’s not particularly steep.

Fatigue

At some point during a run or race, you may simply become too tired to run a hill. Multiple research studies have shown that at a speed of around three to four miles per hour on flat ground for most people, it’s simply more efficient to walk (2, 3). Of course, this run-powerhike transition varies based upon multiple factors, but here’s another data point to consider.

And while we’re here, what if you’ve burned too much energy too early in your run and you can’t run anymore? Don’t give up! Powerhike with determination, and you might find you still get to the finish faster than people running around you.

Altitude

If you’re at over 5,000 feet altitude and not living there and used to it, it will impact your overall effort. It may be better to powerhike a hill at altitude that you could normally run at sea level.

Overall Thoughts on When to Powerhike

Alex Nichols, who has been a winner of the Mont-Blanc Marathon, second at the Western States 100, and has the Nolan’s 14 FKT, says, “Pay attention to your effort. I don’t make a predetermined plan of when I will hike and when I will run, it is more based on my breathing and effort. I also try to remind myself how much longer I have to go. So when I get to a big climb early on in a long run or race, I tell myself that I still have significant running ahead. That helps me realize that I probably shouldn’t be breathing like it is the last 400 meters of a 5k. When I decide to walk, I focus on my cadence and efficiency. I see a lot of people who stop running and start strolling. I think it is really important to stay quick with my feet and make sure I don’t slip on any of the steps. I like to think of it as walking with purpose.”

What Alex is getting at is the beautiful simplicity of knowing when to powerhike: it’s about feel. It’s about knowing what effort is sustainable and what isn’t. And, ultimately, training and racing experience is the best way to find your threshold of when and where you should switch from running to powerhiking. You know you. Listen to your body and be honest with yourself.

This Venn diagram can help visualize how each of these components (among many others) must be considered in combination with each other:

How to Powerhike Well

We all know that there’s walking, and then there’s walking. There’s the meander down the street after dinner and there’s the hustle through the grocery store that’s closing in two minutes. In the second part of this article, we’ll talk about how to powerhike well.

Powerhiking Form

- Focus on pushing off the ground with stability and power.

- Lean into the hill at the waist, but don’t hunch over at the shoulders. You want your center of gravity forward and working for you as you climb, and you want the lungs to be able to expand fully while hiking. Using poles, which we discuss below, can aid in keeping good powerhiking form.

- Be fluid with your motions. If the climb is on road, shuffle your feet to conserve energy. If it’s technical, pay attention to foot placement.

- Let your arms do some work. You might find that swinging your arms strongly helps maintain forward momentum. Or you might find that pressing down on your knees with your arms helps you get uphill. We’ll talk about this latter concept shortly.

Practice

Simply said, the best training for powerhiking is… powerhiking. Get out on steeper terrain and get familiar with how climbing on it feels. Seek out terrain–trails are best but even a steep road or a stairwell in an office building will do–that exceeds a 15 to 20% grade and incorporate it into your training. Finding trails that climb 800 feet per mile (or 150 meters per kilometer) can be tough in some areas of the world, but finding short sections of trail, roads, or stairs that climb at this grade might be possible. If you don’t know of any steep terrain near you, try using the Strava Segment Explore feature and click ‘Steep’ to find stout climbs.

While out there, notice the difference between running and powerhiking the same hill. Do your legs burn when you run but don’t when you powerhike? Do you struggle to talk while running but have no problem when powerhiking? Monitor changes in your breathing, heart rate, and how your legs feel.

What if you don’t live near a hill and you have a mountain 50k coming? You can still practice powerhiking on a treadmill! Additionally, there are other things you can do to shore up your strength if you can’t train on steep terrain. This article offers a full-spectrum approach on how to train for mountainous trail running when you don’t have access to steep terrain.

Should I Use Poles or Push on My Knees with My Hands?

The answer to this powerhiking question, aside from being completely ridiculous sounding if asked in the company of anyone but trail runners, depends on the terrain, regulations at the race you’re training for, as well as your personal experience and preference.

Hiking poles are popular because they help maintain an upright form and transfer some of the work from the legs to the arms while powerhiking. Using your hands to push your knees down on each step has a similar effect, but runners must remember if powerhiking with hands on knees not to collapse the torso.

Runners with a skiing background often feel more comfortable using poles to add climbing power and even to disperse impact and maintain balance on downhills. Many runners only use poles on long uphills before stowing them in a pack for the descents. On courses that constantly roll and would require putting poles away and taking them back out over and over, many skip the poles and opt for hands on knees when needed. On courses that have significant sustained climbs and fewer transitions, poles are most popular. Spending a few runs testing each method on varying hilly terrain will give you an idea of what works best for you.

Maintain Your Momentum

Getting lulled into a stroll or distracted by scenery or your trail snack can cause you to forget to start running again when the trail levels out. Keep alert!

When you switch from running to powerhiking and back again, maintain your forward momentum. When you want to switch back to running after powerhiking, take a few quick and short hiking steps just as the terrain flattens, swing your arms hard, and transition to a run. And when it’s time to convert from running to powerhiking, make sure you’re still moving with strength and purpose. Remember, it’s not a walk break, it’s powerhiking!

The sign of a great powerhiker is fluidity between powerhiking and running. In this video, watch professional mountain runners Ricky Gates, Jim Shine, and Kilian Jornet as they climb during the steep, rugged but only-5k-long Mount Marathon Race in Alaska. Take note of how they beautifully flow back and forth between running and powerhiking. And while you’re watching, watch how they press on their knees with their hands while powerhiking, too. While you might never want or need to climb something this steep or fast, these runners provide a great example of efficiency.

Conclusion

I ran the 2016 UTMB, a 105-mile (170k) race in the European Alps that circles Mont Blanc on steep mountain trails, climbing about 33,000 feet (10,000 meters) along the way. By analyzing cadence data taken by my GPS running watch during the race, I calculated that I powerhiked 46% of that race, if you measure by time. That is, of the 22 hours and 41 minutes on the course, I spent 10 hours and 25 minutes powerhiking. Maybe you’re thinking, “If you had run more, you could have finished faster!” I’d instead argue that I performed at a level I was happy with because I hiked early and effectively. [Editor’s Note: He took fourth place at the competitive event.]

Now get out there and practice powerhiking in your training! Powerhiking is a part of trail running. Embrace it as a tool of efficiency and develop it. Become one of those powerhikers who can hike faster than some people run. Remember that prioritizing speed never prioritizes efficiency, but prioritizing efficiency can prioritize a faster finish time–which is, indeed, speed.

Call for Comments (from Meghan)

- When and how do you decide to powerhike instead of running? What physical sensations and elements of the run go into your decision-making process?

- Can you share any tips you have on how to powerhike well?