[Editor’s Note: This article was written by the Trail Sisters’ Liza Howard.]

Except for an emergency appendectomy in second grade, I was a healthy kid.

And besides being ancient when I had my own kids, I have no medical history to speak of. I’d draw a long line down the ‘No’ column of patient-history forms. At annual physicals, I’d apologize for being so medically dull, and look for openings to mention my lost appendix.

“Diabetes?”

“No.”

“High blood pressure?”

“Nope.”

“Emphysema?”

“Not even a little.”

“Allergies?”

“Sorry, not one.”

“Coronary artery disease?”

“Again, sorry, no.”

“Ulcers?”

“Well, no. BUT I did have my appendix out in second grade! I missed Halloween. I was going to be Snow White and wear real makeup. I was devastated.”

All this is to say, I was healthy, and I was used to my body cooperating with my plans for it. As a result, it took me almost two years to recognize I was struggling with asthma.

Hi, my name is Liza, and I’m an asthmatic ultrarunner.

The asthmatic runner is easily identifiable by his or her red rescue inhaler. All photos courtesy of Liza Howard unless otherwise noted.

When I proposed writing about asthma to the other Trail Sisters, Pam Smith and Gina Lucrezi, and our editor, Meghan Hicks, I envisioned writing something with an inspiring Cinderella arc. I’d start with a description of myself, bronchoconstricted and ready to give up running, lying defeated under a pile of leaves at the JFK 50 Mile last November.

And I’d end the article with a vivid account of standing on a podium having finally knocked out a qualifying time for the U.S. 100k team. My asthmatic sisters and brothers would take heart. Chronic lung diseased be damned! With the right combination of medications, patience, and training, anything was possible. And those of you without drama-queen lungs would embrace my broader message about vision and action, and self-awareness–because all that had clearly paid off. And there’d be lots of spit-your-coffee-out funny stories about my missteps during the asthmatic journey. (‘Cuz that’s how I roll.)

But I’m nowhere near the happily-ever-after part of the story. I’m maybe two-thirds into the fairy tale, tops–just after Cinderella returns home from the ball and is back to scouring floors. And there’s no sign that any princely pulmonologist is looking for me.

In my case, the floor scouring involves dragging a chair over to the kid-safe cupboard above the stove every morning, pulling down two inhalers and a bottle of Singulair, reminding myself to be thankful for medical insurance, washing the Singulair pill down with coffee, and ‘squeezing and breathing’ on the inhalers. That regimen allows me to run for about three hours without trouble. After three hours, my lungs turn into pumpkins and I feel like I’m breathing through a straw.

How to Simulate Asthma Symptoms

If you don’t have asthma and you want to experience the symptoms, grab a straw and stand somewhere you can jog in place. Jog for 30 seconds and then breathe through the straw while pinching your nostrils shut.

Nice, eh? Hard to PR like that.

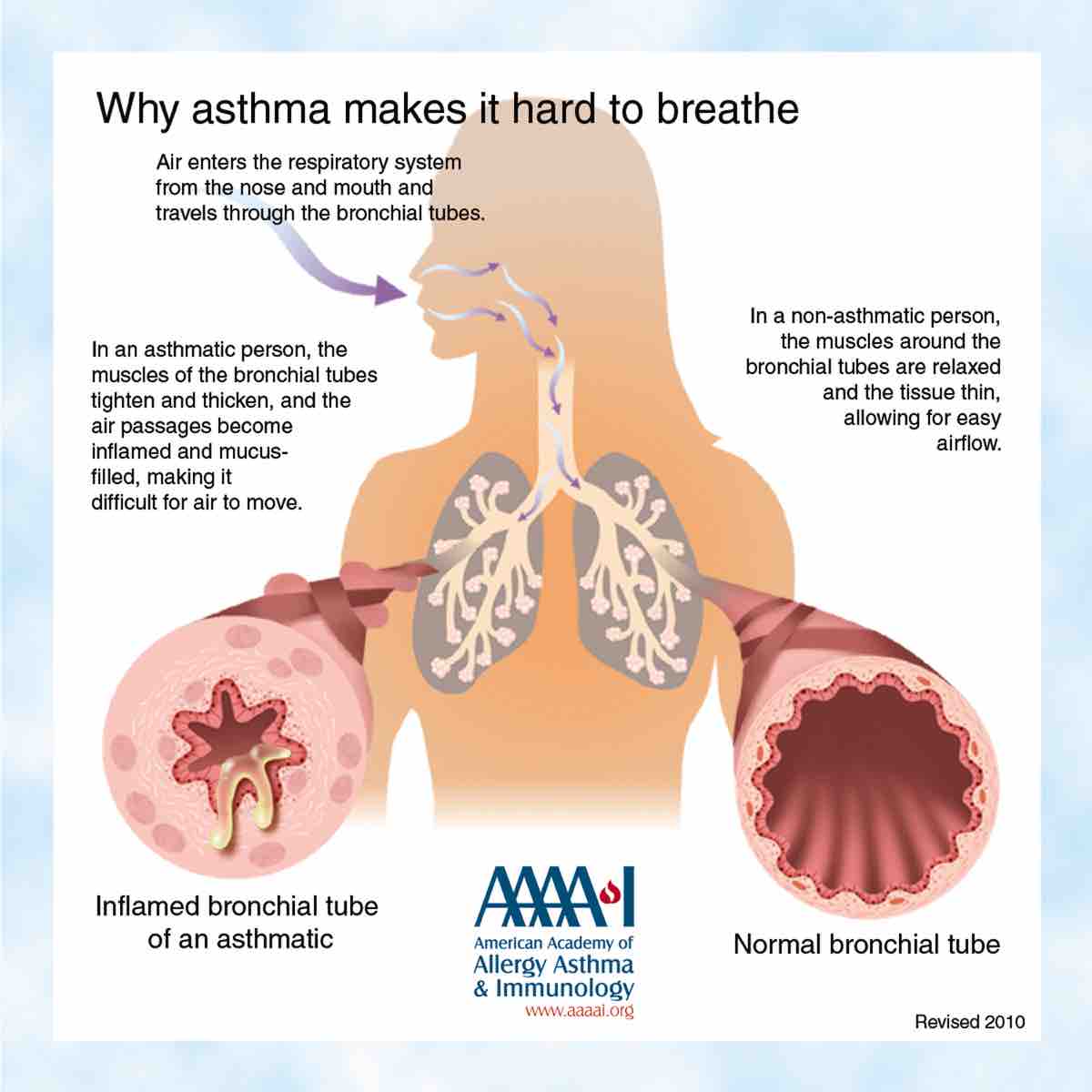

Us asthmatics get that tight-chested, air-hungry feeling when the muscles around our small airway passages (bronchioles) tighten. When someone says they’re having an asthma attack, this is what’s going on. (‘Bronchoconstriction’ for you Scrabble players.) And there are a great many things that can trigger an asthma attack. Dust, mold, scented cleaning products, cat dander, aspirin, cold air, stress, exercise… Basically anything. For me, it seems like sand, dust, cold air, altitude, and exercise are strong triggers. You know, trail running things.

I was in full breathing-through-a-straw mode by the time I made it to the mile-45 aid station at the Lake Sonoma 50 Mile last month. I hid behind a tree to use my rescue inhaler. (I would definitely be that choking person who gets up from the restaurant table, embarrassed, and then passes out alone in the restroom.)

Rescue inhalers contain fast-acting bronchodilators. They increase the diameter of the airway passages and make you feel like you’re not breathing through a straw anymore. Right now, my doctor has me using this inhaler 20 minutes before a run and every two hours during the run. I carry it in the top pocket of my hydration pack.

How to Use a Rescue Inhaler

For you uninitiated, you have to suck the aerosolized medication deep into your lungs for it to work. To accomplish this:

- Exhale until you can’t exhale any more and you really want to inhale.

- Put your lips around the inhaler’s mouthpiece.

- Depress the inhaler while inhaling deeply (to move the medication to the littlest airway passages in your lungs).

- Hold your breath for 10 seconds (to make sure you don’t just exhale the medication).

Most folks are instructed to take two puffs of medication, about a minute apart.

But here’s the deal, asthma isn’t just bronchoconstriction. There are three things going on in an asthmatic’s lungs that impede airflow and running PRs.

- Narrowed airway passages (bronchoconstriction)

- Inflamed airway passages

- Increased mucus production in the airway passages (Whee!!)

When I teach about asthma for NOLS Wilderness Medicine, I always feel like I’m doing a strange infomercial.

“NOT ONLY DO YOU GET BRONCHOCONSTRICTION, YOU ALSO GET INFLAMMATION!! BUT WAIT, THERE’S MORE! WE’LL ALSO THROW IN SOME MUCUS TO PLUG UP THOSE AIRWAY PASSAGES!!!”

And a rescue inhaler doesn’t touch the inflammation and mucus. Gargh!

Long-term control medications are necessary for that. And figuring out exactly what those medications should be isn’t easy. It’s like blister prevention. What works for one person might not work for somebody else. And what works in one environment might not work in another.

That’s where I am right now. I’ve tried four different kinds of anti-inflammatories and anti-inflammatory combinations. The first medication helped a bit. The second and third helped a bit more. I went from jogging to being able to run at marathon pace from time to time. I still felt really fatigued on most runs, though, like I was wearing a weight vest. And I couldn’t always hold a good pace. The asthma doctor threw up his hands at that point and referred me to a pulmonologist. “I don’t know why you’re not responding. Maybe it’s your heart.” (Spoiler: It’s not.)

Unfortunately, the punt to the pulmonologist hasn’t maximized my field position much. It’s my fault. I answered her question about why I’d come to see her with: “I can only run for three hours before I need to use a rescue inhaler.” Her eyes actually glazed over. I tried to rephrase things so I didn’t sound like a privileged lunatic, but she just looked more and more like she was powering off.

“When I was in the Sahara Desert running this multi-day race, my heart rate was just so high…”

“At this 50-mile race, I was really short of breath…”

“You get belt buckles when you finish these races–and I used to do really well.”

“Training just feels harder than it should…”

Honestly, if I hadn’t had a back-from-the-dead experience at the JFK 50 Mile, I would have been entirely cowed by the pulmonologist’s disinterest. I would have stopped running ultras, made my peace with recreational jogging, and looked for other ways to occupy my time–like blogging about donut eating.

But at JFK, after feeling like I was jogging through chest-deep water for hours and multiple hits on the rescue inhaler, a cold front moved in around mile 38. The wind kicked up, the temperature dropped 20 degrees Fahrenheit, and it began to rain.

And I was transformed.

I went from walking at a 30-minute-mile pace to racing. I felt like my old self! I ran the last eight miles almost as fast as the winning women. (Obviously that doesn’t mean I could run anything close to their 50-mile times. They were running hard the whole race while I took breaks, lying on the ground feeling sorry for myself.) But the night-and-day difference I felt when the weather changed filled me with hope. There had to be some medication or approach that would have the same miracle-like effect.

That faith got me through the appointment with the dismissive pulmonologist. And it’s kept me from despair and donuts. I just need to find the right lung doctor–someone excited to work with an old-lady runner who still has a big appetite for belt buckles and dreams of being on the U.S. 100k team, a niche miracle worker who accepts BlueCross BlueShield insurance.

I’ve signed up for JFK again this November. I need to run a sub-7:15 there to qualify for the 2018 100k team. If I do, it’ll be the perfect happily-ever-after ending to Part 2 of this article. In Part 2, which I plan to write in December, I’ll write about how things have progressed with me, how other runners cope with asthma, and issues surrounding asthma medications that are on the World Anti-Doping Agency’s Prohibited List.

But just in case I’m not meant to be Cinderella, and I–or any other runner–walk into an aid station you’re volunteering at and tell you I can’t catch my breath or my chest is tight, I’d be grateful if you followed this checklist.

How to Help a Runner Having an Asthma Attack

- Crack open a can of calm. (Stress is a trigger. The more upset I am, the harder it will be to relieve the symptoms.)

- Ask me if I have my inhaler, and help me get it if I do.

- Ask me if I know what triggered the attack. Remove that trigger if you can.

- Tell me to purse my lips like I’m playing the trumpet and breathe that way. (The back pressure created can make it easier to breathe. It also slows breathing, which has a calming effect.)

- Make sure I’m hydrated to keep the mucus loose. (Loose mucus!)

- Remind me not to take any ibuprofen or Tylenol or other non-steroidal anti-inflammatories. (They can make the attack worse.)

- Don’t let me keep running until I feel better.

- Take me to get medical attention if what usually makes things better isn’t working. (Make sure to take anyone who’s having a first-time asthma attack.)

Call for Comments (from Liza)

Asthmatic sisters and brothers, I’d love to hear your stories–Cinderella or otherwise. I’d like to include some of your experiences running with asthma in December’s Part 2 of this article. Please comment below. (Pam, of the Trail Sisters, is also in the asthmatic ultrarunner family.)