[Editor’s Note: This is the first in a two-part series about racing the Western States 100. This Part One is about the race’s challenges, while Part Two is about conquering those challenges. Part Three provides fresh advice for modern racing.]

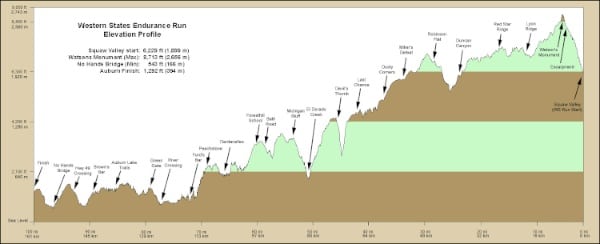

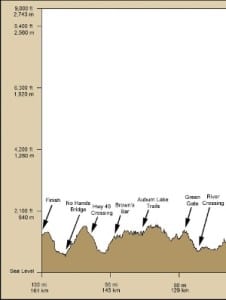

To a logical observer, it seems simple, if not easy, as 100 milers go. A race that features, in the second half:

- A final 40 miles of buttery singletrack and road;

- A gentle, low-altitude downslope punctuated by only a handful of climbs;

- As much crew and spectator access as a road marathon; and

- More food and libations than a summer carnival, and more ice vendors and wading pools than a Holiday Inn.

How, then, can such a smooth, shaded, well-groomed, well-stocked, spectator-laden event create so many blown quads, busted toenails, blistered feet, bloated bellies, and beleaguered bodies than any other race on the planet?

Indeed, I’ve asked myself that question many times over, as I’ve been on both sides of the Western States story: a fortuitous finisher and a disillusioned DNF-er.

In advance of its 41st running, I have spoken with several of the race’s greatest finishers about what makes Western States–on paper one of the easiest 100 milers in the sport–a shatterer of dreams. Bruce LaBelle, an 11-time finisher and perpetual student of the sport, echoed this sentiment when I ran into him at an aid station midway through last month’s Western States Memorial Weekend Training Runs Training Camp run, “On paper, there should be 20 or more guys running 16 hours, but there aren’t. The second half is so runnable, yet the bulk of them have nothing left once they get there.”

Just why this is so can be explained by a several factors–physical and mental–that, in the right combination, produce explosive results.

There’s beauty in the simplicity of the formula: of terrain, elements, competition, hype, and decision-making that coalesce to either create victorious triumph or utter devastation.

Legendary 14-time champion and two-time non-finisher Ann Trason, the ultimate cougar tamer, does not mince words when describing the perils awaiting aggressive runners, “If you fight this course, it will eat you alive.” No race consumes its prey quite like the ‘Western States Killing Machine.’

Several factors–pre-race and mid-race, internal and external, physiological and environmental–combine to produce challenging conditions and situations unique to this event. These conditions and the recipe for destruction are described here.

Mental Factors

Buckles, Top 10s, and Cougars, Oh My! The HYPE.

Western States is the oldest, most historic, and regarded as the most prestigious 100-mile ultramarathon in the world. Its weight–only magnified by the field limit and less than 10% chance at gaining entry–creates considerable pressure for runners to bring their best on race day. Each runner seeks to measure up against not only the best runners in the world, but also the best in history.

Beyond simply finishing 100 miles, adding to the hype value are two additional standards.

The silver buckle, a prize based on that given to horse riders in the original The Tevis Cup, is awarded to those who finish within 24 hours. It represents a level of 100-mile mastery that is among the most sought-after standards in the sport. Markers at each aid station indicate time standards not only for 30-hour finishing cutoffs but also for how to finish under that special one-day barrier.

For elite runners is the top-10 finisher standard. While some races bestow prestige to the top-three podium finishers, Western States is among the few (if not the first) to recognize the top 10. The real prize of a top-10 finish is an automatic entry into next year’s race with the added prestige of a ‘M’ or ‘F’ bib number.

But nothing trumps the hype and prestige of a Western States victory. Etching one’s name on the Wendell Robie trophy secures one’s place among the best ultrarunners in history. Beyond that, securing a cougar trophy at Western States has now become symbolic of–if not instrumental in–propelling a runner to professional status.

Hyper-Preparedness

Western States is by no means the toughest 100-mile race. Only a couple hundred miles south (Badwater Ultramarathon) or southeast (Hardrock 100) will land you at races that are hotter, higher, and tougher than anything most humans will ever come across. Yet, since Western States is best known among all runners, it tends to draw more inexperienced, novice trail runners to its starting line as a bucket-list experience.

This combination of the demands of high-country mountain running, racer inexperience, and pressure to ‘nail it on the first try’ often results in significant over-preparedness, both physically and mentally. First-time or relatively inexperienced runners frequently over-train in their attempts to prepare for the distance, hills, and heat. More is better, until it isn’t.

Mentally, the enormity of 100 miles pushes runners to over-analyze every minutia of the event: shoes, clothes, gear, hydration, nutrition, salt, and crew support.

Because of this, many runners come into the event prepared but physically and mentally exhausted at the precise moment when that demand is highest.

Mountain Mania and Panic!

Indeed, for many runners, Western States may be some runners’ first-ever run in high-alpine wilderness terrain. Moreover, the legendary quadfecta of deep canyons–and generous race-day heat–of the Western States course can also create considerable anxiety among runners. The variety of these conditions unique to this race create logistical challenges that play on the minds of all runners, creating trepidation above and beyond the enormity of 100 miles on foot, even before the race begins.

Once the race begins, few things are certain, but one of them is that you will have problems. If those issues aren’t created by the course through stubbed toes, scraped knees, or sore legs, the brain can create them through bonking, cramping, or extreme fatigue as our Central Governors try to protect us from self-destruction.

Rookie runners, who are often well-prepared instrumentally, tend to be under-prepared for the mental challenges of the issues that befall them, and they tend to react in kind with a loss of cool and, at times, outright panic.

Just how we deal with these issues can make the difference between survival and success, and damage and despair.

The Start Line

There’s nothing like the start line at Western States. Few other major ultramarathons feature such a majestic view: the grand starting arch framing enormous mountains that await runners on race day. Moreover, unique to Western States is that the bulk of runners spend at least a day or two in the immediate vicinity and dangerously close to the frenetic energy of Saturday morning.

In the pre-dawn darkness of race day, the atmosphere is akin to the NBA Finals: the house lights are out and the spotlights shine on the 400-odd runners on the dance floor. Around them are triple the race officials and spectators awaiting the blast of Dr. Lind’s shotgun.

These mental factors create a considerable strain on the organ system that is most vital to survival and success at Western States: the brain.

Physical Factors

Altitude

The high-country altitude–averaging over 7,000 feet above sea level–exacts a significant physiological demand on runners in the critical opening third of the race.

For most high-country 100 milers with marked, persistent high altitude such as Hardrock or Leadville (each well over 10,000 feet for the bulk of the race), most runners will prepare either with a week or more acclimatization at altitude, or do so artificially using altitude tents at home in the weeks (or months) preceding the race.

However, since the bulk of Western States is sub-alpine and the opening third of the course is off limits to runners each spring due to snow cover, the demands of the high-country segment are frequently underestimated. Moreover, the majority of the race’s biggest names including multi-time champions and course-record holders such as Jim King, Ann Trason, Tom Johnson, Tim Twietmeyer, Mike Morton, and Scott Jurek were flatlanders who never lived at altitude in the days they dominated the race. They and other low-living runners’ success at Western States can downplay the effect that 30-plus miles at 6,500 to 8,500 feet might have on those who are ill prepared or overly aggressive.

The physiological demand of high-altitude running is well understood: the elevation decreases air pressure and with it the partial pressure of oxygen in the air is decreased, making it more difficult for the lungs to obtain oxygen from each breath.

Just how exactly this affects the body is not completely certain. While it is true that, in theory, the lungs have a tougher time extracting oxygen from the air, the bigger effect may be on the brain. Chemoreceptors in the lungs and blood vessels alert the brain to the relative oxygen concentration. If deemed too low, the brain will respond by increasing both breathing rate and heart rate. Any increase in heart rate has these potential effects: a change in fuel utilization during exercise, shifting away from fat burning and toward the use of precious glycogen stores, and a negative impact on the Central Governor.

The Opening Climb and Ridgeline Terrain

Many races begin with an uphill, but few match that of Western States. While Rocky Mountain region residents might scoff at the height of Squaw Valley, the race begins by literally running up a mountain–4.5 miles and over 2,500 feet of gain, to be precise.

Such a climb may seem minor by some standards, but that it occurs at the very beginning of the race–when hype and adrenaline are redlining and at a starting altitude of 6,250 feet–creates the perfect conditions to light the fuse of the anaerobic bomb. LaBelle points out, “Everyone goes too fast up the first climb–adrenaline, getting pulled along with peers, and a mostly runnable grade.” The latter is in part because runners are on a smooth gravel road for nearly the entire ascent.

When runners arrive at Emigrant Pass at 8,750 feet, it is technically ‘all downhill from there.’ But the course hardly gets easier. LaBelle points out that the course drops close to 2,000 feet–with scores of short-but-strenuous climbs–in the next five miles over rugged terrain marked by big boulders, countless marble-y rocks, and washouts from the many snowmelt creeks that beset the Granite Chief Wilderness.

Indeed, the entirety of the first 30 miles consists of rocky, undulating, ridgeline trail that, as LaBelle says, “roll[s] along between 6,800 and 7,200 feet, adrenaline flowing, is not a good way to prepare for the later sections of the race.”

In short, aggressive high-country running can turn the first 50 kilometers of the race into a literal anaerobic-threshold run: of runners spending many miles, if not hours, at a heart rate commensurate with a half marathon or even 10k-road-race effort. However, because the muscular strain is low and early-race joy is high, the true cost can be difficult to perceive.

Nevertheless, the metabolic consequences are enormous: glycogen stores are incinerated and hypoxic muscle fibers are bathed in acid. The Killing Machine quietly clicks and whirs into action.

The Meat Tenderizer: Punishing Downhills

From the high point at Little Bald Mountain at mile 31, the runners a get much-needed respite from the high altitude as well as the relentless, death-by-1,000-papercuts footing of rocks, roots, sticks, and washouts. Once off the Little Bald switches, runners are rewarded with a softer, smoother dirt trail.

Western States veterans refer to this section, which runs to the bottom of Deadwood Canyon, as ‘the downhill half marathon.’ It, too, is a pivotal section of the course. It can be a place for runners to recover from the high country and regenerate glycogen stores and mental fortitude for the canyons. Or it can be a quiet, destructive force on an already compromised system.

Those who ran the high country too aggressively take metabolically-compromised muscles into a steep downhill section that features roughly 4,000 feet of loss over that section, the bulk of which comes in two concentrated doses: in the two kilometers before Dusty Corners (mile 38) and in four kilometers between Last Chance (mile 43) and the bottom of Deadwood Canyon.

Downhill running exacts a cost on the legs of every runner, but the toll is an order of magnitude larger on metabolically stressed muscle tissue. The reason that runners are frequently more sore after a road marathon versus a trail 50k or 50 mile is not simply because of the unforgiving pavement. It is also because of the metabolic stress that fast road running places on the muscles which are working for two to four hours or more, anaerobically, in addition to the impact stress.

This same effect happens at Western States to those runners who ran too hard in the opening 50k. They take those compromised muscles–already tenderized with a tasty acidic solution–and begin to hammer them with a meat tenderizer.

The Heat! My God, the Heat!

The midday, mid-race heat that is fundamental to the Western States experience exacts both a physical and mental toll on runners. It is well known and accepted that the heat extracts more sweat and water vapor from the body, and makes it more difficult for runners to consume enough fluid to maintain homeostasis for the 100-mile distance.

But perhaps the lesser-known but more impactful effect of high temperatures is on both heart rate and the Central Governor. Increases in core body temperature cause the brain to increase heart rate in an effort to dispense that heat through the skin. And while an increase in core body temperature will shunt more blood away from central organs and tissues and toward cooling surfaces, any increase in heart rate will have a two-pronged effect: changing fuel utilization toward more sugar burning and shunting blood away from the digestive system.

Thus, the stomach can shut down at the precise time when it needs the most exogenous sugar sources: when the muscles are burning through precious glycogen stores. This is ‘the most unkindest cut’ from the blade of Western States heat.

Indeed, the reason many Western States veterans engage in heat training–active exercise or passive exposure to high temperatures in advance of the race–is not only for the adaptive benefits to sweat and electrolyte balance, but for the central effects of decreased heart rate and mental composure that come from being heat trained.

To keep your cool, you have to stay cool. But you also have to keep your mental cool.

The heat is yet another factor that shifts metabolism anaerobic, once again bathing muscle tissues in an inflammatory soup.

The Killing Machine whirs along: baste, hammer, repeat. Baste, hammer, repeat.

Besides quad death, the Killing Machine creates myriad other problems, including:

- Blisters

- Nausea

- Cramping

- Brain Bonks

The former is usually due to a lethal combination of wet feet, shearing of the foot inside the shoe due to over-striding on the prolonged downgrades, and can be worsened by over-hydration. The latter trio of heat, altitude, and high-heart-rate-induced Central Governor effects are intended to slow down and protect a runner and his or her compromised internal organs, muscles, and brain.

The Canyon Fartlek

If runners make it to the bottom of Deadwood Canyon (mile 45) in one piece, they’re in a great position, but in no means out of danger. Now begins a critical physiological challenge: climbing in and out of the canyons. Western States features four significant river canyons: concentrated descents of 1,500 feet or more and then an immediate climb of the roughly the same height.

Even conservative runners who budget their energy and legs well in the high country will, after 13 miles of easy running at an aerobic effort, feel the shock of the immense effort of climbing 1,700 feet in 1.5 miles to the Devil’s Thumb Aid Station. Even with a leisurely hike, most runners are thrust into an anaerobic state magnified by the midday heat that is most pronounced in the canyon bottoms.

The course from Last Chance to Foresthill is this pattern, in triplicate: pounding downhills followed by air-sucking, heart-pounding, broiling climbs. The result is a punishing fartlek workout with strain on both canyon walls.

Hammer, baste, repeat. Hammer, baste repeat.

Successful navigation of the canyons requires mitigating the hammering of the downhill section as well as tiptoeing the red line of anaerobic burn on the ups.

The most successful and often fastest runners of the day are those who can efficiently float the steep canyon descents, then with equal finesse float in and out of the high-intensity anaerobic zone on the climbs. They know precisely how to throttle up and down without jeopardizing the steady flow of glycogen to the brain or blood flow to the stomach. Meanwhile, they mitigate temperature fluctuations using external cooling and they keep a steady stream of water, calories, and modest electrolytes going in to maintain homeostasis.

It is a precarious balancing act on the high trapeze.

Pacer Mania and the Cal Street Speed Trap

Runners who successfully navigate the treacherous high country and canyon sections to reach Foresthill at mile 62 are justly rewarded: a raucous, supportive crowd; smooth, runnable, and fast terrain; and the assistance of a pacer.

Every Western States veteran I spoke to notes the importance of this section, namely of California Street–the section of trail that begins just west of town, that takes the runners on a gentle, fast descent to the American River. They all note Cal Street as a pivotal section where aggressive running and preservation must be delicately balanced. Yet not a single one of them believes that the race is won–or even truly begins–at this point. A pacer can be vital in this section, but can also greatly threaten that balance.

Pacers were originally instituted into Western States as a safety precaution, as the bulk of runners competing in the early years, including the winners, took close to 24 hours to finish. Pacers were intended as safety measures to prevent mishaps that may arise from extreme fatigue and running in the darkness. Today, for most runners, the real benefit of pacers is psychological and performance enhancing: a pacer can provide another brain and another voice to keep the runner moving quickly and effectively in the remaining 38 miles.

The pacer, while enormously helpful, can also be a double-edged sword of enthusiasm and overzealousness.

Pacers are typically other ultramarathon (or road-marathon) runners, and they bring a useful combination of fitness, energy, and competitiveness to the day. But that combination–often stoked by watching the competition unfold all day, anxiously awaiting their chance to run–can push an already-taxed runner over the edge, often inexorably.

Whether from direct pacer pressure or simply the circumstance of running with another person, ‘pacer mania’ and overly aggressive Cal Street running is a common yet often overlooked occurrence in the later stages of the race. Notable instances are abound on the elite men’s side in recent history, where fast-running men have pushed too hard either in the lead or in pursuit of it only to fall precipitously over the final miles.

This includes in 2011 when a hard-charging Nick Clark opened a several-minute lead over Kilian Jornet on Cal Street, only to give it all back as well as second place to Mike Wolfe in the last 15 miles. The same fate befell Ryan Sandes a year later when he and pacer Phil Villeneuve surged past Timothy Olson just past Dardanelles (mile 66). Olson, no doubt benefiting from his wiser, more level-headed pacer in Hal Koerner (with two cougar trophies of his own), was unmoved and stayed the course. Olson chipped away at Sandes’s lead, drawing even just before the Rucky Chucky River Crossing at mile 78. Then, once across the river, Olson surged, putting nearly a minute per mile on Sandes in the final 20.

Before that, in 2010, co-leaders Anton Krupicka (with pacer Joe Grant) and Kilian Jornet (with Rickey Gates) went to war on a brutally hot Cal Street, while Geoff Roes–then a distant third–backed off the pace he called “unsustainable.” J.B. Benna’s Unbreakable documented the battle and resulting carnage. Between miles 80 and 90, Krupicka faded while Jornet spent nearly an hour sitting: on a blanket at Green Gate, beside a creek, and then in a chair at Auburn Lake Trails Aid Station. This opened the door for a perfectly executed surge by Geoff and the most epic come-from-behind victory since Jim Howard’s sprint past Jim King in the final mile of the 1983 race.

Perhaps the most striking implosion in race history took place in 2006. On a brutally hot year, Brian Morrison came into Foresthill in the top 10 where his pacer, seven-time defending champion Scott Jurek, was waiting to run him to the finish line in Auburn. In his autobiography Eat & Run, Jurek describes that day, recalling that he told Morrison, “By the time we reach the river, you’re going to be leading.”

In the heat of a biblically hot day, they pushed hard along Cal Street, and, true to form, Jurek led Morrison across the river in the lead. Morrison was running strong and built a sizeable lead over the last 20 miles. But as Morrison and Jurek entered Auburn’s city limits, things began to unravel. At what should’ve been his crowning moment, Morrison swooned. He collapsed on the track a mere 300 yards from the finish. With help, he got to his feet and shuffled to the home stretch, only to collapse again. He finally crossed the finish line with plenty of time to spare. Since he received physical aid from Jurek and his crew, Morrison was disqualified was logged as a DNF as he failed to finish under his own power, and the win was awarded to second-place finisher Graham Cooper. [Editor’s Note: Thanks to the esteemed Tropical John Medinger for the clarification.] This remains the most controversial–and clearly disappointing–finish in race history. Whether or not Jurek pushed Morrison too hard is up for debate. But the fact remains: Morrison pushed too hard and, tragically, came up empty with only a precious meters to go.

In each instance, pacer-clad runners pushed too aggressively on Cal Street, only to pay for it later. While the section of the course is fast and runnable, for every minute pushed too hard and too anaerobic, it may cost a runner two-, three-, or even five-fold over the last 20 miles.

Obscured somewhat in the acrid dust of that historically hot day in 2006 was the other-worldly performance of Tim Twietmeyer who quietly and methodically as always notched his 25th (and final) Western States finish, and his 15th top-10 finish–two feats that will likely never be equaled. Indeed, Twietmeyer knew things that Morrison–and perhaps even Jurek–did not.

What are those things? Besides an implicit understanding of running with the course instead of against it (which will be outlined in Part Two), Twietmeyer recognized that, on Cal Street, fast but conservative running is crucial. While the 16-mile stretch is mostly smooth downhill, it is punctuated by 15 boiling, exposed, gut-busting rolling climbs between Dardanelles (mile 66) and Peachstone (mile 70) aid stations, a truly nauseating dirt-road climb that’s appropriately named ‘Six-Minute Hill’ at mile 72, and a handful more sandy, scorching, sunbaked rollers en route to the river crossing at mile 78.

Tantalizing Simplicity: The River to the Finish

Once at the river and up to Green Gate Aid Station at mile 80, it is truly smooth sailing. Easy running, in fact. Twenty miles and a pair of significant but rather benign climbs separate runners from the final 250 meters of triumphant track at Placer High School.

That those final miles, the last 20% of the race, are so simple and straightforward adds to the enormous power of the Killing Machine: that it needs only 80 miles to lay complete waste to most runners. It’s notable that the most remote aid station with the most dropouts is Auburn Lake Trails. It is said that A.L.T. has as many cots as a M.A.S.H. unit, with equal carnage. At mile 85.5, it is a classic flame-out spot for runners who manage to make it out of the canyons, but who are reduced to a hobble a few miles past the American River before tapping out.

*****

There’s immense beauty in its simple brutality.

Take the granddaddy of all 100 milers, add enormous hype and expectation, and a sprinkle of physical and mental fatigue. With pre-race nerves redlining, fire the gun, and shoot up a 2,500-foot ascent to kick off a rugged, rolling 50k at high altitude. Then, just as you’re just about beaten senseless, it lets go of the leash: a dozen-mile reprieve, just enough to develop a false sense of security that only serves to set the hook. Then it’s the triple-double of canyon downs and ups, bathed in oppressive heat. Just as you’re coming up for air, it throws excitable crowds and an overzealous pacer with whom you’re thrust into a wide-open, sundrenched trail that bottles up the heat well into the night.

By sunset, the Killing Machine has run its course: taking the wristbands and races of roughly a quarter (and up to half) of those who started in Squaw Valley at sunrise. Those it spares to continue are often left hobbled and limping, reduced to a hike to the finish line.

A precious few survive the trials, avoiding the clicking and whirring, minimizing the basting and hammering. It’s no coincidence that these precious few have cornered the market on silver buckles, top-10 finishes, and cougar trophies over the past four decades.

In Part II, these cougar tamers will share their wisdom, insights, and secrets to surviving and thriving amidst the Western States Killing Machine.

Call for Comments (from Meghan)

- There are thousands of you who have raced Western States, and a good chunk of you who have fallen victim to one or more of the course’s complexities. Tell us, what was the hardest part of the course? Where did you make the most mistakes? What did you learn from your experience(s)?

- Also, there are a select, small group of you who’ve had miraculous success at States. How? Where? In what ways did you avoid falling victim to the Killing Machine?