[Editor’s Note: iRunFar contributor Morgan Williams sustained severe injuries in a fall while trail running in June of 2016. He wrote about the injury in a narrative last year. In this essay, he narrates his continued recovery and his evolving relationship with running.]

Four hundred and eighty-five days. Since I ran. Since I fell. Since I slipped or tripped running fast downhill, landed on my left leg in full extension, suffered an eight-break tibial-plateau fracture, twisted violently and ruptured both my anterior cruciate and posterior cruciate ligaments, and then landed heavily on my right shoulder and broke my collarbone. I never do anything by halves…

Toward the end of my first meeting with the consultant surgeon, me in the prone position with the left leg in plaster from groin to big toe, he said: “I’m afraid you won’t run on that knee again Mr. Williams.” So, when in early November of 2017 the physiotherapist suggests I go outside into the car park to run, it should be a critical moment. It doesn’t feel like that though. In truth, I’m not sure how it feels, how to react. Afterward, I conclude that it’s just another part of the recovery, another step on the road to somewhere new. My new, unexpected relationship with running.

***

In July of 2017, my wife Alison and I finally move ‘home’ after 18 months of effort; away from the urban environment in which we have lived for many years. Our new home is in a farming hamlet of 24 dwellings in the southern tip of the Yorkshire Dales National Park in England. The landscape is rolling rather than mountainous. We are delighted by the new sense of space. Our previous home was in a small town of 15,000 people nestling under a famous expanse of heathery upland we call moor. We hadn’t realised how the moor, even at the relatively lowly height of 1,400 feet, restricted our view, and the expansive views are refreshing. Some evenings on my drive home from work I have to stop the van, step out, and photograph the landscape.

The quiet is exhilarating. We soon learn the different reaction of the human body to being awakened in the small hours by natural sounds as opposed to the inebriated ramblings of neighbours’ teenage children. When we are awakened by the hooting of the barn owl or the mewing ‘piiiyay’ of the buzzard, sleep returns quickly.

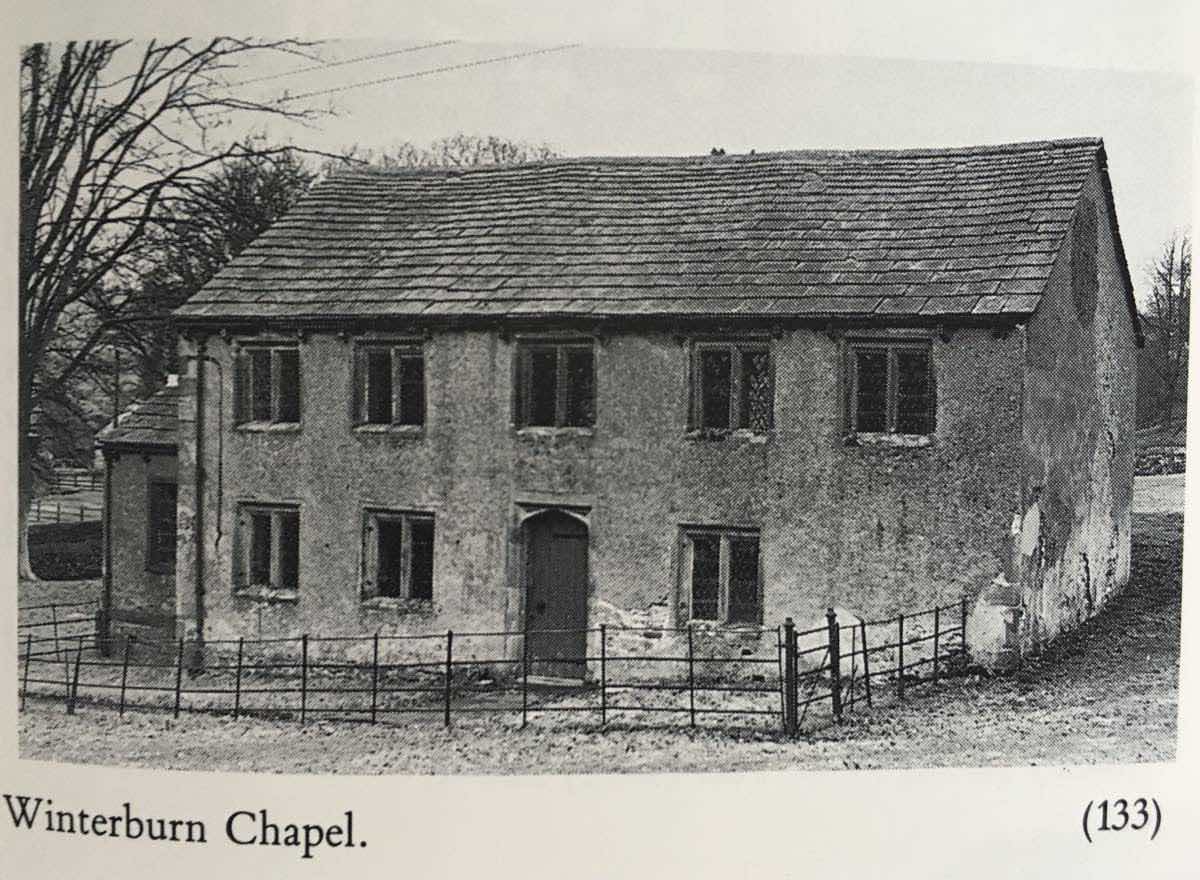

Our new home nestles perfectly into the landscape. It has been there for a long time. A small slice of English history. The Chapel House, as it is officially called, was one of the earliest nonconformist chapels in England in use from 1703[1]. The Toleration Act of 1689 was one of the most significant religious reforms in England following its break with the Catholic Church. The Act exempted religious dissenters from certain penalties and disadvantages under which they had suffered for more than a century. Nonconformists were, after 1689, finally allowed their own places of worship.

Alison and I aren’t religious people, but living with the ghosts of nonconformists feels very right somehow. And our home has a good feeling that comes with a building that has had constant human interaction for more than 300 years. A wonderful place to repair, recover, and live.

***

One hundred and forty-five degrees. Of knee flexion. On a good day. On a warm day. On a cold day, probably closer to 135. The flexion has been stuck at that level for 10 weeks or so now. The physio suggests we call it done at that. Time to concentrate on other aspects of the recovery. Healthy knees flex somewhere between 155 and 160 degrees. It doesn’t sound like much difference. In reality, this translates to a gap of around 12 or 13 centimetres between my butt and my left heel. The left knee will never be fully functional. It’s not life-changing, but life has changed as a result of the damage done.

“Can you empty those boxes of books and put them onto the bookshelves in your study?” It’s a simple-enough request from Alison, a couple of weeks after we move. When I come to start the task of putting the books on a lower shelf, I pause, having to think about how to get my body down there. I can kneel, but not for long because there is significant nerve damage in the patellar area. And I can’t squat down on my haunches because my knee lacks the requisite flex. It takes a few minutes to figure out how best to do the job. I nip next door to the lounge and borrow Alison’s meditation cushion. I want to sit on this to get me about eight inches off the floor. Inevitably, on my first attempt to drop onto the cushion, I misjudge my positioning and balance, flip sideways onto the floor, and lie there giggling. This sort of minor mishap is a regular feature of home life now. You have to laugh.

***

6 November 2017; the day I first ran again. I’m following the National Health Service’s Couch to 5K programme. We’ve all been there, coming back to running from injuries, or ailments of various degrees. This time though, it’s especially humbling. Like many others in our little world, I used to run whenever I wanted for as long as I wanted on whatever surface I fancied. By week four I’m up to repetitions of four minutes of continuous running interspersed with walking, on tarmac. There is as yet no joy in this; no strength, no power, no elegance. I’m doing it because I have been asked to as part of my recovery. When I run, the knee dominates me mentally. There is no relaxation. I recall the surgeon telling me to plan for a 30-month recovery period to reach my “new normal.” I’m only 18 months into that period. Things will improve, I’m convinced. Patience is key.

***

If I leave the Chapel, cross the cattle grid, and turn right, a ribbon of tarmac takes me up the Winterburn valley to a reservoir. Built around 1880, the reservoir feeds the Leeds to Liverpool Canal. This fine construction, primarily the work of the famous engineer James Brindley, was started on 5 November 1770 and connects the former industrial and textile centre of West Yorkshire, in the shape of the city of Leeds, with the port city of Liverpool on the country’s west coast. It is a mile each way to the water. Long before running features again in my life, I commit to making the journey up the road, walking, as often as I can. Most days I make the trip, whatever the weather.

It’s not an especially inspiring walk or run. Much of the valley is hemmed in by mature forest, a mix of various pines, firs, and deciduous trees planted not long after the reservoir was completed by the Victorian estate owners. But the view opens out as the reservoir is reached and the greeny-brown expanses of Winterburn and Hetton Moors, low-lying, undramatic, and yet still life-affirming, come into view.

This slender strip of tarmac, winding its way up to the water, has unexpectedly become a key part of my life and recovery. Every trip up and down is a lesson in the natural world. I’ve begun to see the little things. I’ve watched the changing of the landscape over the months and learnt many things about the trees, the livestock dotted around, and the prevailing weather conditions. Best of all I have become familiar with the wild creatures that make their homes here; the antics of the crows and gulls that are so numerous; the roe deer that live in the forest; the two majestic pairs of grey herons that live in and around Winterburn Beck, the not-quite-a-river-yet-more-than-a-stream watercourse that flows close to our home and that connects the reservoir with the River Aire; the pair of buzzards that nest close by and rise and fall with the thermals.

A walk up to the water feels incomplete without a sighting of one of the herons or the buzzards or hopefully, both. They have become talismans. Doctor Doolittle-like, I’m talking to the animals and birds. After months of traveling up and down, I’m now coming within about 30 feet of the herons before they take off and move up- or down-stream. It’s like I’m becoming part of the landscape.

***

“Does it still hurt?” is the most often asked question. The answer is, yes it does. Not just the plated knee, but the plated collarbone also. All day. Every waking minute. Not enough to require pain-relief medication. But enough that a couple of pints of strong beer have no effect. I wonder if I’ll ever get used to it. Things are marginally better after an active day, rather than a day behind the desk at work. Without fail, active day or work day, by mid-afternoon my knee feels like it has been filled with concrete. The cruciate ligaments and the hamstring tendon, from which tissue to repair the cruciates was borrowed, feel like bass-note piano wires. I maintain hope that by month 30 the discomfort will have reduced to a level where I can forget about it for at least part of each day. Patience.

***

May 2017 of brings a good moment. iRunFar’s Meghan and Bryon are in England. We host them at the old home for a night on their way north. Meghan gets some miles and vertical in on Ilkley Moor. Bryon and I get out for a walk to help him ease back into things after his Thames Path 100 Mile (with beer stops I recall…) and potter around looking at numerous cup and ring rock carvings from the Bronze Age anywhere up to 4,000 years old[2].

Then they shoot further north to the Lakes to start Meghan’s preparation for her attempt on the Bob Graham Round. Meghan records her successful attempt in this article.

Bob Graham days are always intense and Meghan’s day was no exception. Alison and I were ‘between’ campervans and made do with the car for support, not least because Wynn and Steve Cliff were on hand with their campervan. I had no idea how I would hold up during the full day and a bit, as the after-effects of the accident and two major surgeries were still in my system.

Happily, it all went rather well, as Meghan’s own write-up records. I had hatched a plan to try and meet Meghan on her 40th of 42 peaks, Dale Head, which is a relatively easy walk-up from the final major road-crossing/crew point at Honister Pass, which marks the end of the round’s Leg 4 and the beginning of Leg 5. Getting the timing right is difficult on Legs 4 and 5. There is no phone service at Wasdale Head (the crew point between Legs 3 and 4) or at Honister. If you are lucky, one of the on-the-fell support team members will send the occasional text to report on progress during Leg 4, which you pick up while en route to the start of Leg 5. So, it is pure guesswork on our part as to the timing of our departure up the hill so as to hopefully meet Meghan on the summit.

Dusk is drawing in as Alison and I set off, buoyed by the magnificent sunset we had seen from the pass, a real rarity at the often-bleak Honister. Armed with my trusty wizard sticks and hiking boots, and with Alison for company, I set out for my first mountain summit in almost 12 months. Like Meghan’s day, my small slice of action goes well. We reach the summit safely. Sadly, the weather deteriorates shortly after we arrive and my core starts to chill quickly. Post-accident I currently have a ‘no heroics’ rule, so we about-turn to make our way back to the pass and the car. We pass Meghan about halfway down, looking like a woman on a mission, if a touch worse for wear by then. About 59 miles and 26,500 feet of vertical gain will do that to you.

It’s an important day for me; a small achievement and another step along the bumpy road to recovery.

But in the weeks after Meghan’s Bob Graham Round attempt, I decide to relinquish the role of Secretary of the Bob Graham 24 Hour Club after 12 years. It’s clear to me that ultrarunning has no place in my future. The knee won’t stand that kind of abuse. I’ve always held the view that for a role where I occasionally have to ‘instruct’ people about their behaviour, being an active member of that community gives me at least a degree of moral authority to dish out the odd lecture. Now it’s someone else’s turn.

For many years acronyms have peppered my life: BG, CCC, UTSdT (the 110k Ultra Trail Serra de Tramuntana on Mallorca), UTMB. These efforts, all successful, played a major part in my life and are to be celebrated. They are good memories, are part of my past, and helped make me the person I am today, capable of dealing with the rigours of the recovery. It’s clear that I won’t get to do PTL or TdG, but there’s truly no sense of loss.

I do have aspirations. The first is a 5k Parkrun, joining the 100,000-plus people in the U.K. who run at 9.00 a.m. each Saturday morning[3]. That gets done on 20 January 2018. Not pretty. Not quick. But no alarms.

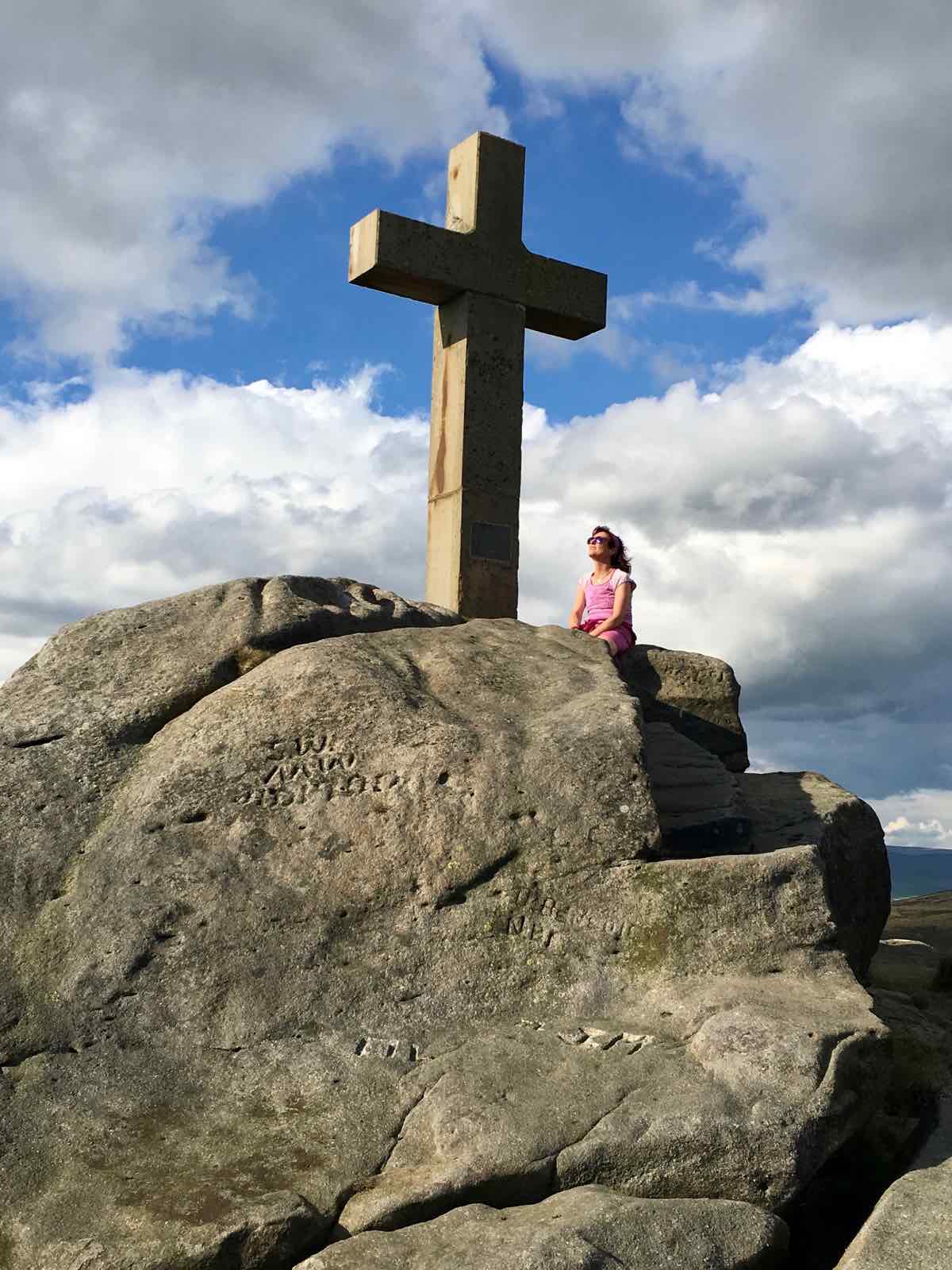

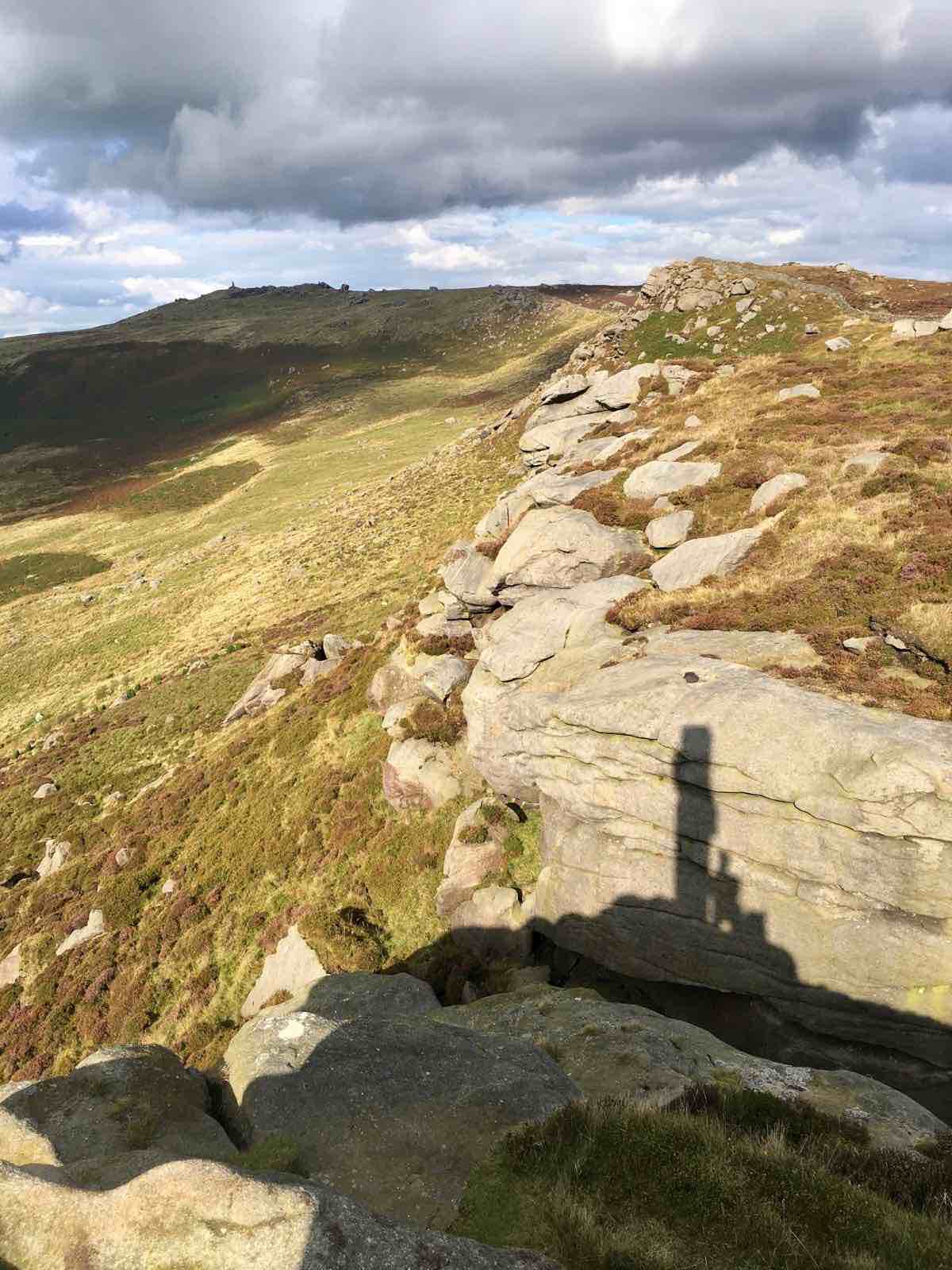

My dream is to run the beautiful rocky ridgeline a stone’s throw away from home, between the cross and the monument, as it twists above the gorgeous Dales villages of Rylstone and Cracoe. Six miles. I’ll leave that until warmer months when the ground is dry. After that, who knows?

By mid-February, I run for 49 minutes on gently rolling trails. Two days later, we do a six-mile walk in a loop around local hills. The ground is saturated, mud and water aplenty, and the boggy landscape sucks the life out of me. I realise that for now I have to choose my route, my weather, and my season with much more care. It becomes clear that at this point each effort drags a great deal out of me.

I run twice a week, maybe three times. The escape from the tyranny of the traning schedule is refreshing. My body (save for the damaged parts) doesn’t ache most of the time. I care nothing for the statistics of miles covered, feet ascended, hours on the feet. How I feel is the important thing. The experience, even in a 40-minute run, is everything.

And there is a frisson to every outing now. Every run could be my last. That’s no drama though; because I already did my last run… on 8 July 2016. Or so the surgeon said.

***

October of 2017 finds Alison and I in Nepal. We are there to help dig the foundations for a new three-storey classroom block at a secondary school on the outskirts of Kathmandu. The old block collapsed in the 2015 earthquake, fortunately when the children were elsewhere. Five days of physical work. Pick axes, shovels, wheelbarrows, vast quantities of sand, gravel, bricks. A site inaccessible to vehicles or heavy equipment. The knee and the shoulder come through the week without mishap and more confidence is squirreled away. Most importantly, friends are made and promises made to return.

We have a few days in and around Kathmandu once the work is done and find ourselves hiking up a tarmac road at 5:00 a.m. one chilly autumn morning to watch the sun rise over the Himalaya.

It’s a spectacular sight because the morning is clear. Surprisingly, I find myself drawn not so much by the view to the high peaks, rather by the view eastward into a lower, less dramatic landscape, spectacularly illuminated by the rising sun; an incredible landskein. It’s an intriguing moment and I wonder if there is any symbolism in my turning away from the snowy mountains.

***

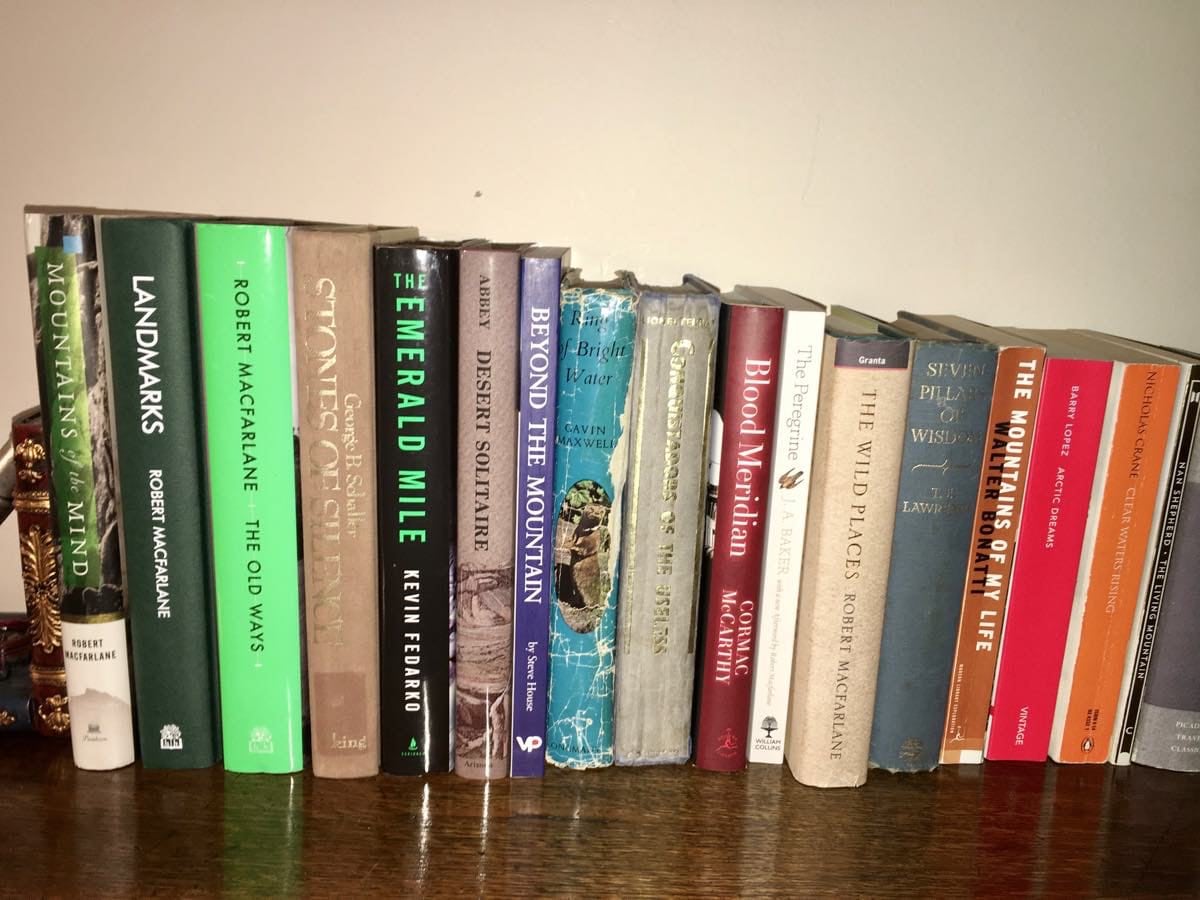

A lot less time spent running has made time for other things. I have been reading; a lot. Strangely perhaps, I haven’t read a book about running since the accident. Whisper it, I’m even spending less time on iRunFar. The natural world has featured strongly. Robert Macfarlane, Gavin Maxwell, Lyall Watson, Jim Crumley, George Schaller, Edward Abbey, Barry Lopez, Nan Shepherd, J. A. Baker. Two books in particular have become bellwether works, delighting and enlightening: Macfarlane’s The Old Ways and Baker’s The Peregrine.

Records reveal that at its peak, the Chapel, our home now, had a congregation of around 65 people and that many of them walked distances of up to seven miles to get here. The Old Ways, in particular, (a “book that could not have been written by sitting still”[4]) triggers thoughts and questions. I’m becoming fascinated by thoughts of where they lived and how they traveled from their homes to the Chapel. Which roads, which paths? Did they make their way cross country? How long did it take them to get here? A personal quest perhaps for me to turn to in time. It’s no surprise this beautiful building gives off an air of contentment; it was journey’s end.

My journey continues. Life is changing. It’s not better or worse. It’s simply different.

Call for Comments (from Meghan)

- If you are someone who has experienced a major health issue, how has your relationship with running evolved? Has your fitness helped you recover? Does the hope of returning to running help or have you had to intentionally turn away from it at least in part?

- If you are a runner who can’t or doesn’t run as much as you used to, have you been able to take up walking, hiking, biking, or other forms of movement? What is your relationship with these new-to-you sports like?

Footnotes

[1] Nonconformist Chapels and Meeting Houses in the North of England, HMSO, 1994 page 250

[2] https://www.ilkleymoor.org/discovering-ilkley-moor/archaeology/

[3] https://www.parkrun.org.uk

[4] The Old Ways, Robert Macfarlane, Hamish Hamilton 2012, Author’s note