Ian Torrence sits across the table from me and sips his beer. He dons the black-rimmed Smith glasses for which he’s become known. He wears a t-shirt from a race, and I don’t have to ask to know that it’s a race he’s either run, volunteered at, or race directed. He sports pants but, in his characteristic style, he rolls them up until they rest halfway up his shin. He’s visibly nervous, and confirms as much, because he knows he’ll have to talk about himself for the next hour.

“This makes me nervous. Put the recorder over there,” and he gestures toward the far end of the table. “I’d rather just talk to you.”

If you know or know of Torrence, then there are a few things you might already know about him.

You might know that he’s finished more than 200 ultramarathons since 1994. If you know him well, then he might admit to you that he’s finished exactly 203 of them—at the date of this article’s publishing; he’s still going, of course—and that he’s won more than 50 of those. You might know that he’s finished the JFK 50 Mile 22 times. You might know that he paced Hal Koerner to a Western States 100 win in 2009, or that he ran the 2011 TransRockies Run with two-time Western States winner and current course-record holder, Timothy Olson. You might know that he’s trained and raced with yet another Western States 100 winner—in this case a seven-time winner—Scott Jurek. You might also know that Karl Meltzer, a multi-time Hardrock 100 winner, asked Torrence to assist him during his speed record on the Appalachian Trail. And, if you know Torrence, you might know that all those people were at his wedding last May when he married Emily Torrence (neé Harrison).

Torrence on the homestretch of his 200th ultra finish at his beloved JFK 50 Mile in 2016. Photo: Geoffrey Scott Baker

But even if you know these things about Torrence, there’s probably a lot more that you don’t know.

You probably don’t know why he started running ultras, or about his vast ultrarunning friendship network. You may not be able to name a race that he’s won without hopping onto UltraSignup. You probably don’t know that he’s served as race director for at least eight different races over the years, or about the many other ways he gives back to the running community. But I think that these are the things people should know about a man who has spent the last 24 years—more than half his life—immersed in the ultrarunning community.

Torrence never won the Western States 100. (His best finish was eighth overall in 2002.) He never won the Hardrock 100. (He finished it once, in 2005, 13th overall). He never won the JFK 50 Mile. (He finished second, twice, in 2004 and 2005). Perhaps, as a result, he never rose to a level of fame that commanded the full attention of our sport. Perhaps, because attention makes him nervous, he avoids the limelight.

But for all his accomplishments, his bounty of experience and wisdom, and his positive influence on the sport in the forms of race directing, writing, and coaching, he deserves your attention.

I think you should read on.

Torrence and his now wife, Emily, having fun in Telluride, Colorado. All photos courtesy of Ian Torrence unless otherwise noted.

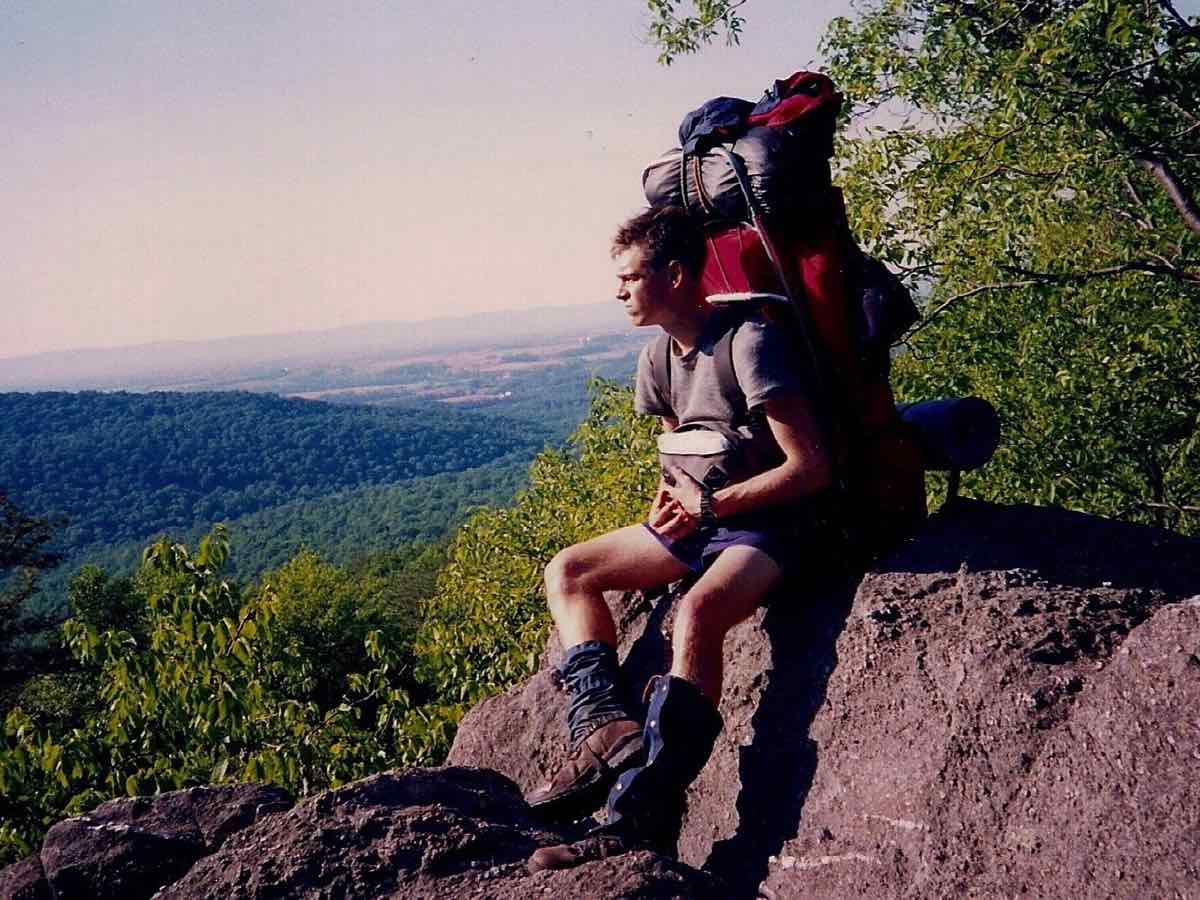

In the summer of 1994, two days after graduating from Allegheny College in Pennsylvania, a young Torrence set out on the Appalachian Trail (AT) at Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, just a 30-minute drive from his house. His backpack, which included most of what he would need for the next two months, was so large that it rose above his head. He had hiked in these mountains with his dad as a kid, and now he was hiking through them and beyond, all the way to the summit of Mount Katahdin in Maine, the AT’s northern terminus. He would hike roughly half of the long-distance trail in about two months, covering up to 30 miles in a day.

“I started doing ultras before I started doing ultras,” he reflects.

As a young man, Torrence hiked a large portion of the Appalachian Trail. In many ways, that adventure has shaped his life since.

While on the trail, he was told about a nearby ultramarathon, the JFK 50 Mile. It was run, in part, on this same trail, he was told. Having run cross country and track competitively for eight years through the end of college, in that moment on the trail Torrence had little interest in more competitive running. He didn’t think much about the race. But once he finished the AT and was back home, his competitive desire returned, and so he sought out information on nearby races. He had a half marathon in mind, but instead found a flyer for the JFK 50 Mile.

“Back in the day, there was no real internet. To find a race you went to an outdoors store and saw a flyer. I found a flyer for the JFK 50 Mile and I had a flashback to what those guys [on the trail] had told me. I set my sights on that,” remembers Torrence.

He would finish 12th that year. Within a few years of that 12th-place finish at JFK, Torrence’s ultrarunning career took off. He moved west, a dream of his since he was young, to explore wild places and open expanses. He became one of the best ultrarunners of his generation and friends with some of the sport’s brightest stars. He ran historic and competitive races all over the American west, like the Western States 100, Zane Grey 50 Mile, Angeles Crest 100 Mile, White River 50 Mile, and the American River 50 Mile.

At the age of 22, Torrence finished his first 100 miler: the Massanutten Mountain Trails 100 Mile Run, where he finished sixth. He would later win the race twice in 1999 and 2000.

And yet, nearly every year since 1994, Torrence has returned to the JFK 50 Mile. Its race director, Mike Spinnler, has said this much about Torrence and his impact on the country’s oldest continuously run ultramarathon:

“The JFK 50 Mile would not be what it is today without Ian Torrence. He brought energy and interest to the race when it needed it. And he kept coming back.”

His constant return speaks to his principles: he is loyal, grounded, and dedicated. It shows that he appreciates where he came from and how he got to someplace else. Torrence nearly tears up as he tries to describe his connection with JFK, “There’re a lot of connections. I learned how to backpack in those mountains with my dad. As a child I hiked there. I hiked a big portion of the AT that started near there. You put the locality of where I grew up—which was right [near the JFK course]—and the race director of JFK, and the type of event it is, and how big it is.”

Before Torrence moved west and as his ultrarunning career started to take shape, he established a foothold with the Virginia Happy Trail Running Club, which he marks as a helpful and influential link. With VHTRC, he learned from the legendary Scott Mills and got to know Chris Scott.

Torrence moved to southern Nevada to work for the National Park Service, eventually becoming a wildland firefighter. While he didn’t move to that region for ultrarunning purposes, per se, he started racing in southern California and got to know folks like Tom Nielsen and Hal Winton.

“That was a dream before ultrarunning was a thing for me: wide-open spaces, mountains to climb, shit to explore! I got a job through the [National] Park Service in Las Vegas. Then I found this huge community of people in that area who were, at the time, ripping shit up,” Torrence explains.

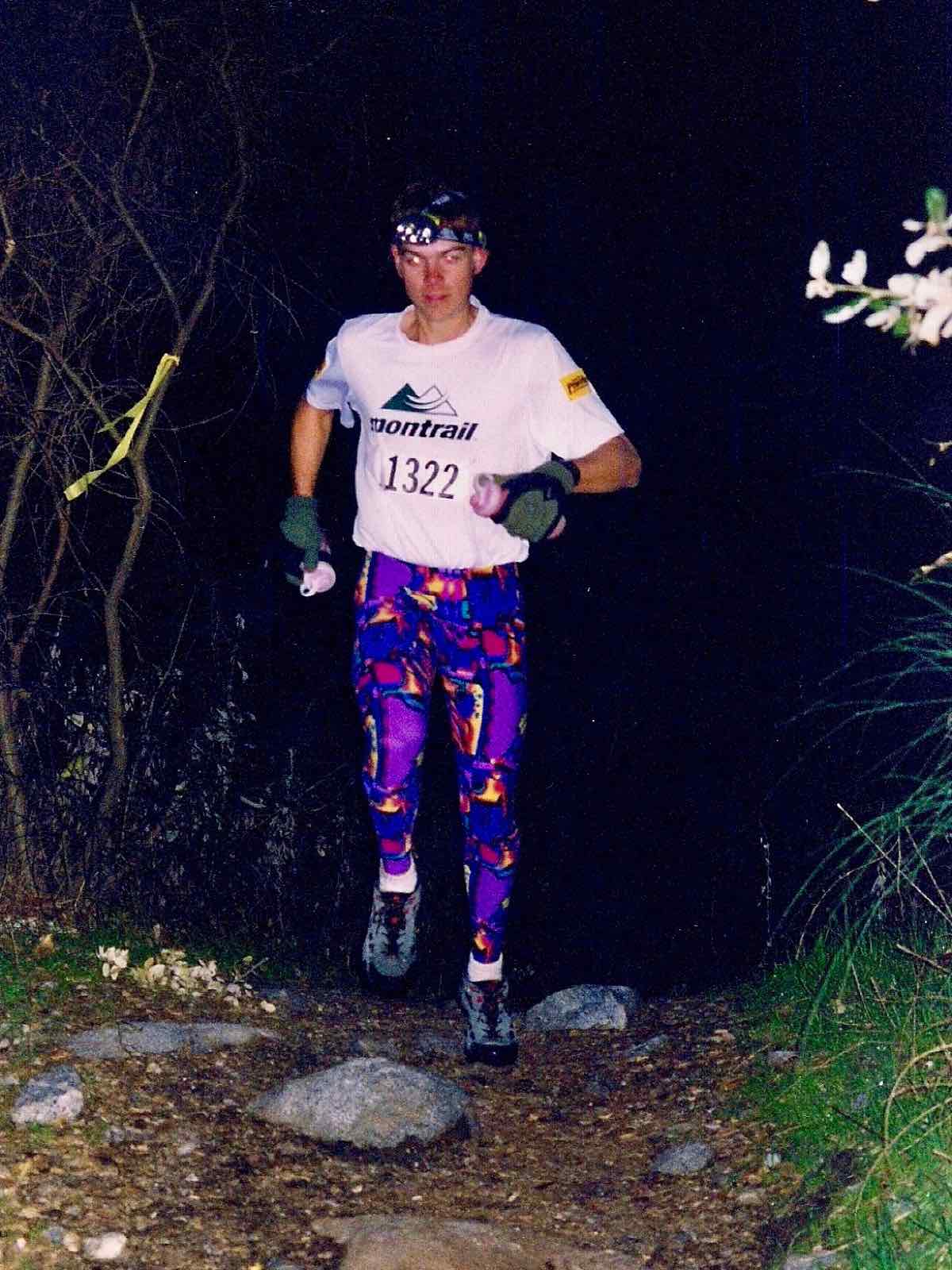

In 1998, during his stint in Vegas, Torrence ventured to Vermont to run the Vermont 100 Mile. Sitting in his car after the race, he heard a knock on his window. It was Scott McCoubrey, who worked for the Montrail shoe company then.

“Hey, you want to try these [Montrail] shoes?” McCoubrey asked.

Torrence was soon a Montrail athlete.

A few years ago, McCoubrey recounted to me his version of this story. Working for Montrail, he had heard of Torrence and was trying to put an athlete team together. He didn’t know how to get ahold of Torrence, but he knew he was running the Vermont 100 Mile. As McCoubrey told the story, he flew to Vermont in order to track him down at the race. I mentioned this to Torrence as we spoke.

“That’s awkward [laughs graciously]. I didn’t know that. I think he sought me out because of my age, my youth, and I had won a few races,” Torrence offered.

A few years later, McCoubrey was leaving Montrail to start the Seattle Running Company. Torrence was offered a job there and relocated to Seattle, Washington. It was in Seattle that he met Jurek.

“If you had the opportunity to go to Seattle at that time and work for Montrail and go to races to talk to people about shoes, would you do it? You give an ultrarunner—any ultrarunner—today that opportunity, and they probably say yes. It was a special time in the sport because it was small, yet the enthusiasm was so big that the opportunities existed. I don’t know, man—it was all lucky. I’m glad I was part of it.”

The next stop for Torrence, in 2007, was Ashland, Oregon—an ultrarunning hotbed filled with people like Koerner, Olson, Erik Skaggs, and Tony Krupicka. Torrence’s motivations were simple.

“I went to those places because there were people there who were influential. The timing was right, and it was okay to do that. I didn’t move to these places solely for running, although it was a major factor. There were people in those locations that drew me there. With Ashland, I asked Hal [Koerner] if I could work at his store and run with him, basically.”

After soaking it all up in Nevada, Washington, and Oregon, Torrence found one more place to call home: Flagstaff, Arizona. He still lives there, and it’s where Torrence has put all his years of learning to work by giving back what ultrarunning has given him.

It can be easily argued that, to a large degree, running is a selfish endeavor. When we choose to run, and to run far, we do it because, at least on some level, we enjoy it. To finish more than 200 ultramarathons, as Torrence has, enjoyment is part of the equation.

“I like the sport, I like where the races take you. New territory, new places to explore. I’ve done a lot of races that way. There’s a part of me that is competitive and that wants to race like I’m 23 again, but another part of me knows I can’t do that anymore. Either way, whether you’re first or last, racing 50 miles is a huge accomplishment. Not many people do that in today’s society. Ultrarunning is a growing sport, but ultrarunners are definitely the minority,” he explains.

Torrence will run ultras as long as he can. But whether he can run or not, I think he will always be involved in the ultrarunning community. And involvement in the sport beyond simply running races shows a significant degree of selflessness. It shows a commitment and dedication beyond your own interests. It tells us, like his continuous return to the JFK 50 Mile, where Torrence’s values lie.

Since moving to Flagstaff about eight years ago, Torrence has taken to writing—notably, as an iRunFar columnist; coaching—with his wife through their company, Sundog Running; and race directing—some eight-plus races in the Southwest over the years, including his Flagstaff to Grand Canyon Stagecoach Line Runs. He does all of this aside from his full-time job for the American Conservation Experience, which performs restoration work on ecosystems throughout the Southwest. I asked Torrence why he would engage in so much extra work outside of his day job:

“[Race directors] create a small village. It’s a community. Everyone is trying to help everyone else. It’s this cool, cyclical pattern that develops. It’s local people helping local people. I think it brings about community and people really rally around that. You can make a place special that way. Even if you’re not winning anymore, but you still care for the sport, then you write, or you coach, or you direct a race. Doing it for reasons that are whole and not selfish. I just like the sport. I like the people. I’ve met a lot of cool people doing it. Hopefully we can perpetuate that.”

At the conclusion of his Flagstaff to Grand Canyon Stagecoach Line Runs, Torrence thanks a finisher. Photo: Melissa Ruse

Torrence spent years of his life moving from place to place because of the people that were there and the communities they formed. Now, in Flagstaff, he’s helping to create a community that others seek out and enjoy. The cycle about which he speaks circles on. The town, the JFK 50 Mile, and the ultrarunning community at large is different—and better—because of him.

If you know Ian Torrence, then this is what you should know about him.

Call for Comments (from Meghan)

Calling all Ian Torrence stories! Yeah, we know they are out there. :) Running and racing, road tripping and camping, participating in one of his races, if you have a story, leave a comment to share it. Thank you!