To spend time with Eric Senseman is to feel truly and finally understood. He looks at you with concern and interest, clearly indicating that what you’re saying is revelatory and wise. He seems surprised, too, but surprised at himself, as if he’s inwardly wondering how he could have ever lived his life without you. He flips his wave of thick brown hair back and forth without ever breaking eye contact, and his mustache quivers with anticipation for what visionary insight you might reveal next. Eric Senseman validates you, completes you. He is what all friends aspire to.

But, like a cool town or the latest indie music, everyone knows it. And once you go out in public with Eric, and you see his other friends and how he also endows them self-actualizing concern, your heart starts to break, realizing you could never be his only friend, that his care must by nature be spread as widely as possible. Eric Senseman embodies the paradox of the caregiver: his concern connects you by its power and yet divides you by its breadth. To know Eric Senseman is to be truly and finally heartbroken.

I have experienced all this myself. Yet such is my commitment to our connection that I have no choice but to do my duty to his story. Like Victor Frankenstein bitterly assembling his second monster in a storm-ravaged cabin in the Scottish isles, I must grimly commit to the page Eric’s profile despite the tremendous misgivings brewing in my tormented soul. I take no pleasure in this, but the choice is not mine to make.

The Start

Eric Senseman is a critical thinker, just let him tell you: “I graduated from Texas Christian University with a degree in philosophy.” What that means in real-life terms, besides the fact that he’s obviously never going to get a job, is that he likes to think about stuff. But apparently not too much. “I [went to graduate school] to get a Ph.D.,” he told me in a recent interview, “but after a while I realized that it just didn’t have enough relation to people’s lives.” In other words, he wants to work just hard enough to be able to cite more references than you, but not hard enough to finish what he started. Turns out, this is a metaphor for his whole life.

He was born in St. Louis, Missouri the middle child of three. He played sports as a kid. He went to school. He had a childhood. “Did anything happen to you between the ages of five and 18 that I need to know about?” I asked him.

He shook his head derisively. “Of course not. Five to 18? Nothing happens in anyone’s life.”

But that’s not entirely true. He went to a private, all-male high school in St. Louis and calls it an incredible experience. Whereas to me that sounds a bit too much like the movie Dead Poets Society, Eric says he felt much freer than most high-school kids. “There was just less to worry about in school, and all of my friends did everything together. I loved it.” He’s 29 now, and I asked if he went to his high-school reunion.

“No.”

“Really?” I asked, bewildered. “I would have thought for sure that you would have, you’re, like, best friends with everyone.”

“Yeah, well,” he said, “I’m already in regular contact with all the people from high school who matter to me. I mean, just last week I spoke on the phone with four different high-school friends.”

How many high-school friends did you talk to last week? Yeah, me neither. But there was one major deficiency of his childhood that will unfortunately never be corrected:

“Have you ever read Harry Potter?”

“No. Well… maybe the first book.”

And that was the first time Eric Senseman broke my heart.

Books and Business

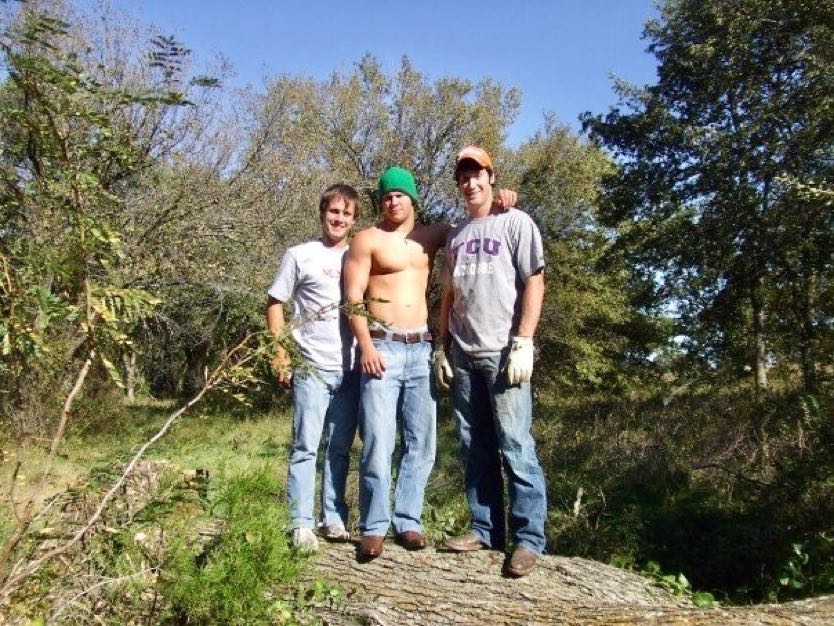

Eric’s sister when to TCU, so he went too. Once there, he joined a fraternity and continued a process begun in high-school football and wrestling: “I got huge, dude.” Huge like buff. Look at this meathead:

Eric Senseman (middle) with friends in his meathead college days. All photos courtesy of Eric Senseman unless otherwise noted.

One of his classes was logic, or “the study of principles and criteria of valid inference and demonstration.” It’s basically a way of building arguments like math problems: if A is true, and B is true, and if A + B = C, then C must be true as well. It gets super complicated after that, but nerds like Eric Senseman really get off on it. Enough so, in fact, that he decided to major in philosophy. He graduated in 2011 with a Bachelor of Arts degree in philosophy and then went on to get his master’s in the subject from the University of Wisconsin-Madison two years later.

College is extremely social, and during his sophomore year of undergrad, Eric found himself spending time with members of the cross-country team. He liked them enough to try out for the team, and then spent the next three years running track and cross country. They would run hard and party hard. The friendships he made there are still some of his closest, right up there with all of his high-school friends, his friends from the non-running parts of college, and most of the people he has met since graduating seven years ago. His phone’s contact list must be out of control.

It didn’t take long for him to transition to the trails after undergrad. His UltraSignup results page records a handful of U.S. Midwest ultramarathons that he managed to squeeze in between doing things like writing 50-page philosophy papers, reading Arthur Schopenhauer, and–literally–consuming everything Ernest Hemingway ever wrote. After two years, however, he decided to forsake his Ph.D. program. “The higher you get in a doctoral program, the more you’re required to concentrate your studies,” he says. “After a while, I felt like there just wasn’t enough connection to real life anymore. So I finished up my master’s and graduated.”

“Was that a hard decision?”

“No,” he said. “Once I realized that I was unhappy, it made perfect sense.”

Following grad school, he and a friend founded a solar-power company and spent a year traveling extensively trying to get it off the ground. In the end, the banks providing the capital refused to allow them to operate in the manner they believed best, and he left the company. It was an extremely complicated and exhausting experience that deserves much more explanation than this paragraph. But Eric only speaks of it positively. “I learned so much about business and money and the real world through that experience. I use that knowledge every day now.”

Today he’s one of two employees at Squirrel’s Nut Butter in Flagstaff, Arizona. He lives with his girlfriend Jacky in a home frequently populated by friends either stopping by or staying in the spare bedroom for weeks at a time. He runs a lot. He drinks beer on the porch, and goes to trivia night at the sports bar, and curates his mustache for hours every day.

Running Fast

The Coconino Cowboys are “a bunch of reckless runners and best friends from Coconino County (Flagstaff) Arizona. [They] are united by the desire to push each other in training and learn to embrace the suffering.” That’s according to their website, which also includes such pithy slogans as: “A pact was made;” “Cowboys VS Everybody;” “Work hard, win easy;” and, most succinct of all, “Bang bang.” Their official slogan is “The Canyon Makes Cowboys,” which is a reference to the Grand Canyon, in which the group apparently trains together on a regular basis. In a sport dominated by the aesthetic of bearded, nomadic hippies dedicating their lives to simplicity and long runs in wild places, the Cowboys’s hyper-competitive rhetoric can incite sneering contempt. Specifically, it can incite the kind of sneering contempt that people have when they’re pissed they didn’t think of a good idea first.

Nevertheless, the words the Cowboys use sometimes feel a bit too aggressive for our polite society. It also seems to run counter to several of the members’ personalities. Like Eric Senseman, for example. He’s a nice guy, not aggressive, better looking than you but you forgive him for it because he makes you feel interesting. How can this guy, who’s so well-versed in concepts of image and self-intention that he can literally cite people like Schopenhauer and Immanuel Kant on the subjects, be on a poster all over Olympic Valley, California before the Western States 100 that says, “Cowboys vs Everybody?”

I don’t know. But I do know that Eric Senseman is competitive. When I asked what some of his goals were for the next few years, he said, “I want to run really fast in races.” That’s a good way of phrasing something that might be taken as conceited if put any other way. He wants to compete, and he wants to win. There’s no need to apologize for wanting to be your best, and running is a great sport in which to try to be your best because the results are so exact. You got first place, or third place, or maybe 78th, but regardless, you always know your position. There’s no ambiguity, which must be a welcome reprieve for a philosopher.

Eric looking a little… worked after finishing his first 50 miler at the 2011 Minnesota Voyageur 50 Mile.

And then, who doesn’t want to run with friends sometimes? You go for a run, you talk and laugh, then you go eat some pizza, maybe drink a beer. Being social is being happy, not all the time of course, but if you don’t actively organize your social time as an adult then it slips away real quick. And then, if you’re already running with the same group of people all the time, why not form a group, get a name, make some T-shirts? It’s fun! Especially if you are all good enough to win races, then maybe other people might buy those T-shirts too, giving you a little cash to take more advantage of your desire to run fast. You’re also spreading the love, building some hype, putting a little honest pressure on yourself to do well. And if you need to be a little dramatic in your slogans to get that attention, who’s it hurting? The photo behind the slogan is clearly of a group of friends having a good time. There are no middle fingers out, no frowns, nobody’s too cool for you. It’s all. Just. A game.

Relax.

In 2013, while in grad school in Wisconsin, Eric ran the American River 50 Mile, two different The North Face Endurance Challenge Series races, and something called Surf the Murph 50k in Minnesota. His worst finish was fourth place. The next year he ran even more competitive races like the Leona Divide 50 Mile and the JFK 50 Mile, again never finishing lower than fourth. In 2015 he blew up hilariously at both the Speedgoat 50k and JFK. Since then, he has pushed into the most competitive races in the country and even raced in Europe. His best results are a fourth place at the Lake Sonoma 50 Mile this year and a big ol’ W at JFK last year, among numerous other top 10s. Racing is hard and he’s pushing himself into new territory. Few runners have immediate success in ultrarunning, and Eric’s trajectory at this point seems on track for him to learn from his failures–like his race at this year’s Western States, his first-ever 100 miler–and improve on them significantly. Watch out for him.

The End

“If you don’t want a man unhappy politically… don’t give [him] any slippery stuff like philosophy or sociology to tie things up with. That way lies melancholy. Any man who can take a TV wall apart and put it back together… is happier than any man who tries to slide-rule, measure, and equate the universe, which just won’t be measured or equated without making man feel bestial and lonely.” -Ray Bradbury, Fahrenheit 451

Intelligence is not a measure of the things you know. Facts are only one part of intelligence. Really intelligent people are such because they can use information differently from the rest of us. Their gift is their ability to connect information in novel and creative ways. Obviously, knowing a lot of things is a crucial part of intelligence, but it’s not enough. Simply knowing trivia without being able to apply it is like having a full tank of gas but no accelerator pedal in your car. A philosophy major might not get you a high-paying job right out of college like a science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) degree might, but it’ll undoubtedly give you the tools to live your life more honestly, more humanely, and much more intelligently than if you focus on numbers alone. This is not to say that numbers-based careers are unimportant, but it is to say that our culture’s focus on numbers is disproportionate and in this way potentially damaging. A society that puts all its emphasis on numbers without asking what they mean does itself a great disservice by eliminating critical thought from discussions of value.

Trail running is fairly intellectual, as far as sports go. How people do things is often as important as what they do. Criticism of the Coconino Cowboys can almost always be boiled down to people perceiving that they aren’t approaching the sport or the trails in the right way. Surveys of the sport indicate that a large number of trail runners have attended at least some post-secondary education, and are wealthy. The last point is often connected with an emphasis on values. People who don’t have to worry about where their next meal is coming from are freer to think about what that meal may be. Thus, trail runners have the opportunity to care about how we participate in our sport, and since our sport is centered in a larger outdoor culture we adhere to certain cultural imperatives. Outdoor recreation has always been heavily reliant on intangible aesthetic values, from the 1700s to today, with adventurers constantly developing these values as they’ve expanded into ever broader landscapes and ever wilder pursuits. In this context, Eric Senseman is an ideal representative of what our sport is now and can be yet.

In Eric’s own words, “It’s really very easy to go through life without serious reflection. It’s easy to acquire convictions hastily and to believe that one’s life is of the utmost importance. It’s much more difficult to think critically, to acquire beliefs meticulously, and to understand that we as individuals aren’t special or especially important.”

I don’t think Eric would dismiss anyone for doing the opposite of that, for taking an easier road and holding beliefs without considering them too closely. But there’s a particularly fulfilling quality of life that accompanies the struggle to understand the world and your place in it. That struggle can be painful and it is never won, and there’s honestly not even a way to define the terms so that you might compare yourself to someone else. You can argue about the ambiguities of what living a considered life even means, which to many people means the whole conversation is a waste of time. But it’s not. Philosophy aims to rationalize these ambiguities as far as possible, but the cutting edge will always be blurry. That doesn’t mean it’s pointless. So take your own path and think your own thoughts, but if you ever get to meet Eric and talk with him, you might get a sense of what I mean when I say that knowing Eric is knowing what it’s like to be interesting, to have someone actually listen to what you say and consider it. And I hope you’ll then ask why he makes you feel that way, and why it doesn’t happen with everyone you talk to.

This article has taken me months to write because when I conceived the idea I immediately suckered Eric into a 1.5-hour interview about his whole life and then spent two months wondering why that felt so pointless. Now I know it’s because the big movements in Eric’s life have nothing to do with why he’s worth being interviewed. His value lies in the in-between moments, in the small conversations and interactions that he shares with the people he cares about. He’s a critical thinker, and I mean “critical” in the academic sense, like critiquing, AKA considering. He thinks about things and puts his thoughts together in novel ways and we’re all lucky that he spends a lot of time thinking about the people he interacts with. We benefit from his critical thinking because he mostly pays attention to other people. He looks you in the eye and thinks about what you say and connects the things he knows in new ways, and then he offers that as a suggestion, or a question, or simply an idea. He’ll never make money off it because that would preclude the honesty of it all. But it’s what makes him different. It’s what makes him worth writing about. It’s what makes him a great friend.

[Author’s Note: The title of this article and certain themes have been lifted wholesale from David Foster Wallace’s essay, How Tracy Austin Broke My Heart.]

Call for Comments (from Meghan)

Calling all Eric Senseman stories! Leave a comment to share your experiences with and stories about him.