[Editor’s Note: This article includes reports from select presentations given during the 2017 International Congress on Medicine & Science in Ultra-Endurance Sports on May 30, 2017 organized by The Foundation for Ultra Sports Science. Be sure to check out all the presentation abstracts, which are based on yet-to-be published research. For those attending the 2017 Western States 100 in person next week, note that Dr. Høeg and others will be presenting on Thursday afternoon in Squaw Valley, California on emergent ultrarunning-related research.]

[Editor’s Note: This article includes reports from select presentations given during the 2017 International Congress on Medicine & Science in Ultra-Endurance Sports on May 30, 2017 organized by The Foundation for Ultra Sports Science. Be sure to check out all the presentation abstracts, which are based on yet-to-be published research. For those attending the 2017 Western States 100 in person next week, note that Dr. Høeg and others will be presenting on Thursday afternoon in Squaw Valley, California on emergent ultrarunning-related research.]

Determinants of Recovery

Martin D Hoffman, MD, FACSM, Professor of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, University of California Davis and Chief, Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, VA Northern California Health Care System (and program director of this conference)

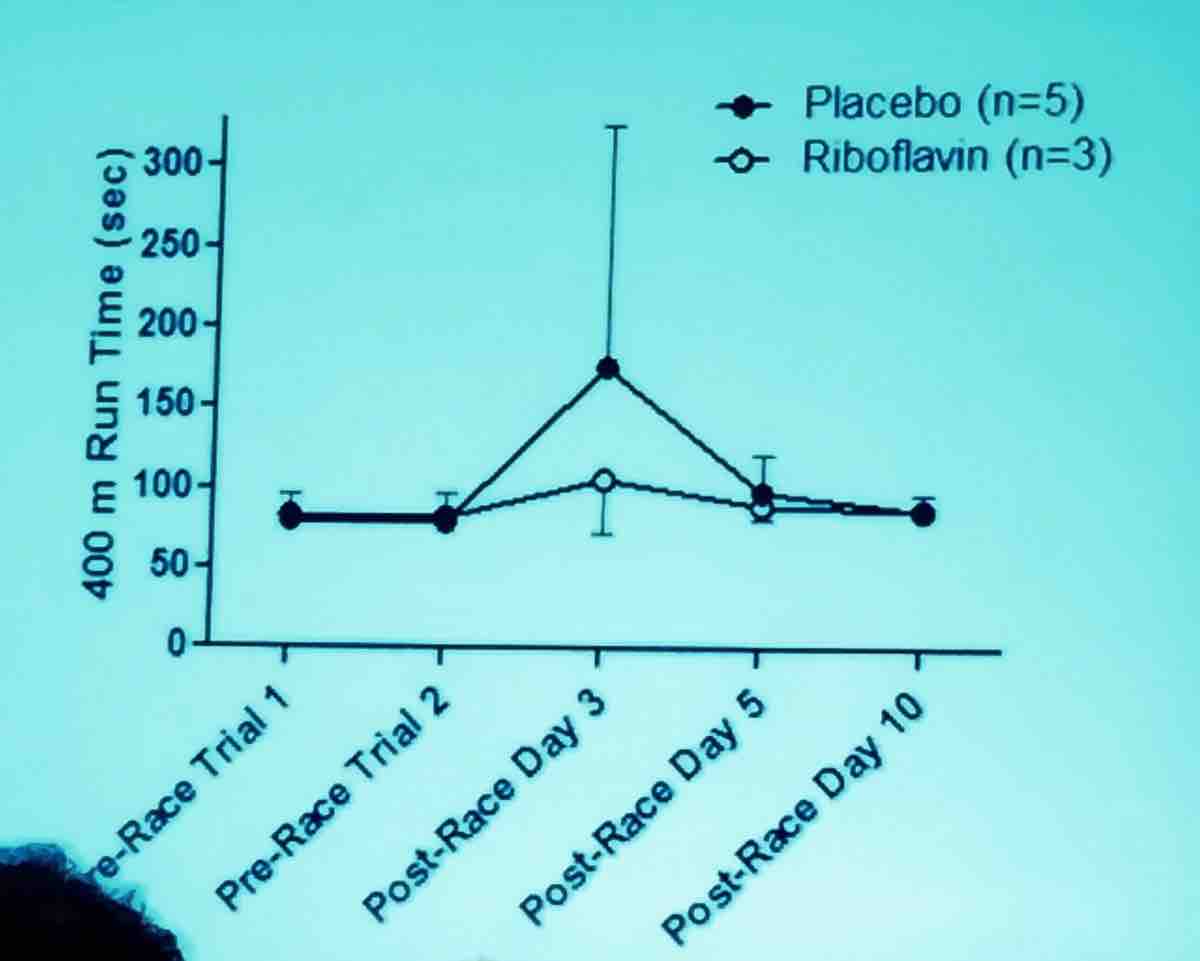

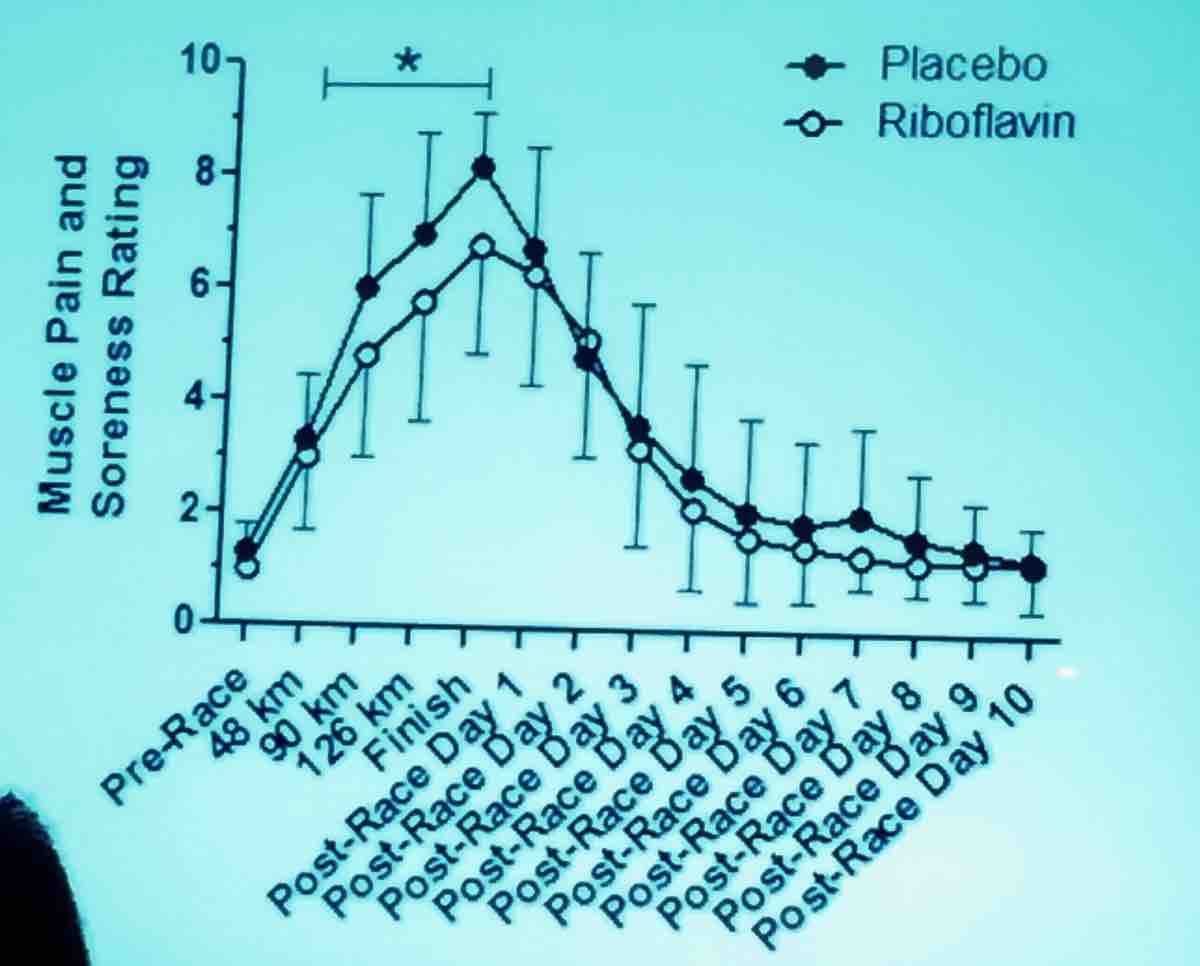

Data from the 2016 Western States 100 looked at return to baseline to 400-meter run speed following running the 100-mile race and it took around 10 days for runners to return to their baseline 400-meter speed, but subjectively they thought they were recovered at about five days. As you can see below, runners who received riboflavin* versus a control recovered significantly faster in terms of 400-meter speed.

Also, female sex, longer pre-race training runs, and higher post-race creatine phosphokinase were all associated with faster recovery times. Probably even more interesting is the fact that runners who unwittingly received riboflavin pre-race and at the midway point reported less pain and soreness during the race and at the finish line (which was statistically significantly different) compared with those who received placebo.

*riboflavin (B2): 100 milligrams riboflavin before the race and halfway through. Placebo at same times, which contained a small amount of beta-carotene.

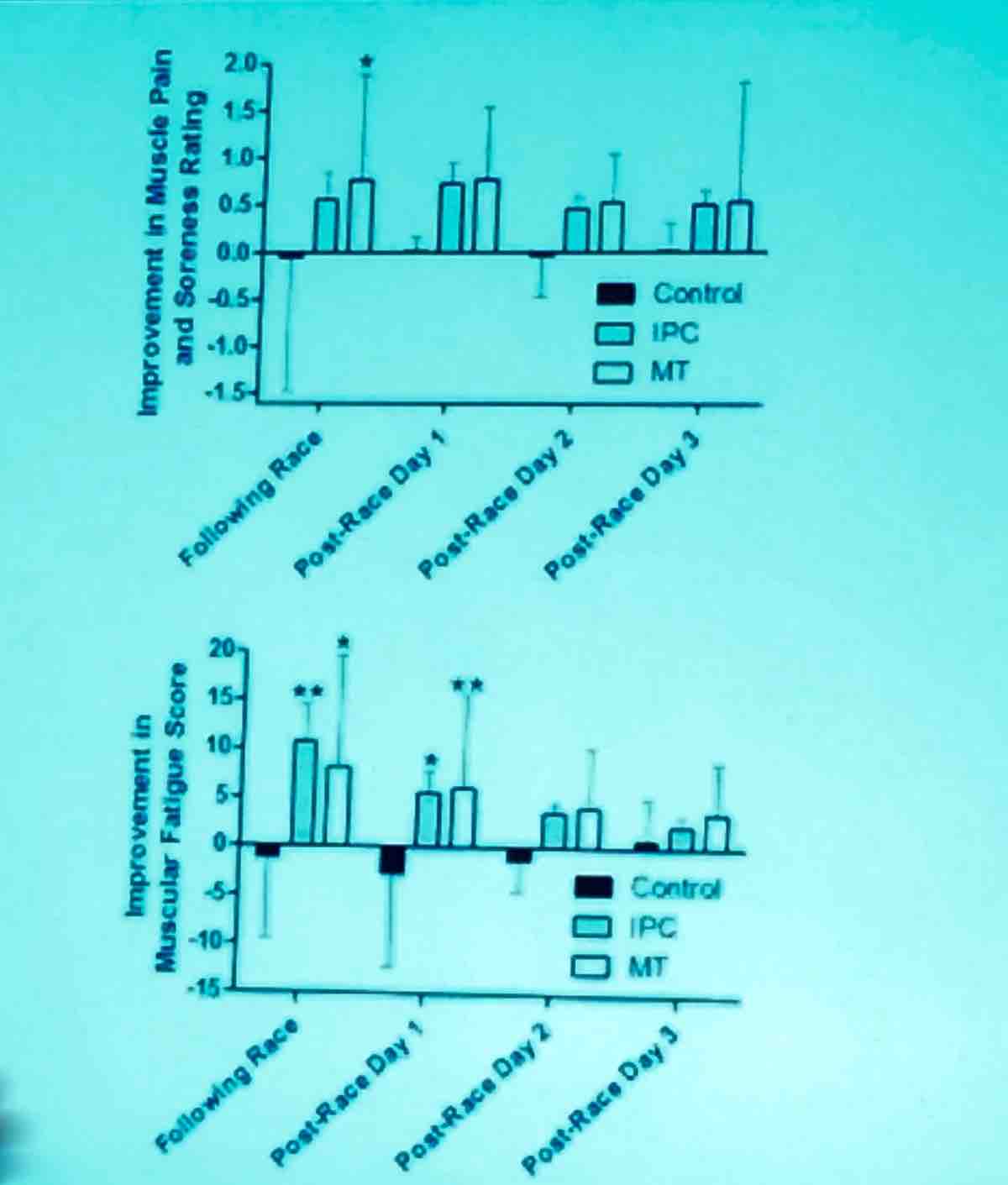

A 2015 Western States research project looked at massage versus intermittent pneumatic compression (IPC) versus a control (supine rest): The only statistical effect was immediate post-treatment. For both post-race massage and IPC, there was immediate subjective benefit, but no long-term benefit. This study was then taken to the 2016 Tarawera Ultramarathon where runners received massage versus IPC versus a control (again supine rest) immediately post-race and at post-race days one, two, and three. There was immediate subjective benefit immediately post-race and post-race day one but no statistically significant sustained benefit for either intervention versus a control.

[Author’s Note: There was no statistically significant benefit, but given the small numbers included in the study, they may not have had the power to detect a benefit of massage or IPC, which would be a type II statistical error. See the slide below for further clarification and note the large overlapping confidence intervals.]

Cardiac Mechanics and Health in Ultra-Endurance Athletes

Thijs Eijsvogels, PhD is a post-doc in the Department of Phsyiomics at Rabdoud University, Netherlands

Dr. Eijsvogels started with the statement: “We are all aware that exercise is very good for you, especially for your cardiovascular health.” It initially became widely accepted that physical activity was good for the heart in 1953 when Professor Jeremy N. Morris, a British epidemiologist, found there was a lower incidence of heart attacks in more active vocations, such as conductors and postmen compared with bus drivers. His studies marked the start of the modern promotion of exercise for heart health. His findings have, of course, been supported by numerous studies since.

[Author’s Note: Please see my previous coverage of Aaron Baggish’s talk at the 2014 American College of Sports Medicine for iRunFar.]

Current recommendations are that we should exercise 150 minutes per week at moderate intensity or 75 minutes per week at vigorous intensity.

But does longer-distance running or “excessive exercise” put us at increased risk of cardiac disease? He discussed each of the following:

- Sudden cardiac death: Aaron Baggish led a study including 11 million athletes running full and half marathons. There were 59 total cases of cardiac arrest. The risk of this happening was higher in marathons (1.01/100,000) than half marathons (0.27/100,000). The most common causes were hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, which is congenital, myocardial infarction (MI), due to coronary artery disease, and arrhythmias. It seems these pre-existing abnormalities of the heart can become unmasked and problematic in long-distance strenuous runs.

- Cardiac hypertrophy in athletes: The heart of an athlete is bigger. We believe this is a benign physiological adaptation to exercise.

- Cardiac biomarker release: Cardiac troponins, which are enzymes released during damage to the heart muscle, have been found to be increased to the cutoff level used to diagnose MI in 50% of marathon finishers. The magnitude of the increase depends on the intensity of the exercise. But there is a very quick return to baseline in an athlete (24 hours) versus in an MI (six days). “I think this is very strong evidence that the pathophysiology of the troponin release is different in athletes.” [Author’s Note: There was dissent from the audience to this comment and the participant said that we need more long-term (decades-long) studies following athletes with high post-race troponin levels to know this for certain. Thus far there have been no correlations found with increased cardiac markers post-race and cardiac arrest, albeit in shorter-term studies.]

- Arrhythmias: There was a very famous study of cross-country skiers in Sweden by Andersen K., et al. showing a higher risk of developing arrhythmias (particularly atrial fibrillation) in skiers versus controls. The risk of developing an arrhythmia at some point in the life of a skier is increased the more intense the racing history and the more racing over the course of a lifetime. [Author’s Note: This study was of men only.]

- The risk of heart disease with endurance exercise: First, he did a good job debunking the study that has been all over social media (Schnohr, P., O’Keefe, J.E., Marott, J.L., Lange, P., Jensen, G.B. (2015). Dose of jogging and long-term mortality: the Copenhagen city heart), which found an increased risk heart disease with the highest level of aerobic exercise reported. This study’s finding was based on only two subjects, in which the cause of death was unknown. Thus, the conclusion was drawn from far-from-sufficient data.

He then went on to discuss a large German study of men only >50 years old (Möhlenkamp S, et al. Eur Heart J , 2008, vol. 29 (pg. 1903-1910)), which found an increased prevalence of calcium in the coronary arteries of runners versus controls. However, a new Dutch study by the speaker, which has been accepted to the journal Circulation, but not yet published, clarifies that runners tend to have calcified rather than mixed plaques and calcified plaques have the lowest risk of rupture which the speaker interprets to mean older male runners have a lower risk of cardiovascular events than controls. Finally, he mentioned there appears to be an increased risk of myocardial fibrosis (myocardial fibrosis is an increase in the collagen [or connective tissue] in the heart which can result in a stiffening of the heart and potentially an irregularity in its pumping pattern/ability) in runners, however the fibrosis occurs in atypical locations (septum or right-ventricle insertion site) and the cases he presented were anecdotal and thus the true prevalence of myocardial fibrosis among runners is not known and therefore can not yet be compared to non-runners. The significance of this fibrosis seen in endurance runners is not currently known and is something endurance-sports researchers are attempting to understand.

In conclusion, the health benefits of running are largely independent of running dose and frequency. There is currently no solid evidence of increased cardiac-mortality risk at even the highest doses of aerobic exercise.

Blister Prevention and Management

Brian Krabak, MD, MBA, FACSM, Clinical Professor, Rehabilitation, Orthopaedics and Sports Medicine, University of Washington and Seattle Children’s Sports Medicine

As opposed to shorter races, blisters are the major reason for racers to visit medical tents.

- Antiperspirants/lubricants work but only for an hour and then there is rebound increased friction.

- Taping pre-race in places of most frequent blistering can be highly effective for preventing blisters, as demonstrated in the 2016 study by Grant Lipman where they applied paper tape to frequently blistered areas pre-race. See the excellent New York Times article about the study.

- Over years of training, skin adapts to prevent blisters.

- Shoe inserts can be helpful in dissipating sheer forces.

- Wear moisture-wicking running socks.

Exercise-Associated Muscle Cramping in Endurance Athletes

Martin Schwellnus, MBBCh, MSc (Med), MD, FACSM, FFIMS, Professor of Sport and Exercise Medicine, University of Pretoria, South Africa

Exercise-associated muscle cramping (EAMC) is a syndrome and not a diagnosis. EAMC is more common the longer the duration of the sporting activity. The prevalence is highest in triathletes (78% over the course of a lifetime).

EAMC can be due to a primary cause—the exercise itself–and/or secondary causes like muscle injury, illnesses (motor-neuron diseases, Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, for example), and medications (he did not list any in particular).

Cramping is not caused by dehydration or altered blood electrolytes. He listed five reviews from 2009, 2013, 2014, 2016, and 2016 that all do not support the dehydration/electrolyte theory of cramping.

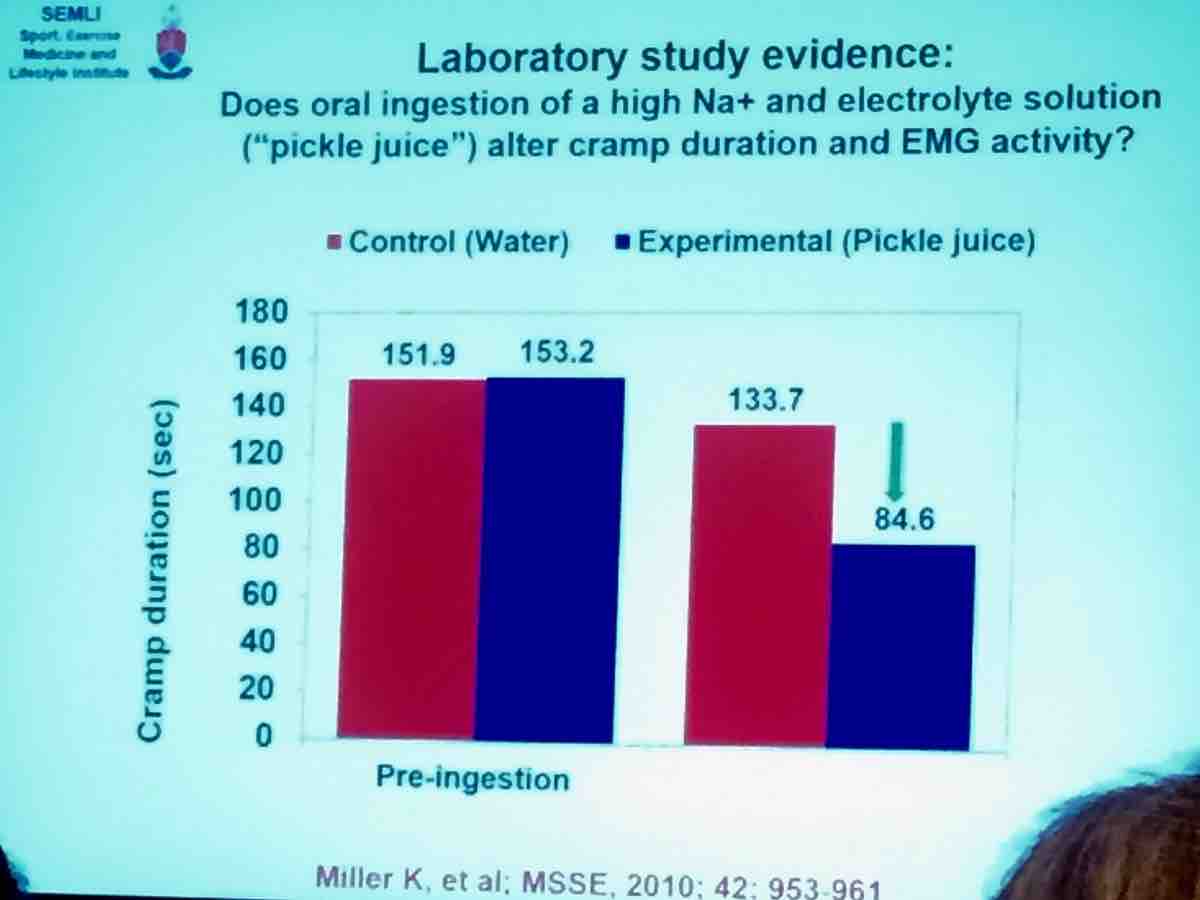

Advanced age and faster running pace as well as previous cramping increase odds of cramping. Cramping is a neurally mediated reflex. Drinking pickle juice can immediately stop cramping before it has time to alter the osmolality of the blood, which provides more evidence that cramping is neurally mediated (rather than by electrolytes or hydration) via mouth and gastrointenstinal nociceptors. Nociceptors are a special type of sensory neuron that cause us to sense potentially damaging/noxious stimuli as painful or uncomfortable.

A prospective cohort study from 2011 by Schwellnus M., et al. found increased speed of racing and pre-race muscle damage as risk factors for the development of muscle cramps in a 56-kilometer race.

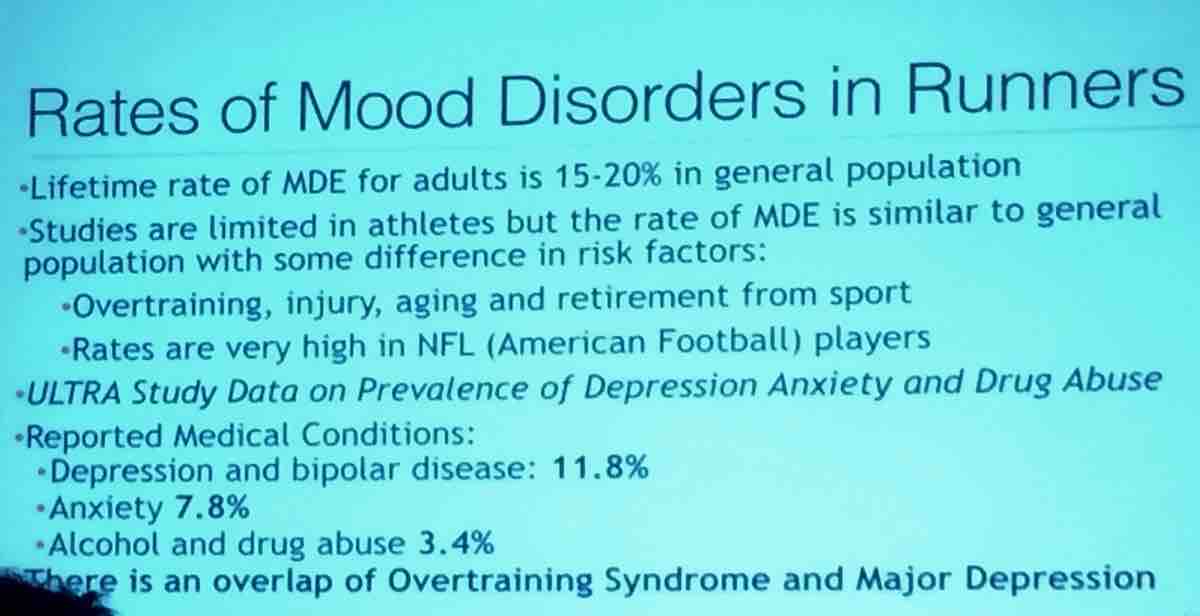

Psychological Health and the Ultra-Endurance Athlete

John Onate, MD, Associate Professor, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, University of California Davis

Major depression causes increased all-cause mortality and increased risk of heart disease, diabetes, and high blood pressure. Our brain is not a separate entity from the rest of our physical body and you cannot look at the other organs on their own, separately from the brain.

When it comes to treating endurance athletes, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) are generally better than tricyclic antidepressants (TCA). SSRIs have less side effects that TCAs, which can cause dry mouth, blurry vision, constipation, and, particularly importantly for runners, increased core body temperature. Nortriptyline (a TCA) has significant cardiac side effects–for medical folks out there, prolongation of the QTc interval, for non-medical folks, a small risk of a potentially fatal irregular heart rate–and would be a more concerning medication to take during training/racing.

[Author’s Note: I asked John personally what he would prescribe first to his ultrarunner patients and he said “Celexa”, a SSRI, followed by Wellbutrin, which is considered an norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake inhibitor. He counsels his patients to stay on their meds during multi-day races.]

Thirty to forty minutes of moderate exercise at least four days a week for two to three months is effective as an antidepressant. Patients who are elderly and/or have cardiovascular disease may benefit even more. Exercise is also effective for bipolar disorder, anxiety, and substance abuse. He then went on to explain that there is research going on to understand the biochemical reason exercise is a potent anti-depressant and anti-anxiety treatment and mentioned the activation of serotonin receptors in the brain and release of the protein adiponectin.

The bottom lines of this talk were that:

- Ultramarathon runners may have a higher prevalence of certain mental health disorders such as depression and bipolar disorder, though only one study has been done to investigate this.

- Exercise can be an effective treatment for certain mental-health disorders such as depression, bipolar disorder, anxiety, and substance abuse.

[Author’s Note: Readers should not expect that exercise will be sufficient to adequately treat mental-health diseases. If you have a diagnosis or believe you have a diagnosis of a mental-health illness, you should seek help and consult a psychiatrist about proper medication and treatment. You can take into consideration and discuss with your doctor the medications preferred by Dr. Onate above. For additional reading, please see Rob Krar and Nikki Kimball’s open discussion of their own experiences with depression.]

Call for Comments (from Meghan)

What are your thoughts on some of these new research findings on ultramarathon runners?